For nearly 2,000 years, the chair of Peter has been occupied by a motley crew of saints and sinners. In the course of teaching church history in a seminary, I have more than once witnessed a collective blush as we cover the foibles of the 18-year-old Pope John XII or the infamous Rodrigo Borgia, Pope Alexander VI. Once we hit the early modern period, we encounter popes who stumbled when it came to fully engaging with modernity. Popes Pius IX, with his Syllabus of Errors, and Pius X, with the Oath Against Modernism, are but two examples. Even Pius XII presents a challenge, given the increased conservatism of his final years.

It always feels like a breath of fresh air to me when we reach the year 1958 and the election of Angelo Roncalli as Pope John XXIII. Here was a pope who was courageous and forward-thinking, and who even possessed a sense of humor. When asked how many people worked at the Vatican, he famously quipped, “About half of them.”

This past year, as we closed in on 1958, my students and I got an unexpected “living history” lesson while watching the coverage of the papal conclave. When it was announced that the elected Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio of Argentina would take the name Pope Francis, many hopes were raised.

The excitement only grew in the days that followed, as we learned more about our newly elected pope. And it became clear from the start that Francis would lead the church in new directions, challenging the people of God to rediscover the Jesus of the gospels—the Jesus who announced the kingdom of God to all, especially to the poor and the marginalized. This was a man who would lead by example, who had spent his life out among the people, a shepherd who “smelled of the sheep.”

As our class returned to the study of Pope John XXIII, the similarities between the two men became even more apparent. Angelo Roncalli had also spent most of his clerical life among the people. The son of tenant farmers, he was able to study for the priesthood only through the generosity of others. He had seen the horrors of war, and, as a medic and chaplain during World War I and later in diplomatic posts to Bulgaria, Turkey, Greece, and France, he witnessed firsthand the deep divisions between peoples.

Throughout this time, Roncalli had been a builder of bridges, reaching out to members of the Orthodox Church and working to alleviate the suffering of people of all faiths during the Second World War.

Even in what was considered to be his final assignment as Patriarch of Venice, Roncalli’s outgoing personality kept him frequenting the book stalls and theaters and taking public transportation. So it was no surprise that as pope he continued to reach out to others and to be a bridge builder between Catholics and people who had seldom heard a kind word from the Catholic Church.

If Pope John’s vision wasn’t apparent to others at the moment of his election, it became crystal clear 90 days into his pontificate when he announced the Second Vatican Council. Pope John stated that this would be an ecumenical council, not simply in the traditional sense of the word, but that he was including a “renewed cordial invitation to the faithful of the separated communities to participate with us in this quest for unity and grace.” When the Protestant and Orthodox observers arrived at the council three years later, they were amazed to discover they had been given the best seats in the house. They were welcome indeed.

John XXIII built other bridges as well, many long overdue. On the pope’s 80th birthday, Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev sent him birthday greetings. While his advisers recommended against responding, John replied with thanks and a promise to pray for the people of Russia. This was the first formal communication between the Vatican and the Kremlin since 1917, and it led to a thaw in relations that allowed John, during the Cuban Missile Crisis, to issue a public plea for peace that permitted Khrushchev to back down without losing face.

John went on to write Pacem in Terris (On Peace), his last encyclical issued in April 1963, in which he called on people of goodwill to work together for peace, even if it meant cooperation with those whose political systems were based upon error. It was simply part of John’s nature to look beyond erroneous ideology to see the good-hearted people who had embraced it. He once referred to a socialist friend as “my favorite infidel.”

During the council itself, Pope John’s ardent desire was that the bishops would be able to address head-on the challenges faced by the modern world. Ecumenism, relations with the Jews, and issues of justice were deeply important to Pope John, and he felt it was important for the bishops to be able to discuss them openly, without the members of the Curia placing obstacles in the way. When the Curia objected to the heated debates, Pope John calmed their fears by reminding them that bishops had behaved far worse at earlier councils.

While he didn’t live to see Vatican II concluded, Pope John opened the dialogue that led to a renewed church that could minister effectively in the 21st century.

On April 27, Pope Francis formally canonized Pope John XXIII. There is something deeply fitting about this. For me as a priest-professor, and for my seminarians, it is a sign of hope. We are living in a church that still struggles with what it means to engage fully with the world.

Shining the light of the gospel onto extremely complicated situations is no easy task. Pope John XXIII provided us with an excellent example of how to do so with peace and with joy. And as he joins the official list of saints, he reminds us that, as a church, our journey toward God is fundamentally a journey we make with all of our brothers and sisters throughout the world, regardless of their religious or political beliefs.

May we continue that journey with the same spirit of openness that guided John XXIII.

This article appeared in the May 2014 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 79, No. 5, pages 47-48).

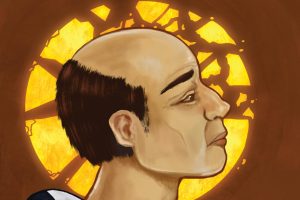

Image: John Nava/www.johnnava.com

Add comment