Betrayal by a friend. It is one of the bitterest cups we ever drink.

In the Gospel of John, Jesus speaks movingly at the Last Supper of a new kind of friendship: a friendship based not on reciprocal gain, but on mutual service; he kneels before the disciples and washes their feet, wiping them dry with a towel tied around himself (John 13:3–5). This is a friendship based not on patronage by a superior to an inferior, but in compassion. Today, Christ continues to calls each of us to equal dignity and love. “I do not call you servants,” says Jesus to his disciples, “but I have called your friends” (John 15:15). This is a love based on affinity, kindness, and loyalty. A love that ever seeks the good of the other.

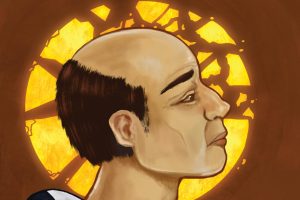

Even in our closest relationships, it is difficult to live up to Christ’s model of a friendship based in compassion and mutual love. “Et tu, Brute?” asked the dying Caesar, betrayed by one he thought was his close friend. Who of us has not at least once asked that of someone we love? And who of us has not at least once given the kiss of betrayal?

I once conducted a brief spiritual reflection for hospice workers that explored the nature of vocation and how to hear what God is calling us to be. As part of the reflection, each person in the room was to choose a shell from a pretty basket of varied seashells. This would be a shell of their own, one to keep on their desk or in their car, one to lift to their ear in moments of stress, confusion, or weariness. In that strange, underwater sound, a song from the place where the shell’s curves meet the intricate architecture of our ears, I challenged the participants to hear again their call to serve the sick and the dying. This call is unmoved by the vagaries of day-to-day work and remains as constant and reliable as the tidal back and forth of the sea.

A friend of mine was at that meeting. I did not speak to him; we were at odds and sitting far from each other. We both needed to forgive the other. We both, I think, heard some nasty static distorting the hushing calm of the seashells. It was a long meeting.

That evening, however, he sent me an email thanking me for the reflection, and he told me about his choice of shell. He wrote, “I took with me a scallop shell, the symbol of the pilgrim, of the Way of Santiago de Compostela. . . . It is now on my desk.” His was a peacemaking gesture, reminding me that we were both walking the same way, on the same path, and that often (though not always) we walked together.

We have subsequently had further disagreements; at times both of us have felt betrayed by the other. To the extent that my friend’s shell was a symbol of peacemaking as well as of pilgrimage, it has been broken and re-broken. When arguing with each other, we walk our separate ways as we would walk on beaches littered with sharp-edged, broken shells: Our feet are bloodied. This is not how Christ models friendship. This is the way of Judas. The way of one who prefers an easy 30 silver coins to the hard, redeeming work of fellowship. In its own way, it is a killing of self even as Judas did.

Jesus reminds us to love our neighbor as ourselves. When we turn against a friend, when we turn away from philia (“brotherly love”), we commit a kind of suicide. When we mortals commit a portion of our finite time on this earth to the good of another—whatever the cost—we become something holy. And yet, so often, we turn away from this sacred vocation.

That said, there are friendships that must be abandoned along the way. Some that once were healing and life-nurturing can become corroded, can dwindle to less than a breath with distance, can subside gently into darkness like the tide washing out to sea. There are friendships that break not just our hearts but also our souls, friendships that are destructive, co-dependent, or manipulative. Friendships that are not really friendships.

As disciples, we need to be open to the nuances of the story of Jesus’ death. The scourging, the nails, the crown of thorns all get a lot of dramatic play. But perhaps the greatest suffering he endured was his abandonment by his friends. Judas gave the kiss of death, Peter pretended not to know him, others ran away and hid, one preferring to be stripped of his clothes rather than stand beside the one he called teacher. At the last, Jesus felt that even his Father had forsaken him: “My God, my God, why have you abandoned me?” (Matthew 27:45–46).

In the wee hours of this morning, I held a woman in my arms at the hospital whose husband had had a severe heart attack. Her hands shook, her voice trembled. She was desperate that he not die. She pleaded with God, almost literally on her knees, to save him. More than that, however, she also prayed, “Help me to know you are here, dear God. Please be real. Please help me to believe.” She wept and took my hand in a crushing hold. I felt the heavy burden of her love, of her need for a friend. I will be honest: I, too, felt the fear of God’s betrayal. I told her God was present, always present—but is that true? I feared I, too, would betray this woman. I feared friendship would fail (mine with her? mine with God?) and that could scar her forever. Together we sat in the hospital atrium, troubled and fear-filled pilgrims, waiting for the dawn together.

It came. And with it, just as in the Bible story, came newly resurrected life. Her husband survived surgery, and the doctor reported that his prognosis was good. “I will pray for you and your family always,” the woman said to me in her gratitude. “I will never, ever forget you.” She promised love and loyalty. She promised, in fact, to be my friend.

I have a small, intricate conch shell that I chose for myself on the same day I led the reflection for our hospice meeting. Today, after sitting with this woman as she waited, I hear in its deep-sea whisper a call not just to be friends to the lonely and afflicted, but also to forgive those whom I once called friend, those who in fact helped to set me on this way. Vocation is not just how you use with your mind and hands or how you fill your hours and days. It is about the disposition of your heart: a willingness, ultimately, to forgive the Judases in your life and to forgive your own betrayals of those you love. “Peter, do you love me?” Jesus asks his so-fallible best friend in John 21 (15). It took Peter the rest of his life to answer that question.

As it will take us the rest of ours. Let it be. Shalom.

Add comment