One may not expect to find a Christian monastery in the mountains of Syria, much less one led by an Italian Jesuit. But Deir Mar Musa al-Habashi (The Monastery of St. Moses the Abyssinian) awaits the pilgrim willing to climb the hundreds of steps to reach it. Though monks first lived here in the sixth century, it has found new life since 1991 as a place of dialogue for Christians and Muslims.

Father Paolo Dall’Oglio, who first visited the ruins of Mar Musa during a retreat in 1982 and now leads the community of men and women, emphasizes Abraham as the patron of the monastery’s work. “Abraham is the example of hospitality because he received the three angels,” says Dall’Oglio. “He prayed that his son Ishmael be blessed by God and was also the father of Isaac. He’s really a man with a big heart to be the father of all of us.”

Dall’Oglio acknowledges that some may fear the encounter between Christianity and Islam. But he says the long history of coexistence in Syria and the rest of Middle East—the “human biodiversity” of the area—should give us hope for a common path forward.

“It’s OK if we don’t know what the future holds but still feel hopeful,” he says. “The world has changed many times. We should try to breathe properly with that perspective. That will overcome our fear.”

What is the connection between Christian monasticism and interreligious dialogue?

It’s important first to know a little history. Christian monastic life started in Egypt and migrated quickly into the Jordan River valley and then north to this place. By the sixth century, hermits started to live here, probably a group of monks whose Christology was considered heretical. They came here to be close to the pilgrimage routes but away from the Holy Land, where those in power demanded theological orthodoxy.

These monks lived in caves and prayed together once a week. Not long after some started taking care of guests as well as the sick, old, and mentally ill, so there was a need for common services. That’s how the community life began.

In the seventh century Muslims arrived from the east. At the time of the invasion, this area was ruled by an Arabic Christian kingdom. When the Muslims came, many Arabic speakers remained Christian and still are today.

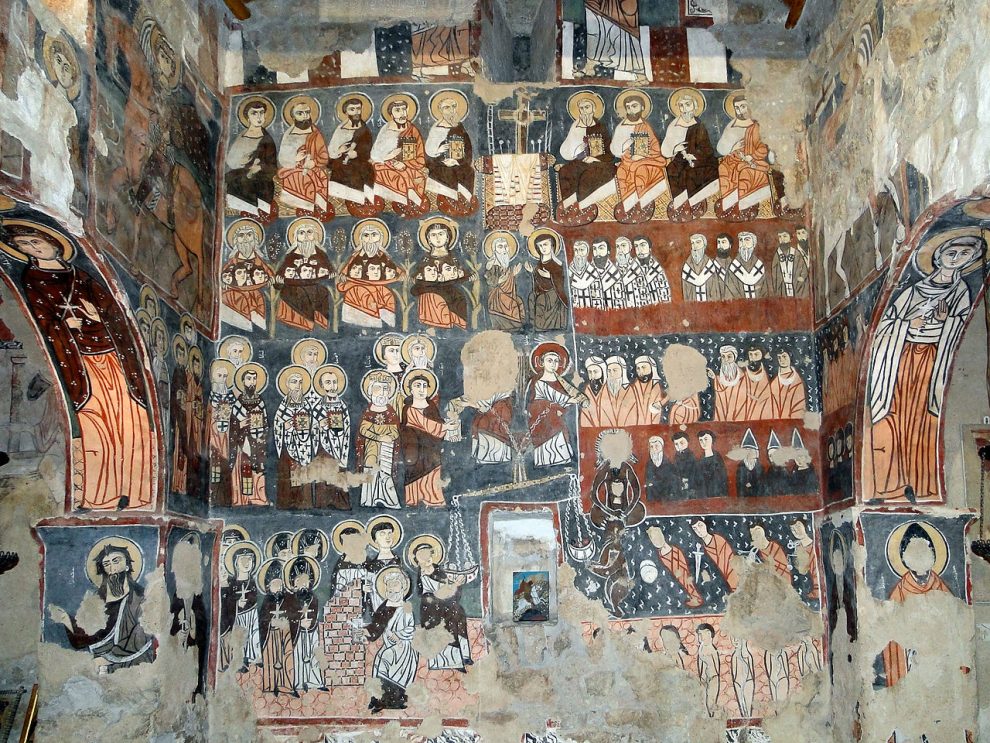

Christians were able to build churches and worship freely even after the Islamic invasion. As late as the 11th century, long after the Muslim conquest, they built the monastery church and decorated it in a magnificent way. There is still an Arabic inscription on the wall giving the Islamic date for the church’s construction and the words, “In the name of God, the Merciful, the Compassionate.”

It’s also important to know that a monastery is a place that is considered holy not only by Christians but also by Muslims. From the time of the Prophet Muhammad—may the peace and blessing of God be upon him—monasteries have been visited, respected, protected, and loved by Muslims; monasticism is really part of the Arab Islamic culture. When we speak about that civilization, we have to keep in mind that it was an Islamic, Christian, and Jewish civilization. Christians and Jews fully participated in creating that civilization.

So there was a climate of cooperation?

