Christian hermits, or solitaries as they are sometimes called, have fascinated me for years.

It may simply be that for an introvert like me, living alone with God in a little house in the woods sounds like a dream come true. I have collected memoirs and biographies of all kinds of folks, Christian and not, famous and not, who have lived as hermits for some amount of time. Anthony the Great lived in an abandoned fort for two decades. Catherine of Siena locked herself in a closet for three years. Thomas Merton lived in a hermitage in his last years but was a very social hermit, welcoming many visitors and guests.

There are other less famous solitaries—Karen Karper Fredette, W. Paul Jones, Maggie Ross, Barbara Erakko Taylor, Sara Maitland, and others—who have written memoirs I have gobbled up about their ups and downs living an eremitic life. But why do I do this? I have family and work commitments. I am not moving to a cabin in the wilderness anytime soon (what about Wi-Fi?). What am I seeking?

When I came across the life of Charles de Foucauld, a hermit, at least part-time, for much of his life, I fell in love with him (don’t tell my husband) as many have and began to discover some of the answers. Or at least, a new question.

Charles was born in France in 1858. After a dissolute young adulthood he had a conversion experience and became a priest and missionary, making his home, finally, in Algeria around the turn of the 20th century.

Like Francis of Assisi, he had a deep love of solitude as well as a deep love of neighbor. Charles spent his solitude in prayer and long walks as well as in the study of scripture and local languages, especially Tuareg. (He wrote a Tuareg/French dictionary, still widely respected.) He also poured himself out for others: He talked to all kinds of people; he cooked and did laundry for his neighbors; he gave away alms, food, and medicine; and he bought people out of slavery.

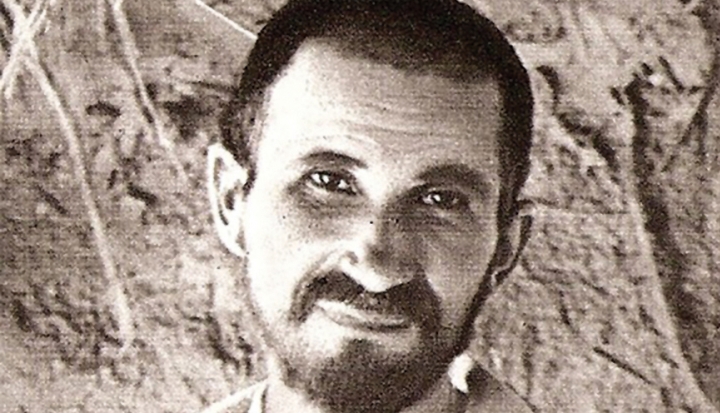

In photos at this time in his life, Brother Charles is gaunt, bearded, and with eyes so bright and open that you can almost see right into his great, warm heart. In fact, he wore a white robe with the Sacred Heart etched by hand on his chest. It was not his heart alone, but Christ’s, that was full to overflowing.

Charles could not sustain his love of neighbor without solitude. He wrote, “One must go through the desert and sojourn there, to receive God’s grace. . . . In this solitude, in this desert life, alone with God, . . . God gives Himself to him totally, if he in his turn will give himself totally to God.” In the last decade of his life, he built a remote hermitage—several days walk from his home in the already remote village of Tamanrasset—high in the Ahoggar Mountains. In photos it looks simple but elegant, built of many multicolored stones, high on a windswept plateau. I can only imagine the awe and peace in God Charles must’ve felt when he was there.

Perhaps because he was so deeply connected to God’s love through his pursuit of solitude and prayer, Charles did not approach the native people of Algeria, as many of his European colonial peers did: subjugating, cheating, and abusing them, treating them as pawns or barriers to French military advantage and economic profit. In fact, Charles implored and interceded with local French personnel to treat native peoples with dignity and fairness.

Still, it makes me squirm to read his letters, where he writes of “taming” and delivering Muslims from “spiritual dereliction.” He was a man of his time, believing European culture would save the world. And yet he was critical of French authorities’ treatment of the Berbers and Tuareg tribes, writing that “we know them so little,” and “we do nothing for them.” He sought to convert his neighbors to his Christian faith out of love, not through coercion or shame but through friendship and service. He said, “It is not necessary to teach others, to cure them or to improve them; it is only necessary to live among them, sharing the human condition and being present to them in love.”

In the end, Charles converted and baptized only one Christian: Paul Embarek, whom he had freed from slavery.

In 1916 Charles was accidentally shot by a teenage bandit, with Paul by his side. His ministry may appear a failure, but Charles made an immeasurable impact on the people who knew him. A village woman is said to have remarked, “How terrible it is to think that such a good man will go to hell when he dies because he is not a Muslim!” A local chief and a close friend, Moussa ag Amastan, who had traveled to France with Charles and even met his family, wrote to Charles’s sister: “I cried and shed many tears. . . . Charles, the marabout [holy man] . . . died for all of us too. May God give him mercy and meet with him in Paradise.”

The influence of Charles’s life went beyond North Africa. A group of Christian men and women, moved by his life and teachings, formed the orders of the Little Brothers and Sisters of Jesus in the 1930s and still serve in Algeria, France, and all over the world. In fact, there are now 20 orders, religious and lay, seeking to follow in the footsteps of Charles de Foucauld across the globe. There are many books about his life, including one from a Muslim perspective.

Charles de Foucauld was more than a hermit; he found strength in his times of solitude and prayer to do radical works of love and cross-cultural acts of resistance against the powers and principalities of his time. He loved his neighbor in a way I’m not sure I could. He didn’t want to change people’s minds so much as to be friends with them, cook for them, and live alongside them.

He said, “No matter what is encountered, it is Jesus in every situation.” Charles seemed to reach with ease beyond his own culture and religion to befriend and serve others in Christ; in that ease and love, I find a spiritual model for the multiculturalism and polarization of our own time, especially among Christians, Jews, and Muslims.

Charles teaches me that solitude can be more than rest and escape; it is in fact a spiritual fuel for our love of neighbor as well as our relationship with God. I may not have a cabin in the woods or a stone hermitage on a mountain plateau, but I take some “hermit-time” now and then to rest in prayer with God by myself, which helps me grow in my relationship with Christ, serve others with more energy, and love more fully. As Charles put it, “To receive the grace of God, you must go to the desert and stay awhile.”

Charles’ canonization was approved by Pope Francis on May 3, 2021.

This article also appears in the May 2019 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 84, No. 5, pages 45–46).

Add comment