The problem is so tenacious because, despite its virtues and attributes, America is deeply racist and its democracy is flawed both economically and socially. All too many Americans believe justice will unfold painlessly or that its absence for black people will be tolerated tranquilly.

Justice for black people will not flow into society merely from court decisions nor from fountains of political oratory. Nor will a few token changes quell all the tempestuous yearnings of millions of disadvantaged black people. White America must recognize that justice for black people cannot be achieved without radical changes in the structure of our society. The comfortable, the entrenched, the privileged cannot continue to tremble at the prospect of change in the status quo.” (Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, A Testament of Hope, published posthumously in 1968)

It has been 50 years since the assassination of Rev. King. Since then, we Catholics, and Christians of all varieties, have often waited for the next prophetic leader to arise and bring about racial justice.

Meanwhile, those of us who are white often claim that racism no longer exists. As Bishop Dale Melczek points out in his excellent pastoral letter on racism, “Created in God’s Image” (2003), “There are those who lived in segregated neighborhoods and comment that there are no race problems in their world. Yet, when confronted with the logic that segregated neighborhoods are, of themselves, indicative of racism, the same people choose to remain locked in that denial or indifferent to pursuing any dialogue.”

Rather than opening our eyes to the de facto segregation in our neighborhoods and schools, many of us look the other way. Rather than rolling up our sleeves and doing the messy, local, difficult work of atoning for the original sins of this nation in slavery and genocide, nurturing our relationships with our Creator, and working to build a more just society, we tend to do nothing. We wait for God to act rather than looking for how to participate humbly in what God is already doing.

To remedy this problem, we need to reencounter Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. There are few figures whose ministry, words, and legacy can cut to the heart of the consciences of those Christians, Catholic and Protestant, who deny or remain passive in the face of racial injustice.

King remains a figure to whom multitudes of people still listen and who can galvanize the hearts, minds, and souls of the followers of Jesus Christ.

But there are few figures in U.S. history as seemingly well-known but as truly little-understood as Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. We need to encounter the real Rev. King, the de-sanitized prophet of racial and economic justice who will make us uncomfortable with his words and deeds of “tough love.”

If high school history books, news talking heads, and the occasional homily references are any indicator, the good Reverend only did a few things: He held lots of peaceful marches, he helped bring about the passage of civil rights and voting rights legislation, and he had a dream in 1963 about all human beings someday being judged not by the color of their skin but by the content of their character. He helps us feel good, and he was against violence. That’s about it.

But, as a famous professor of King’s theology told me in class many years ago, people do not get assassinated because they are nice and they make people feel good. Nor do they get killed because they are friends of the powerful and the status quo.

People get killed when they become too troublesome, too radical, too much of a threat to be allowed to live any longer. Lots of people, mostly white people, tried to kill King for the majority of his public life. But it is not a mere coincidence that he finally was done away with just at the time he was calling upon all poor people in the nation—black, white, Latino, Asian, Native American—to rise up, march on Washington as a nonviolent occupying army, and shut down the workings of the nation’s capital until the federal government took action to end poverty once and for all. This was the Poor People’s Campaign, initiated in 1967.

When a public figure starts calling not only for black freedom but for a multiracial, nonviolent, social revolution to eliminate the sibling scourges of racism, poverty, and militarism, that figure has signed his own death certificate. It is sad and cruel, but of little surprise, that on April 4, 1968, Rev. King was assassinated.

As our nation approaches the 50th anniversary of King’s assassination, rarely do we hear about the de-sanitized, inconvenient King.

Rarely do we hear about the King who publicly remarked that his dream from 1963 often had turned into a nightmare (“Address at the End of the Selma to Montgomery March”). Rarely do we hear about the King who was so troubled by the long history of white violence against blacks that he publicly wondered if black and white Christians actually worship the same God (“Letter from Birmingham City Jail”).

Rarely do we hear about the King who said he encountered an intensity of anti-black hatred and racism on the faces and in the actions of whites in Chicago—men, women, and children, mostly Catholic—that he had never encountered anywhere in the South and began to wonder if all whites were unconscious racists (1966 Chicago Campaign).

Rarely do we hear about the King who called for a nonviolent revolution to restructure the entire social and economic systems of the United States (1967 Poor People’s Campaign). Rarely do we hear about the King who charged white Americans with “cultural homicide” against African Americans, who declared “I’m Black and Beautiful,” and that the hour was late for redemption and so “America must be born again” before it’s too late (“Where Do We Go from Here?”). Or the King who preached, “But God has a way of even putting nations in their place. The God I worship has a way of saying, ‘Don’t play with me…Be still and know that I’m God. And if you don’t stop your reckless course, I’ll rise up and break the backbone of your power.’ And that can happen to America,” (“The Drum Major Instinct”). Rarely do we hear about that Rev. King.