In Medina in what is today Saudi Arabia, when Muhammad came to power, agreements were signed to respect and tolerate Christians and Jews within the Islamic state. It’s a constitutional, structural issue.

From the theological point of view, there is an enormous consideration for the Torah and for the gospel in the Quran. There is a deep conviction in the Muslim community that Jews and Christians have been created and called by God; in the Muslim view those communities come from heaven.

Though the Islamic vision of the future sees Islam as the last word of history, Christians and Jews will still be companions in the movement to the end. That’s why the monastery is a holy, shared place.

How does this monastery fit in to that shared vision today?

Even though this monastery was abandoned in the 18th century, local Christians tried to keep it from becoming a ruin. Still, by the 1970s all the roofs had been destroyed. In 1975 I was sent by Father Pedro Arrupe, the Jesuit general, to commit myself to the service of dialogue between Christians and Muslims. That was the beginning of the second story of this place and how it became a place of meeting and of relationship.

I came here to pray for 10 days in 1982 and discovered three priorities for my life. I felt that the first priority was spiritual life. If we don’t break out of the natural ethnic and tribal belonging, we can’t open ourselves to breathe the wind of the Spirit. We will fight all the time just because we don’t understand each other.

But with the Holy Spirit of God, the one who created heaven and earth, we breathe properly, and things can move and change. Contemplative life is something shared by our traditions, including Eastern and Western Christianity and the Sufi Islamic mystical tradition, so it can be a starting place for our relationship.

The second priority is simplicity of life, an evangelical asceticism, which means manual work. If I speak with Muslims, I would call it the “lifestyle of the prophets.” In the Quranic tradition, most of the prophets were shepherds: David and Moses, for example. Jesus was the good shepherd, and Muhammad was a shepherd in his younger days.

The third priority is hospitality. Hospitality is a political program, the exact opposite of interethnic, intertribal, international fights. Hospitality is the real root of civilization because it goes outside the family to create relationships with and welcome the stranger. Through hospitality many things change.

The father of hospitality is Abraham, and Abraham is the guest of God in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, so he’s a big symbol for all three. That’s why Deir Mar Musa is part of the Abraham Path Project, which seeks to create a pilgrimage route following the ancient patriarch’s footsteps from Turkey to Hebron in the West Bank.

In the United States we speak a lot about “tolerance.” Is that the same as hospitality?

I don’t know much about the United States, but what I understand is that everybody came to this new holy land, each one keeping his view and his dream—the Jewish dream, the Christian dream, and so on—agreeing to have a common society in which everybody can be themselves without walking on others’ spaces. I have my religion, you have yours. We respect each other, and that means we have agreed to create a pluralistic society.

This is a good starting point because it eliminates religious violence, but it is not enough in the long term to create peace in the world. We need a shared vision, and a shared vision requires empathy. We need to share destinies, hopes, and even religious expectations.

This is much more than respect or tolerance. For us Christians it would be love, but I think in the Islamic Arab world, the word would be hospitality, the actions through which the stranger comes to be part of my home, part of my community, part of my vision for present and future harmony.

This means theological evolution. We will have to change our theological understanding because of the presence of the other in our lives.

Some people are afraid of that kind of hospitality. What might it lead to?

I’d like to know what will happen in 500 years, but I’m a citizen of my time. Today, there are two different major movements in the world from the cultural point of view. One is what we can easily call syncretic, a coming together of elements. Everything is mixed up like a salad: a little bit from Christianity, a little bit from Islam, a little bit from Judaism, a little from Buddhism, and so on.

Youth today are all more or less syncretic, from their clothes to their symbols to what they see as beautiful. Although our religious leaders denounce syncretism, we have to accept the reality of syncretism because it is a cultural fact.

But here, on the other hand, we are trying the second path: faithfulness. We seek to be faithful in order to keep for the next generation the spiritual, cultural, and theological diversity of our traditions. Faithfulness argues that when you mix everything, you lose a lot of what is unique to each tradition: the harmony, the beauty, the coherence. The capacity to initiate youth to a real spiritual life comes from the depth of our traditions.

Each tradition is a gift for humanity, whether Jewish, Christian, Muslim, Hindu, or Buddhist. To keep this gift, you have to know your history, feel your roots, carry your responsibility.

Is there a connection between faithfulness and interreligious dialogue?

When you are faithful, dialogue is an epiphany. In dialogue you meet someone from another world. Something really new happens and both parties are deeply changed by the meeting.

When the meeting takes place in hospitality, when God is the real guest, then it’s an occasion for God to show up. It’s an epiphany. We feel a particular joy and hope and light. Something new is happening, and this is hope for humanity. Real peace can happen, real brotherhood can happen.

Seeking the logic and desire of God in this religious melting pot is important. Do you think that God spoke with people only until 1,500 years ago and now refuses to speak? God isn’t saying, “I’ll not speak with you anymore. Go to the books, I’m tired.” God is speaking today, thanks be to him.

Can you think of a time where you had the feeling of God showing up?

There are so many. In this room there are Iraqis and Americans visiting who are looking to create the kind of hope that is the opposite of the “clash of civilizations.” In that, God is really present. At this table today, these two cultural continents are meeting, and I’m feeling moved by hope.

