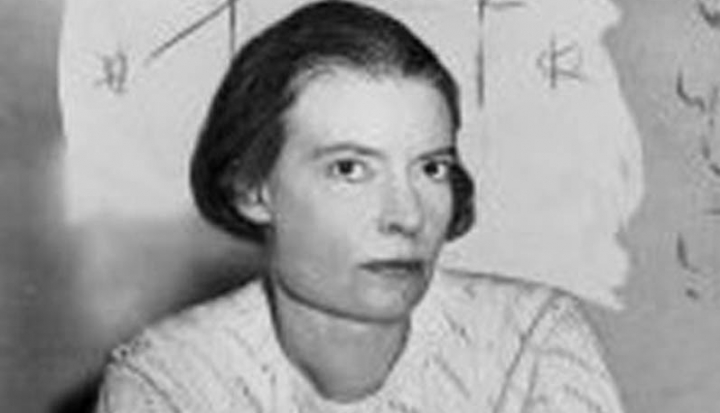

On Aug. 6, 1976 Dorothy Day was invited to address the World Eucharistic Congress in Philadelphia. The date of her talk was, of course, the Feast of the Transfiguration. But it was also, at least on the Catholic Worker calendar, the anniversary of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. Consequently we were astonished to learn that the Congress had scheduled for that day–of all days–a Mass to commemorate the armed forces.

Undoubtedly this called for a protest. Although I was not even a Catholic at that point, I thought nothing of going down to Philadelphia in the rickety CW truck to picket and pray with my friends in front of the bishops, generals, and military officers processing into the cathedral. Nothing pleased us more.

Yet all this weighed on Dorothy. Though she was always anxious about public speaking, this particular assignment carried a special burden. How would she find a way to balance a message of deep gratitude to the church along with her sadness?

Dorothy was 78 that summer; it was 43 years since–a recent convert, a laywoman, an unwed mother–she had started the Catholic Worker movement, thereby finding a way of integrating her Catholic faith and her passion for social justice. Some wondered how she managed to combine such traditional piety with her radical activism and pacifist witness. But for her there was no mystery; her witness was rooted in the deepest understanding of the Incarnation, the belief that God had entered into our history and our human experience, with all its joys and sufferings. God was truly present in the Eucharist–but also in the poor and in all the victims of violence.

For many years the bishops had held her at arm’s length, but now Dorothy had come to be regarded by many as the living conscience of the American Catholic Church. Hence the invitation. And yet this was the first time she had ever been invited to address such a gathering. As she noted, “If you live long enough, you are treated as a venerable survivor.”

She began her talk by describing her life among hungry people, in bread lines and in soup kitchens, before reflecting on the deep sacramentality of all creation. “My conversion began many years ago,” she said, “at a time when the material world around me began to speak in my heart of the love of God… Everything spoke to me of a Creator who satisfied all our hungers.” She spoke of her “love and gratitude to the church,” which had only grown through the years. “She was my mother and nourished me, and taught me.”

She went on to say that the church had also taught her the need for penance. And only then did she take up her harder message: “It is a fearful thought, that unless we do penance, we will perish. Our Creator gave us life, and the Eucharist to sustain our life. But we have given the world instruments of death of inconceivable magnitude. Today we are celebrating–how strange such a word–a Mass for the military, the ‘armed forces.’ No one in charge of the Eucharistic Congress had remembered what August 6 means in the minds of all who are dedicated to the work of peace.”

She concluded by alluding to our protest outside the cathedral and pleading to the bishops to regard the military Mass “and all our Masses today, as an act of penance, begging God to forgive us.”

The strain of this occasion was very great. Days later she suffered a heart attack and never spoke again in public.

This past November marked the 25th anniversary of Dorothy’s death in 1980. Slowly the church proceeds with the cause of her canonization. At the time of her death I would have been delighted to see her immediately proclaimed the patron saint of peace and justice. But with the passing years I have come to see that she was more than that. At a time when the church is so greatly divided between “liberal” and “conservative” factions, I see Dorothy as a saint of the “common ground,” someone who reconciled a great love for the church (which is, after all, all of us) with a capacity to recognize and suffer for its sins and failures.

At a time when the gospel seems more than ever out of step with the goals and values of our world, her message could not be more relevant. She presents us still with the challenge to begin this moment, where we are, to add to the balance of love in the world, to add to the balance of peace.

This article first appeared as a “Wise Guides” feature in the February 2006 issue of U.S. Catholic.

Robert Ellsberg is the former managing editor of The Catholic Worker and editor of Dorothy Day: Selected Writings (Orbis Books, 1992) and Blessed Among All Women: Women Saints, Prophets, and Witnesses of Our Time (Crossroad, 2005).

Add comment