On the desk in my home study sit several objects that point to various aspects of my journey of faith. There is an icon depicting the raising of Lazarus, a Pope Francis action figure, a wooden cross handed down to me from my grandfather, and a small statue of a bespectacled man wearing a Franciscan habit.

The cross reminds me of the faith of my parents, grandparents, and ancestors. The smiling pope waves at me as I write and read, reminding me how his election and pontificate inspire my own ministry as a pastoral minister, theologian, and preacher. The image of Lazarus emerging from the tomb, wrapped in burial clothes with Jesus and a crowd of witnesses looking on, reminds me of the many resurrections I’ve experienced in 43 years of life and the grace contained in each of those resurrections.

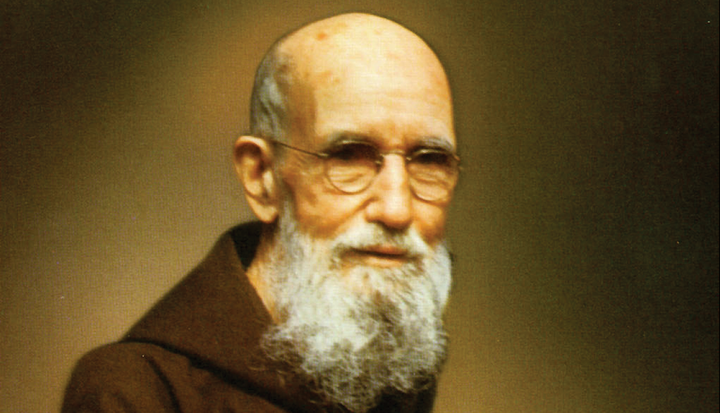

The little friar who stands next to my pencil cup is Father Solanus Casey, now known as Blessed Solanus Casey, a Capuchin-Franciscan friar of the Detroit province of Capuchins who was beatified in November 2017. The statue is a replica of a life-sized work carved by an Italian artist that greets visitors to the Solanus Casey Center in Detroit. It reminds me of my own connection to Detroit, the Capuchins, and my ongoing call to ministry rooted in the Franciscan charism.

In the mid-1990s, following graduation from high school, I began a serious period of discernment. I had sensed a call to the priesthood since I was a child. That call remained and seemed to grow as I entered early adulthood. I spent time discerning with my home archdiocese in Milwaukee; the Diocese of Green Bay to the north of my home in Fond du Lac, Wisconsin; and the Capuchins. I knew the Capuchins well, having attended their high school seminary, St. Lawrence.

I first encountered Solanus Casey during a vocations retreat at St. Bonaventure Monastery in Detroit. The cause for his canonization was well underway—he had just been granted the status of venerable by Pope John Paul II. However, few Capuchins boasted or told me the story of the man who laid buried in the wooden casket outside of the chapel, at least not during my first visit. I noted the many pieces of paper that laid on top of the simple tomb, scribbled requests for Solanus’ intercession for healing. I joined many people from Detroit who filled the monastery chapel on a Wednesday afternoon for a Blessing of the Sick service, a weekly tradition dating back more than 100 years. For many of those years, Solanus was part of the service himself, and he continues to be a part of the ritual as pilgrims pray for his intercession.

Solanus spent most of his life of priestly ministry as a porter at St. Bonaventure and at Capuchin friaries in New York and Indiana. This brought him in contact with many people coming to the door seeking food, financial assistance, and healing from illnesses. While in Detroit during the Great Depression he cofounded what is now known as the Capuchin Soup Kitchen, which provides hearty meals for the poor. He kept a notebook of those whose infirmities were cured or life circumstances improved, not because of his intervention—he was far too humble to assert that—but because they had enrolled in the Seraphic Mass Association, a Capuchin organization that helps fund foreign missions and offers prayers for its members. His notes included many such miracles or what Solanus called “favors”—tumors disappeared, diabetes cured, suicides averted, jobs found, housing secured, alcoholism in remission.

With humility being one of the hallmark charisms of the Capuchins, a charism Solanus himself modeled throughout his life, it was clear that I would need to ask more questions and enter into conversation with the friars about Solanus. The friars, some of whom worked closely with him, shared stories and memories from his life and the time following his death. I was drawn to Solanus’ ongoing witness as I grew more and more drawn to the Capuchins.

After several years of discernment and formal candidacy, I joined the order. The first year of formation, postulancy, took me to Brooklyn and St. Michael’s Friary, another place where Solanus lived and served.

Like me, Solanus discerned the diocesan priesthood in Milwaukee. However, he was turned away because those considering his application were concerned about his academic ability and his difficulty in grasping German. He was encouraged to consider a religious order instead. The German-speaking Capuchins were also concerned about the language issue and decided to ordain Solanus a “simplex priest.” This allowed him to say Mass and minister, but he could not hear confessions or preach doctrinal sermons. The restrictions were never lifted, and Solanus accepted them as his vow of obedience required. He focused his ministry on reaching the people who came to the monastery door seeking help. Thousands of lives, if not more, were changed for the better as a result of his ministry of presence, a ministry that continues to this day through the Capuchins in Detroit and elsewhere and through Solanus’ ongoing intercession.

I left the Capuchins during my postulancy year. Looking back it was the right decision, but remains one of my greatest regrets in life. It was the right decision because I, unlike Solanus, have never been very good at obedience, and I certainly wasn’t in my early 20s. Yet now I find myself most days being challenged by obedience, accepting sections of canon law—and interpretations of that law—that limit the scope of my ministry to the people of God as a formed and experienced preacher. I preach when I am invited, but not in the context of the Sunday Eucharist, because I am not ordained. When that reality frustrates me I think of Solanus, our shared limits in ministry, and the many ways in which I, too, am called to a ministry of presence.

This leads to one more way in which Solanus’ life and ministry connect to my own. I now serve on the staff of Lumen Christi Catholic Community in St. Paul, Minnesota. Lumen Christi is the result of the merger of three neighboring parishes. One of those parishes was the Church of St. Therese, whose founding pastor in the 1920s was Father Edward Casey, Solanus’ brother. Many parishioners who were part of the St. Therese community join me in an ongoing appreciation of Solanus’ incredible life and ministry and in prayer for his canonization.

This article also appears in the February 2020 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 85, No. 2, pages 45–46). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Image: Wikimedia Commons

Add comment