Take a moment to write down 10 words that best describe you. If you’re stuck for ideas, you might start with the basic information on your driver’s license: name, gender, age. Some of us will quickly include nationality and religious affiliation, race or political leaning. Others will go straight for the adjectives central to our self-understanding (or perhaps self-idealization): honest, bold, kind, helpful, creative, funny. Few of us will choose to go all confessional and include the other side of our personal equation: pandering, fearful, self-congratulatory, judgmental.

Consider this list merely a stick figure of your ego (literally, your “I am”). For the record, on this particular morning, my “I am” goes something like this: female, Catholic, articulate, graying, book-lover, storyteller, sister, aunt, playful, serious. Some of these words describe what I am and others what I like to do. Still others situate me in relationships that are central to my life. I have a boatload of siblings and no children of my own, and my roles as sister and aunt have defined my sense of belonging in the world most profoundly.

If you’d asked for this list 20 years ago it surely would have been different. Ask me again next week and it might be shuffled a bit. But according to St. Paul, all of these details must be put aside. He views categories as potential obstacles in our common identity as church. After a spirited exhortation, pleading with the Colossians to “put to death” all earthly drives and attachments, Paul ends with an emphatic declaration: Here “there is no longer Greek and Jew, circumcised and uncircumcised, barbarian, Scythian, slave and free; but Christ is all and in all!”

Sometimes it’s clear why Paul made such a good missionary: He had to keep moving around when his zeal led him to make statements so deeply unpopular! Just imagine what it would take for you to crush your little list of 10 prime identifiers and toss them away for the sake of being church. In Paul’s society, it was no easier. Hellenized citizens were as proud of their superior Greek culture as the often separatist Jews were adamant about their moral superiority. Circumcision was not only a line drawn boldly in the sand, but an intimate scar dug into the flesh. Barbarians were defined as those who spoke no Greek: From the perspective of the Roman Empire, such a person was a lesser form of human. Scythians from north of the Black Sea were, to first-century historian Josephus at least, even lower: “slightly better than wild beasts.” A Roman slave was property and not a legal person. Roman society depended on the upholding of these distinct classes, and Jewish culture was by no means less interested in maintaining these boundaries.

One wonders, then, how Paul got up the gumption to brush these all-important categories away in his premiere model of church. If you are in Christ, you are Christ, Paul asserts. No part of the Body is less Christ than another, no matter what role he or she plays, finger or toe. And if Christ is all and in all, then whether you’ve been marked in your flesh with the sign of the covenant or are branded as your master’s household property is an irrelevant detail. One supposes that, to the son of Abraham and to the slave, such a detail was quite relevant. Paul’s breezy erasure would have been stunning to both.

Every Greek in Paul’s audience would have included that identity in the 10-item stick figure drawing of himself, as would every last Jew. Perhaps so-called barbarians and Scythians would have used other terms to describe themselves, but their sense of being outliers would also have included a belonging to some significant ethnicity. We don’t need to talk about how a Scythian feels about his Scythian-ness. I know how I feel about being female, and it surely makes a difference to most waking hours of my life that I am a woman and not a man on this planet.

Does Christ being all and in all make male- and female-ness moot in the church? Not as far as I can tell. My lack of a natural resemblance to Christ is regularly cited as a barrier to certain forms of leadership. While Paul doesn’t smudge the gender lines in this passage of Colossians, he does extend the argument elsewhere in Galatians 3:28: “. . . there is not male and female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus.” I appreciate Paul’s position: He wants the fractious Galatians to stop pulling the community apart and to start pulling together as the unified and harmonious Body of Christ. Point taken. To which a Galatian woman might reply: I’ll take female off my ego list as soon as the fellas take male off theirs.

Truth to tell, some men might not have man on their “I am” list to begin with—any more than I, a person of European descent some generations back, put white on mine. The dominant culture rarely thinks of their dominance in terms of tribal identity. It defines their worldview so seamlessly that it may be invisible to them. Just as women may be more conscious of their otherness (even when they obtain a slight majority in the population), so a black, Spanish-speaking lesbian will be more inclined to note such distinctions in her ego stick figure list of descriptors. In placid childhood I never thought of myself as a child. In turbulent adolescence I was acutely conscious of being a teenager.

What is Paul saying to the Colossians when he insists that Christ is an identity which supersedes all others? Probably more and less than most of us would like to hear. Take slavery, for example. It has troubled Christians for centuries that, as much as Paul vouches for runaway slave Onesimus in his letter to his master Philemon, Paul never tells Philemon outright that slavery is a rotten institution that cries to heaven for justice and that Philemon must liberate his brother in Christ. So: In Christ it doesn’t matter whether you’re a slave or free—but that doesn’t mean a man who is baptized with his entire household is obliged to free his slaves. Or treat his wife and children with the same respect due to him. Or invite a barbarian home to supper! It’s obvious from Paul’s letters that the apostle could barely get baptized Jews and Greeks to sit down together at the table of the Lord. No one ever said church was going to be a cakewalk.

That little flag of “I am” keeps waving over my life and yours, proclaiming our selves, our walled-off clans, and the allegiances to which we pledge our true loyalties. We might confess we’re used to having a Greek to look down on, a barbarian to whom we don’t speak, a Scythian to fear, or a slave or two in our possession. If being in Christ means giving up these essential luxuries of the ego and more, then maybe the price of admission is too steep. If Christ being all and in all is the cosmic target, then we the church clearly have more dreaming to do.

This article also appears in the July 2016 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 81, No. 7, pages 47–49).

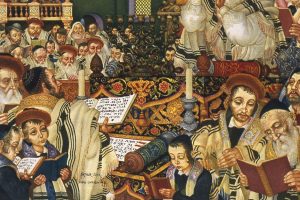

Image: Christus Pantocrator in the apsis of the cathedral of Cefalù, Via Wikimedia Commons.

Add comment