The easiest goal to come up with is no goal at all. I can say this confidently, being a lifelong fly-by-the-seat-of-my-pants sort of person. An old boyfriend, Sam, used to cluck disapprovingly at my attitude toward life. “The woman without a plan!” he would hiss at me. So I claimed the title proudly: The Woman Without a Plan. Which is not the same as being without a clue, I want to point out.

Sam had well-developed charts, diagrams, and algorithms for his career trajectory: Ph.D., university tenure, bestsellers, politics, and the presidency were carefully plotted out in a future as concretely and tangibly as if it were a done deal.

Twenty years later, he’s achieved the first two and published several books—not bestsellers, but still. By comparison, without so much as a single Venn diagram for company, I’ve managed to earn a master’s degree. I hasten to add that I’ve written five times as many books as Mr. Focused; but alas, none of mine are bestsellers either. Yet I can’t dismiss Sam’s zeal for his goals. Nor would I write off the possibility that one day an old boyfriend of mine might well occupy the chair in the Oval Office. The smart money is always on The Man With a Plan.

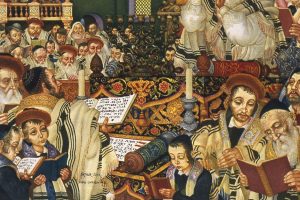

Which brings us to Philo. Not the flaky pastry dough but the very solid Jewish philosopher of the first century. Philo was an older contemporary of Jesus who lived in Alexandria, Egypt. Since Jesus hadn’t visited Egypt but for a brief flight in infancy, to our knowledge the two men never met. But we get the sense they would have liked each other. Both were serious about the responsibility of being fully alive, the power in words, and the necessity of clearly understanding the expectations of the God of Israel as revealed in the Jewish story.

Philo was a Man With a Plan. He intended to reconcile the mostly obscure beliefs of Judaism with the public richness of the Greco-Roman worldview. His take on biblical stories sounds incredibly modern, as he interpreted them allegorically rather than as literal history. Philo was an idea merchant, selling Hellenism to Jews and Judaism to the outside world. His other contemporary, Paul of Tarsus, doubtless would have argued Philo into the ground and maybe bloodied his nose. Yet Paul was himself an idea merchant, peddling a Christian take on the Jewish story to Greeks and Romans.

Most of us are familiar with at least one Philo quote, even if we didn’t know he said it: “Be kind, for everyone you meet is fighting a hard battle.” My favorite of his wares is this one: “The true name of eternity is today.” There are so many places this idea can take us! Today is happening right now, of course. But when we wake up tomorrow, it will still be today. And the next day as well. In fact yesterday was today as we lived it, which means all that you and I have ever known or can know is today.

Today is the vital hour, the only living hour, the hour upon which the future rises or falls. Because today is our everlasting living room, it can rightfully be identified as eternity. We reside in an endless realm of todays, stretching from the first moment of time into infinity. Which makes parallels between today and eternity completely fair and remarkably useful.

This is helpful to consider when the Letter to the Hebrews is on your plate, which is all this month in the readings at Mass. For anyone who is confused by the Letter to the Hebrews—let’s all stand up, and believe me, I’m on my feet here—the key to really hearing it is to appreciate that the writer is drawing an elaborate theological parallel between Jewish sacrifice and the Jesus sacrifice.

The actions of the Jewish priest are daily rituals, repeated to ensure harmony between heaven and earth once more. The actions of Jesus, by contrast, are once and for all—final and perfect, to use the word this letter prefers. The Jewish priestly ritual, enacted by a flawed mortal, is caught in the endless echo chamber of time. The priestly sacrifice of Jesus, performed by one made perfect in obedience, effectively breaks through the glass ceiling of the present to eternity.

Which do you prefer, reconciliation for now or for always? Think of it this way: If you could take out the trash once and for all rather than having to do it every single week, wouldn’t you opt for that? Most of us, out of laziness if nothing else, would choose the eternally effective option—or so we think. Yet our relationship to eternity is far less firm than our allegiance to today. We like the maneuverability of keeping our options open. We like to keep our hands on the steering wheel and to feel we’re in control of this beast of time we’re riding.

Take aging, for instance. We’re all doing it right now. Yet half of all Americans have no retirement plan, and 1 in 3 have zero dollars put away for their later years. It turns out even The Woman Without a Plan is better prepared for old age than 75 percent of my fellow citizens. Although it did take a lot of prodding from a fellow writer to get me to start that IRA 20 years ago. (Thank you, Bob!)

What could explain the phenomenon that most of us are standing like deer in headlights for an event that is surely arriving for nearly all of us? That is, unless we die young, which is not a retirement plan many would select. The plain truth is that you and I bank on today, not on tomorrow and much less on eternity. Our hearts and treasures are buried in today, and it’s very challenging to imagine ourselves residing in any other reality. Philo may view eternity as a horizon of endless todays, but we prefer to bury our faces in this today and give an ostrich-like rump to what comes next.

Recently I accompanied my 90-year-old mother to tour a campus of graduated care run by a group of Catholic sisters. My mother has lived in the same house for 70 years, including a decade without my dad. She’s perfectly capable of getting by on her own. For now. But at 90, she’ll be giving up her driver’s license soon, and that will be a game changer in her small town with limited services. The Catholic campus we visited is a half hour from where Mom has always lived. It has lovely cottages for independent living, shuttle services everywhere, plus dancing, card games, casino trips, movie nights, and daily Mass. It would provide the one thing she values most in her current home: a close parish feeling.

After viewing the premises, Mom admitted it was all very nice. It was good to have in her back pocket, an option for later if needed. In the 21st century, people her age can continue to talk about later as if it were a place they are heading to somewhere down the road, too far to presently contemplate. Mom could live another decade—or two. Why get an endgame together now, when today is so compelling and so comfortable?

You can see where The Woman Without a Plan gets her inspiration. And why it’s so hard for any of us to invest in eternity, with both feet planted firmly in today.

This article also appears in the November 2018 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 83, No. 11, pages 47–49).

Add comment