When I entered the confessional that day I assumed I would be absolved of whatever transgressions I chose to reveal. From what I’ve been told, Father Charles has never been known to withhold his forgiveness and mercy. He understands the frailties of human virtue. He knows about the appetites of the flesh. In fact, I’ll wager he has surrendered to a few of them himself. So I expected to be forgiven. I did not, however, expect to be pitched into a full-blown midlife crisis as penance.

Father Charles, whose last name contains no vowels so it can’t be pronounced except by first-generation Eastern Europeans, is unlike any priest I’ve ever known. Normally you might expect to find a Catholic priest in his study, poring over ancient biblical texts, chanting over incense, or polishing his chalice. If he isn’t in church, you expect to find him out and about dispensing communion to the sick and homebound, not up on the roof of the church, where Father Charles spends an inordinate amount of his time. If he isn’t up there patching leaks or reinforcing the bell tower, he is out back with a chainsaw messing with the vines and the branches, or down in the cellar where it is rumored he brews his own beer. On Saturday afternoons, though, you can expect to find him in the confessional.

For faithful Catholics who subscribe to the legitimacy of priestly absolution, preparing for confession is punishment enough. You have to stop whatever you’re doing on a Saturday afternoon—hanging out laundry, weeding the garden, or napping on the couch—to wash up and change into something presentable, not fancy but at least clean. When you get to church, you line up in the back with all the other sinners and wait your turn. This affords you plenty of time to prepare a list of your most shameful transgressions, lest you forget how bad you’ve been. And if your list isn’t long enough, suggesting that you’re too holy for words, you can always throw in a few of the old standards. Greed, jealousy, and laziness are usually high on my reserve list.

In line that day, a child fidgeted. First, she tugged at the lace-trimmed white socks that crept down into the heels of her shiny black patent leather shoes. Then she tugged at the sleeve of the cardigan she’d outgrown. She stepped out of line again and again to see if it was getting any shorter, and then she looked behind her to see if it was getting any longer. I wondered what she could possibly have done that required her to be forgiven by a priest. She cheated on her Christmas list?

Behind me old Mrs. Everhart, in her orthopedic shoes and elastic hose, clicked away on her rosary beads. I couldn’t imagine what sin might have darkened her sweet mitten-knitting, cookie-baking, porch-sweeping soul. She substituted margarine for butter in the bake sale brownies?

I’m willing to wager that on an ordinary Saturday afternoon none of us in line had raped, pillaged, or murdered anyone. Instead, we’re likely to have lost sleep over a slip of the tongue, a neglected kindness, or an unintentional snub. We get in line because we’ve been provoked to anger or envy or spite by people who are out to get us. Or because the flesh is weak. Or because we’re simply human.

So it wasn’t because of any grievous sin that I stood in line that day. I hardly ever lie or cheat, and I’d never steal. For me, self-indulgence amounts to sprinkling a few grains of salt on my Egg Beaters in the morning as long as no one is watching—and then giving thanks for it. I almost never make fun of anyone anymore, either. Well, I did roll my eyes when I saw the spandex my neighbor wore the last time she went out for a jog. Still, it annoyed me to have to confess it to a priest who’s less than perfect himself. I can’t imagine who hears his confession.

Nevertheless, when it was my turn I entered the confessional quietly and reverently, and took a seat right there in front of Father Charles. Nowadays the priest can hear your confession in broad daylight. Dark, scary confessionals are a thing of the past. This has its advantages and disadvantages. Thankfully, claustrophobia is no longer an issue. On the other hand, the old confessionals did guarantee anonymity. Now you walk in and sit down face to face with the priest so he knows exactly who it is who forgot to say grace before meals, missed Mass on Sunday, and lied to her husband about the dent in the car door. (No, I didn’t hit a deer on the way home from the grocery store. The cart rolled away while I was looking for my car keys and bam! A dent.) And he knows who it is who can’t keep her hands away from, well, you know—sinning.

As soon as I took my seat, Father Charles nodded and smiled as though we were meeting for tea and cookies. “It’s good to see you, Laura,” he said. “I’m glad you came in,” meaning it’s about time you got your poor pathetic soul in here. “How have you been?” meaning, how bad have you been?

I told him about the bitter, greedy, jealous thoughts I’d harbored. I told him about the slips of tongue and the four-letter words that followed. I confessed to being impatient and unkind. I told him that my husband was seeing another woman, and the kids were taking it out on me, and that was why I’d been so angry, so impatient and unkind, so jealous. I cried when I told him how hard it was to keep going, and how I’d all but given up trying.

When I finished, Father Charles admonished me, “Laura, there are times in life when it’s hard to be good”—and I thought he would stop with that, but then he went on—“to yourself. You have every right to be angry. You deserve something better. Find something that brings you peace. Do something nice for yourself.”

And that was my penance. He didn’t assign me a single Hail Mary or Our Father. He didn’t lecture me about yokes and burdens. He told me to be good to myself—not to my wayward husband or defiant children. Not to the dog who is unconditionally good to me. He didn’t insist that I be kind and considerate to my nagging mother-in-law or my nosy neighbors. He told me to be kind to myself. The problem was he didn’t tell me how.

The sun was setting as I left the church that afternoon. The bare branches of the oaks in the churchyard stretched and swayed against a bank of angry gray clouds. A veil of golden sunlight lit up the horizon. As I leaned into the wind, I contemplated a just punishment for myself.

It occurred to me that a sunny Mediterranean cruise might be just the thing—though I hadn’t forsaken God completely, so maybe that was a bit overindulgent.

I thought about a makeover or a new wardrobe, but I hadn’t committed adultery or even coveted another man, so what use was that?

Perhaps a month away at a beachside resort would do the trick, but I hadn’t stolen anything or lied about it to anyone, so that was clearly more punishment than I deserved.

I braced myself against the cold and decided that, for all the evil I had invited into my life, nothing less than a mug of steaming cappuccino topped with real whipped cream and a smidgeon of cinnamon would do. Add to that a fresh blueberry scone, warm from the oven with soft, sweet butter. The sun faded into dusk as I turned and stepped into the Hug-a-Mug Café to cleanse myself of my sins.

This short story appeared in the August 2014 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 79, No. 8, pages 37-38).

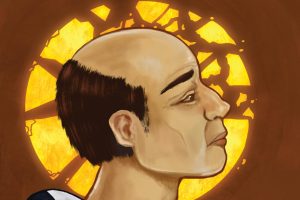

Image: Angela Cox

Add comment