The value of a faith community can’t be crunched on a balance sheet.

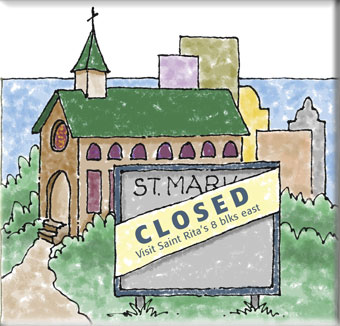

Thirteen in Miami, 52 in Cleveland, 33 in Albany, New York. No, these aren’t Chrysler dealerships or Starbucks franchises closing due to the recession but parishes that will be shuttered this year in three dioceses. The diocesan announcements do, however, share something in common with their corporate counterparts: The news comes with the just about the same amount of pastoral care and sensitivity-little if any.

From Boston, which closed or merged 65 parishes in 2004, to the most recent news from Miami, parishioners invariably express surprise, shock, and bewilderment. Even in those places such as Albany, where a consultative process took place, parishioners often feel suspicious and deeply wronged by the outcomes. “[The process] did nothing but pit priest against priest, parish against parish, and parishioners against parishioners,” said one Albany Catholic, according to the city’s Times-Union newspaper.

Parish consolidations are nothing new, but one has to wonder why we’ve never been able to get the formula down. Diocese after diocese repeats the same mistakes-lack of transparency in both process and final decisions.

But even more, no one seems to question anymore the necessity of closing churches in the first place. From chancery to rectory to parish home, the common “wisdom” is that dioceses have no choice but to shutter small, struggling parishes, especially in city neighborhoods and rural areas whose once-large Catholic populations moved to the suburbs a generation ago. Parishioners who protest are usually dismissed as unable to deal with reality.

But there has to be a better way to deal with small churches than aping the American capitalist model, treating them like diocesan franchises and shutting down underperforming outlets.

Dioceses always highlight the financial issues, especially when a parish that seems to have enough members gets closed anyway. Most Protestant congregation in the United States have fewer than 100 Sunday worshipers, and they keep going, admittedly not without difficulty. Why can’t we?

What’s killing many parishes is the sheer cost of maintaining properties. While beautiful, many of our older urban churches are just too big for the numbers they now house. But that’s no reason to close a parish just because we need to downsize a church. It would be far better to sell or lease the block-size parish plants. Who says a Catholic assembly can’t celebrate Eucharist in a storefront or strip mall?

There can be no doubt that the shortage of priests is also a core issue. But a single, bigger parish isn’t necessarily better for priests-who among them signed up to run a megachurch?-and it also risks making Catholic churches into faceless hordes rather than living communities of Christians who actually know each other. It would be a great loss to the church indeed if the suburban superparish became the only viable model and location for a Catholic community.

With the Vatican unwilling to tackle the issues surrounding the priest shortage, dioceses have to make do with the men they have. While a resident pastor is nice, many parishes can thrive with a lay administrator and a part-time priest. Fourteen of the 90 parishes of Diocese of San Bernardino, California have an administrator in case the bishop is unable to supply a priest. Why not give that arrangement a try more broadly? Lay leadership may well result in a more engaged laity in the parish to boot.

In the end, however, what needs to be shut down is not every endangered parish but the branch-office mentality that has gripped too many dioceses. Even if some parishes must close, that decision shouldn’t be made through master plans and consultations, which inevitably pit parishes and people against each other. Every parish deserves its own process, and chanceries would better serve struggling communities by working with them to chart a new course.

One size will not fit all, but we may surprise ourselves with our creativity, even our ability to accept loss. It is certainly true that the urban, immigrant parish model of the 1950s is dead and gone, but that doesn’t have to mean a funeral for the living parishes that are left.

This article appeard in the August 2009 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 74, No. 8, page. 8).

Image: Tom Wright

Add comment