I also think of a Sudanese friend, a Sufi master. He has been very important for me, and I’ve learned much from him. We have had, at different times, moments in which our meeting changed both of us, showing us that our religions are not created to be foreign to each other but are really meant to bring about divine harmony, which is our responsibility to humbly create.

What do you think prevents the West and the Muslim world from meeting in this way?

First of all, we here in the Middle East are jealous of the United States, jealous of democracy, of the capacity to choose. Americans got tired of Bush, and now they have Obama. It’s incredible, being able to change the world by putting one name instead of another on a ballot. We are jealous of that.

We are also afraid of the power of the United States. It keeps democracy for itself and is not able to share real democracy with others. We are afraid that its people are strong and rich for themselves and don’t have any attitude of real solidarity.

From our perspective, it’s like Americans look in a mirror and see only from the neck up: shaved with teeth brushed and everything is all right. But what’s not in the mirror, from the neck down, is dirty and aggressive and violent.

What’s in the mirror is America’s idealization of itself, but it is not what the United States exports to others.

Then there is the issue of the Holy Land. The Bible and Quran and gospel are all holy. This is the land of the holiness of those books. You have to understand that for Muslims—from Mosul to Cairo to Morocco to Sudan to Nigeria to Indonesia to the United States—Jerusalem is holy. It is as holy as Mecca.

I hope there can be something of an internationalization of the holy town of Jerusalem, a U.N. mandate or something, that respects the rights of Muslim and Christian Arabs and makes Palestine bearable to live in. Billions of dollars are offered to the Jewish state; something in exchange has to be given for world peace.

In the sharing of the holiness of that place, there is a prophecy of a shared world.

As a Christian, what have you come to appreciate about Islam?

The mystical dimension is the most important for me. There is a religious feeling of the present holiness of God, active and really there, absolute and merciful and loving in this very moment. Everything is unified by holiness: the person, the family, the society, the world. Muslims have a feeling for the holiness of life, of God’s real and personal presence within it. God is really taking care of you as a father.

At the very center of this issue comes a deep desire for harmony, harmony in the family and in society. Nature created by God is multidimensional and complex. Muslim life is a contemplation on the harmony of the world created by God. The Islamic town is very free, seemingly disorganized, but there is a deep harmony that is able to pull together the movement, which reflects the complexity of what God has created.

Then there is the idea that consumerism is not the best model for humanity, and in this way Islam resists the globalization coming from the West. Although many Muslims are completely drunk on consumerism, consumerism is not the Muslim model. For Muslims it is an issue of human dignity; they are completely revolted by some images and movies from the West, which they see as lacking respect for the dignity of human beings.

How should Catholics think about the Prophet Muhammad?

It would be good to read a book about the life of Muhammad and his community, but this would not be enough. When you see a Muslim praying and being hospitable, merciful, and faithful, a person of piety and humility, and you see his enormous love for the Prophet, that’s something else.

There is an enormous desire among Muslims to repeat the attitude and virtues of the Prophet, to organize life in obedience to the Prophet. What happened in the soul of Muhammad is still relevant for more than a billion people. Through the souls of devoted, humble, real Muslims, you will discover something of the soul of the Prophet.

It is like the piety of Catholics for the Virgin Mary. We have none of her letters, we don’t have her speeches, we don’t have sermons, just some words written by Luke. All we have is her “yes.” It is the yes inside a single human being’s soul, and this has changed the destiny of heaven and earth.

For Muslims, Muhammad’s soul is the place of the revelation through which God’s word reforms the world.

This is what happens to any Muslim praying. He puts himself before God in the space of the revelation of the Quran, in the holy space of the soul of the Prophet. We Christians should be interested in discovering the relevance and depth and beauty Muslims find there.

The Christians of the Middle East are leaving. What happens if those churches cease to exist?

Christians have been here for 2,000 years and have a rich heritage of theology and tradition. Now they are leaving, and that’s a disaster for human cultural biodiversity here.

The reasons people are leaving vary: economic issues, lack of democracy, lack of health care. When you find a way to have a better life, you go, especially when you feel endangered.

Muslims, too, value the fact that this community is deeply plural. They feel the departure of Christians is a loss, and some important Muslims are saying they want to keep “our” Christians. When they go deeper, they even say they want to bring back the Jews who long lived here. These people are part of this civilization and culture, and it’s terrible to have lost them.

We all long for peace in Jerusalem and Israel and Palestine, because it will be a way to bring everyone back, to restore the historical civilization of cultural and spiritual diversity. This is my feeling as well.

What’s at stake for the future of humanity if we don’t find a way to get this right?

I will speak in terms of science fiction. I’m afraid that when human beings start to go out into space, we will still be fighting about religion and will carry a conflict mentality out into the universe.

I hope that we will together face the fact that the planet is not big enough for all of us, and we have the capacity to create a vision for the infinite destiny of human beings. We need to build real, deep harmony. We have to create this now; we have to make a spiritual vessel that can carry us forward together.

Image: Wikimedia Commons

Add comment