With the cards, the flowers, the restaurants promoting romantic dinners for two, it can be easy to forget that Valentine’s Day is a saint’s feast day. Instead, six weeks into the new year, Valentine’s Day can often be the stake through the heart of the New Year’s resolutions to eat less candy or get out there and try to meet someone special. If “Saint” is attached to “Valentine’s Day” it is usually in the context of the notorious 1929 Saint Valentine’s Day Massacre, when members of Al Capone’s gang dressed as policemen and murdered seven of their gangland rivals in a Chicago garage. At least St. Patrick has enjoyed the good fortune of keeping his holy moniker attached to the parades, corned beef dinners, and bar specials held in his honor.

While Valentine may get all the love, there are plenty of saints who know from personal experience that love and marriage can be complicated.

The patron saint of difficult in-laws, Adelaide of Italy’s first husband, Lothair, was poisoned by his rival, Berengar. When the widowed Adelaide refused to marry Berengar’s son, she was sent to prison. When Adelaide eventually did remarry, she had to help her second husband put down a rebellion by her stepson. St. Rita of Cascia never wanted to marry, begging her parents to let her join a convent. Instead, her forced marriage to a violent brawler led to the deaths of several of her family members and made Rita the patron saint of loneliness. St. Thomas More’s patronage of unhappy marriages is likely less tied to his own two marriages than More’s involvement in trying to manage the fallout from the unhappy marriage of Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon.

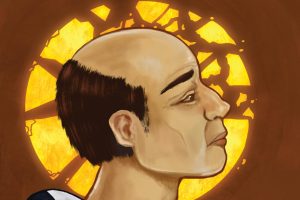

A saint who felt the pain of rejection in a literal and rather dramatic fashion was St. Gangulphus. A powerful eighth-century landowner and aide to French king Pepin the Short, Gangulphus was famous for his piety and charity toward his tenants.

His virtue was rewarded during his lifetime, when he miraculously created a freshwater spring for his household by striking the ground with his sword. He would experience heartbreak, though, when he discovered his wife having an affair with a local priest. Gangulphus exiled the priest, set up his wife with a household of her own, and then retired to another castle to live as a hermit. This fairly merciful solution, though, was not enough. Gangulphus’ wife and the priest broke into his castle and attacked him in his sleep.

They attempted to decapitate Gangulphus, but missed, striking him in the knee. Gangulphus survived long enough to receive his final sacraments before dying of his wounds on May 11, 760. His wife and the priest, who are never given proper names in either the documents adjudicating Gangulphus’ estate or the vitae of the saint, reportedly died of wrenching illnesses soon after fleeing the scene of their crime. For his ordeal, Gangulphus was declared a saint, his relics were translated to and venerated in several churches throughout France and Germany, and he intercedes on behalf of unhappy husbands and sufferers of knee pain.

Thankfully, most unhappy relationships don’t end in betrayal, injury, and eventual death. Many can end when someone is dumped in favor of someone else who is more attractive. St. Helena can relate.

Helena likely grew up in what today is Turkey. She met Constantius, a Roman nobleman and military official, when he was stationed near her hometown. Apparently, he spotted her because she was wearing a silver bracelet identical to his. Considering this a sign, the couple fell in love and had a son, Constantine.

It takes more than matching jewelry, though, to make a relationship work. Once described as “a good stablemaid,” Helena’s very modest family background did not fit with Constantius’ rising political profile; he left Helena for a politically advantageous marriage to his boss’s daughter. Constantine remained close to his mother, and after becoming Roman emperor in 306 made Helena part of his imperial court. As she was a devout Christian, Constantine tasked his mother with travelling to the Holy Land to recover relics from the life of Jesus.

Reports that Helena found the “True Cross” and the nails used in the crucifixion are matters of faith, but she did help repair and preserve two of the earliest sites of Christian veneration: the Church of the Nativity and the Church of Eleona, the site of Jesus’ ascension. Today, Helena’s rejection and late-in-life career renaissance account for her veneration as patroness of divorcees and archaeologists.

Valentine himself might not be that much help for those looking for love. When February 14 was added to the church calendar in the late fifth century, Valentine was described as “justly reverenced among men, but [his] acts are only known to God.” The acts that were attributed to Valentine were healings, not secret Christian weddings, as later thought. In one early story Valentine, identified as an imprisoned bishop awaiting execution, heals his jailer’s blind daughter. In another, Valentine cures a scholar’s son of a “falling sickness,” and converts the boy’s family to Christianity.

The story that Valentine helped Christian couples secretly get married developed more than 1,000 years after his death. During the Middle Ages, people believed that birds mated in mid-February. English poet Geoffrey Chaucer wrote fancifully of a mid-February feast where, under the auspices of St. Valentine, people paired up as well.

So Valentine may help with cataracts and epilepsy, but unless you’re a bird it would probably be best to leave him out of your love life. For those committed to sitting out this commercial celebration of romantic love altogether, there are plenty of saints who have your back. And your knees.

Add comment