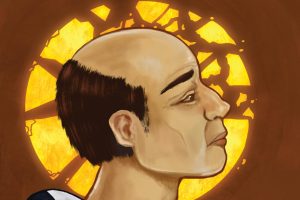

I first encountered her in a cold stone church in Périgueux, France. She stood in a corner, a young shepherdess with a plaster lamb looking up at her trustingly. Something about her—maybe the dark apricot color of her dress, or the surprising plainness of her face—captivated me. Whatever the reason, I snapped a picture and noted her name: St. Germaine Cousin.

Years later, in a book of saints, I stumbled upon her story. Just like the statue, Germaine’s tragic life speaks to me on an almost visceral level. It’s a story that leads me to ponder the hidden lives of the most vulnerable members of our society: the children.

St. Germaine was born in Pibrac, France in 1579. Her mother died when she was a baby, and her father remarried a woman named Hortense, the archetypal evil stepmother.

Hortense made no secret of her dislike for Germaine, who was born with a deformed right hand and had the disease of scrofula, which made sores erupt on her neck. This dislike took the form of neglect and abuse; Hortense deprived Germaine of food and made her sleep in the stable or in the space under the stairs. As a girl Germaine was sent to tend the sheep, another way to keep the ugly child out of her stepmother’s sight.

Germaine, though, turned this banishment into a closer relationship with the divine. Although she knew only the most basic elements of her faith, she developed a rich prayer life and personal friendship with God. She went to daily Mass and shared spiritual stories with the local children; she often gave her meager food scraps to beggars.

Her loving generosity—and her astonishing lack of resentment toward her stepmother—gradually earned her the villagers’ respect. As her reputation for holiness grew, her family had a change of heart and invited her back into the house, but Germaine preferred the humble bed she’d always known. One morning, when she was 22, her father went to wake her. He found her dead in her bed.

The story of Germaine is filled with pathos; it’s the Little Match Girl or Cinderella without the prince. On the face of it, it’s odd that this girl has such an impact on me. Germaine seems overly meek and humble, not the strong female figures I usually find compelling.

But this saint grabs me and won’t let me go. Perhaps it’s because I’ve always had a soft spot in my heart for the underdog. As a kid, I’d buy the shabby, shopworn stuffed animal rather than the brand new one. Now, as a high school teacher, my heart aches any time I see a teen sitting alone at lunch while his peers chat in comfortable groups. It’s hard not to feel pity for Germaine, ostracized merely because of a lack of beauty.

In recent years, this sympathy has grown deeper. As the mother of a toddler, I see more clearly than ever the vulnerability of the children whom God puts in our midst. They all need love and clean beds and security. It’s a deep satisfaction to provide that for my son, to be his safe harbor in a scary world, but the reality is that many children don’t have such a refuge.

Thousands of young people are abused; whether they are constantly told they are stupid or are beaten or even sold into slavery, such horrors happen in every neighborhood of the world. Such abuse has always pained me. Now, as a mom, it’s almost too much to bear.

Maybe that’s why Germaine’s story is ultimately so moving. Somehow she found a way to survive and to let her own spirit thrive in the midst of horrific treatment.

It would be a mistake to read her story as a pass to let abuse happen unchallenged; the sex-abuse scandals of our own church are proof of the evil of that kind of inaction. It’s equally wrong to conclude that children rescued from abuse don’t need extra support.

But what Germaine’s short life shows me is the astonishing resilience of children to whom the world is cruel. Courage is not just the province of soldiers and firefighters; it’s found in every victimized child who somehow manages to get through the day. Germaine’s story makes me realize that these kids have inner resources that I can’t imagine, that absolutely awe me. Her story pulls me more deeply into their needs, their struggles, their strength.

We owe them our love and our advocacy, these modern St. Germaines. At the very least, we can pray that they feel the divine love that this shepherdess knew, the presence of God that comforted her during unimaginable times.

She may have died quietly in her bed, but centuries later her resilience continues. It lives on in thousands of small wounded hearts, closer to us than we know.

This article originally appeared in the April 2009 issue of U.S. Catholic

Image: Wikimedia Commons cc via Didier Descouens.

Add comment