One day I was home, a familiar comfortable place; the next day I was a stranger in a strange land. It was Nov. 3, 1960, the date of my exile from my home in Cuba. It was also the feast day of St. Martín de Porres, a Dominican friar from Peru. St. Martín, I now believe, was assigned to be my guide in this strange land, the United States.

Although not many English-speaking Catholics are familiar with St. Martín, he is one of the most popular saints in Latin America. St. Martín was the son of the white, blue-eyed hidalgo (a Spanish noble) Don Juan de Porres and the freed black slave Ana Velázquez. Born in Lima on Dec. 9, 1575, Martín also was born into a kind of exile. His own father would not acknowledge him as his son in public. The baptismal entry in the registry of the church of San Sebastian in Lima reads simply: “On Wednesday the ninth of November of 1579, I baptized Martín, son of an unknown father.”

At the age of 16, Martín presented himself as donado to the Dominican friars of the Monastery of the Holy Rosary. Donados were members of the Third Order who received food and lodging for the work they did as lay helpers. In Spanish eyes this work was menial and not fit even for the lay brothers of the monastery.

St. Martín, however, saw things differently. At the door of the monastery, he began to greet the conquered Inca, the African slave, the homeless Spanish poor, and even dogs and cats who had been brutally abused. Standing at the door, a border between the friar’s holy life and the city’s crushing cruelty, made St. Martín a guide for the people of Lima in his day and also for us today. Out of that menial position, St. Martín became known for his skill in healing; his social work among widows, orphans, and prostitutes; his founding of hospitals and orphanages; his work with the indigenous, black, and mixed-race poor of the city; and for his love of animals. Indeed San Martín was known as the “St. Francis of the Americas.”

St. Martín transformed living at the margins of society into service at the door of the kingdom of God. He saw attending the monastery’s entrance as attending the very entrance of God’s kingdom. For this reason, St. Martín has been my guide and light. Rather than curse the marginal life that was my exile, I began to see it as a door into God’s home. I believe it is also the reason so many in Latin America see Martín as a guide as well. Those who find themselves outside of society find themselves welcomed home at the door attended by St. Martín.

There is more to St. Martín than an affable social worker. The stories of his compassion for the abandoned and maltreated animals of his city best reveal the heart of St. Martín’s sanctity.

In one of the most famous stories, a Dominican friar walked into a room near the kitchen to find a strange sight: At the feet of St. Martín were a dog and a cat eating peacefully from the same bowl of soup. The friar was about to call the rest of the monks in to witness this marvelous sight when a mouse stuck his head out from a little hole in the wall.

St. Martín without hesitation addressed the mouse as if he were an old friend. “Don’t be afraid, little one. If you’re hungry come and eat with the others.” The little mouse hesitated but then scampered to the bowl of soup. The friar could not speak. At the feet of the servant St. Martín, a dog, a cat, and a mouse were eating from the same bowl of soup, natural enemies eating peacefully side by side!

This “little story” of St. Martín envisions an unparalleled fellowship. As such, it refers to the “big story” of the end times as envisioned by Isaiah: “The wolf shall live with the lamb, the leopard shall lie down with the kid, the calf and the lion and the fatling together, and a little child shall lead them” (11:6).

The story also shows us the way to the kingdom of God, the entrance of those we consider stranger, exile, or lost. When we are welcomed at that door, we are no longer to fight like cats and dogs. Instead we drink from the same bowl of soup. And this bowl of soup, this new image of Eucharist, shall be for us the true meaning of communion. Opening the door to a stranger is making a space at the table of the Lord.

This is the real meaning of St. Martín’s service at the door of the monastery. In taking care of the poor and even dogs, cats, and mice, St. Martín de Porres leads us from the margins of this world’s structures into the warmth of the Lord’s table in the kingdom of God.

This article appeared in the February 2008 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 73, No. 2, pages 47-48).

This article is also available in Spanish.

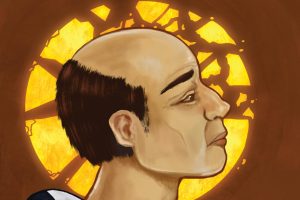

Image: AgainErick/Wiki Commons

Add comment