People of faith call the Bible the inspired word of God. It seems like such a simple matter: One presumes the Bible must be true, good, helpful, and instructive. That goodness includes its commandments and oracles, its heroes and prayers and stories. The moral lessons of these stories are supposed to be good for us. Right? So what do we do when a particular biblical story is a horror and its lesson sounds flat-out wrong?

Many folks who read the book of Judges—of all denominations—find the moral content of the book repellant. A few years back I was approached by an evangelical Protestant organization about supplying a commentary on Judges. I’m not an expert by any means, but they couldn’t locate a self-respecting Protestant commentator interested in dealing with the book. So I spent a summer boning up on Judges. And I began to appreciate why some folks would rather not.

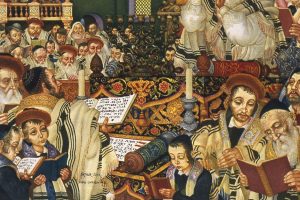

Take the disturbing story of Jephthah and his daughter in Chapter 11. It’s not the grisliest chapter of Judges, believe it or not, but it’s still deeply upsetting. Jephthah’s story is sad all the way through.

Jephthah begins life as the “illegitimate” son of Gilead, a married man who consorted with a prostitute. While his father rears him along with his “legitimate” sons, his half-brothers eventually grow up and drive Jephthah out of the home. Jephthah flees to another region and joins a gang of raiders, gaining a fierce reputation.

In time Israel finds itself at war with the Ammonites and every available fighting man is needed. The elders of his home region appeal to Jephthah to return and lead the fight. They offer him leadership over them if he wins the victory, a prestige Jephthah’s wounded self-esteem craves. On the way to battle, Jephthah makes a rash vow: If God helps him beat the Ammonites, Jephthah promises to sacrifice the first living creature that comes out of his house when he returns home. Many translations will simply render his vow as pertaining to “whoever” comes out of the house. It is more ambiguously a “whatever/whoever.”

It helps to know something about houses in Israel in 1200 B.C. The second floor was where the family lived. The first floor was where livestock and other supplies were kept safe for the night. It’s possible that Jephthah presumed an animal, fit for sacrifice, might emerge from the house first. The careless wording leaves room for the idea that a servant leading the animals out to pasture would be caught in the net of Jephthah’s vow. Fool that he was, it never occurred to the man that his only child might rush out to meet her father.

The moment Jephthah sees his dancing, tambourine-playing child, he blames her for ruining him. As soon as she understands the nature of her father’s vow, the daughter accepts her fate. She asks only for two months in the mountains to mourn her virginity with her friends. It’s stressed three times that Jephthah’s daughter remains a virgin. When she returns from the mountains, her father “did to her as he had vowed.”

Jephthah becomes one of 12 named judges in Israel, ruling for six years. That’s a short stint as judges go, since most ruled for 40 years, the biblical number for completion. This abbreviated leadership is the only biblical evidence that judgment was passed on Jephthah for his terrible vow. The book of Hebrews remembers Jephthah as a warrior loyal to God. It says nothing about his horrific failure as a father.

The story of Jephthah and his daughter has a lot of troublesome gaps, known elegantly as “narrative silences.” The most obvious one is: Where is God while all of this is going on? How does God view Jephthah’s careless vow, both in its pronouncement and its fulfillment? Why doesn’t God interrupt and save the child, as happens in another famous child sacrifice story involving Abraham and Isaac in Genesis 22? The silence from heaven seems to imply consent, or at least a divine disinterest in the outcome.

A second narrative gap involves Jephthah’s wife. Where is the girl’s mother while Jephthah is keeping his proud bargain with his God? Is Mrs. Jephthah dead or is she like Jephthah’s own mother—a casual acquaintance long gone? Is this a case of “like mother, like daughter,” as both females bow and submit to a rash man and his dangerous views on religion?

A third silence concerns the girl’s name. Why doesn’t she have one? Even God gets a proper name in the Bible. A name represents identity, volition, and personhood. When characters go unnamed, it’s because they aren’t regarded as actual players or are considered expendable (the way “Crewman Number Six” on Star Trek is marked for death in the opening scene). Jephthah’s unnamed daughter remains caught in her identity vis-à-vis her father. She is simply his property, to do with as he wishes.

The rabbis who comment on this story—and it’s important to note that they do, early and often, mostly with a stream of objections to the whole saga—point to another narrative silence: that of Phinehas, the priest at the local shrine. It’s inconceivable that, in the maidens’ two-month sojourn while mourning on the mountain, the local priest wouldn’t have been consulted on the questionable morality or viability of such a dark vow. It’s clear from a dozen passages in scripture that the God of Israel is irrevocably opposed to human sacrifice. Phinehas could have and should have revoked the vow. His non-appearance in the story creates another shudder for the Jewish reader.

One clue to the silences is repeated again and again in the book of Judges: This period of Israel’s history was a godless time, when “there was no king” and “everyone did what was right in their own sight.” When an entire community loses the moorings of genuine authority, the strong (and not the wise or good) take charge. Such leadership is rarely just, and the weak and innocent invariably suffer.

What makes the tale of Jephthah’s daughter most troubling for us is that she is hardly the last child sacrificed to the irresponsible ambition of a parent. Across the centuries we want to save her and continually we fail. One rabbi in the Middle Ages even suggests that Jephthah himself devised a way to rescue her by shutting her up on his property for the rest of her life. That way he did indeed keep his vow to sacrifice her (he never has heirs) and she remains a virgin (which is why she and her friends mourn only her virginity, and not her life, on the mountains). This reading unhappily resolves none of the injustices basic to the story.

What remains to this day is the annual mourning ritual that Jewish women continue to practice on behalf of Jephthah’s daughter. The ritual isn’t just about a nameless girl, of course. The women are mourning for themselves and for their daughters.

This article appeared in the October 2015 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 80, No. 10, page 47–49).

Image: Der siegreich Feldherr Jephta begegnet seiner Tochter, 1661, Hieronymus Francken III. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Add comment