After many years of studying, teaching, and writing about Rev. King, I have come to the conclusion that the majority of Americans, especially white Americans, have contented ourselves with the delusion of a “teddy bear” King. An amazing preacher and activist who just happened to be black and who advocated for peace, love, and harmony among the races.

This King was less a troublesome, troubled, doomed prophet of the biblical variety than a comforting, mellow peacekeeper of the “kumbaya” variety. He was a figure more concerned with assuaging the guilt of white people and rich people than achieving salvation from suffering for black people and poor people.

This is a problem for two reasons. First, it simplifies and sanitizes King. It deforms his person and legacy and reforms him in an image manufactured for economic gain or political posturing.

The result is the recent Super Bowl commercial in which King’s words are used to sell American trucks. Or Sean Hannity manipulating King’s words to serve a conservative political agenda. Or a U.S. Catholicism that oftentimes invokes King’s name in the pulpit but once a year to remind us of a dream and to absolve us of the responsibility to carry on the radical edge of his legacy.

Second, it lets us off the hook. We sanitize King’s prophetic edge and overlook his self-understanding as first and foremost a Christian minister. We make him super-human as opposed to an exceptionally gifted but flawed human being.

King was a womanizer who had many extra-marital affairs. There is a good reason why King preached, “I don’t know this morning about you, but I can make a testimony. You don’t need to go out this morning saying Martin Luther King is a saint. Oh, no. I want you to know this morning that I’m a sinner like all of God’s children. But I want to be a good man.” (“Unfulfilled Dreams”). As the F.B.I. built its file on King’s “anti-American” activities, it attempted to use recordings of his trysts as blackmail.

We also need to embrace this gifted, flawed, all-too-human King. Otherwise, he becomes an idol that absolves us of our current responsibility to struggle for racial justice.

We are in a time in which the insidious presence of white supremacy is no longer confined to the shadows of public life. King’s observation that opened this essay still holds true 50 years later: America remains saturated with racism and our democracy often is compromised by social and economic flaws.

Now, more than ever, we need the real King. We need the prophetic Christian minister who called for a nonviolent revolution and who gave his life so that we might achieve a greater degree of racial justice.

Yes, many aspects of life are much better in 2018 than in 1968. There are African Americans, and other people of color, represented in the most powerful aspects of American life. Nevertheless, African Americans and other people of color still bear the lion’s share of the burdens of U.S. society: grossly disproportionate rates of poverty and incarceration, lower life-expectancy, higher unemployment, voter disenfranchisement, harassment by law enforcement officials, and de facto segregation in housing and schools.

We are a far cry from King’s goal of the “beloved community” and only marginally closer to the beginnings of a truly integrated society. As King pointed out, “Integration is meaningless without the sharing of power. When I speak of integration, I don’t mean a romantic mixing of colors, I mean a real sharing of power and responsibility” (A Testament of Hope, HarperOne).

The hard truth is that racial injustice is alive and well. It has dire consequences for the minds, bodies, spirits, and communities of all of us, but in particular people of color. King’s observations from 1968 continue to resonate in 2018: “White America has allowed itself to be indifferent to racial prejudice and economic denial. It has treated them as superficial blemishes, but now awakes to the horrifying reality of a potentially fatal disease . . . The American people are infected with racism—that is the peril. Paradoxically, they also are infected with democratic ideals—that is the hope” (“Showdown for Nonviolence”).

There is work to do. And encountering the de-sanitized, prophetic voice of King is a good place to start. For no other figure in modern American history has the potential to cut to the consciences of Christians as deeply as Rev. King.

King reminds us to bring together both love and justice in learning to humbly participate in God’s work of dismantling racial inequality and creating a more racially just society. To this end, King’s words can guide us in our prayers, thoughts, and actions: “. . . we must keep God in the forefront. Let us be Christian in all of our actions. But I want to tell you tonight that it is not enough for us to talk about love. Love is one of the pivotal points of the Christian faith. There is another side called justice. And justice is really love in calculation. Justice is love correcting that which revolts against love” (“Address to the First Montgomery Improvement Association Mass Meeting”).

Let us allow the real King, the de-sanitized King, to trouble our consciences. And let us allow the real Rev. King to compel us to participate in God’s work of creating a more racially just world.

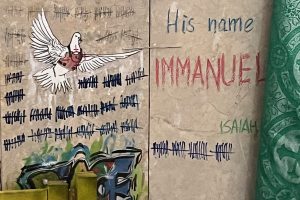

Image cc via LIFE

Add comment