Anyone who survives the dentist's drill should be able to pass this acid test. As I sit terrified in a car crammed with 15-year-old boys, my own at the wheel, I wonder, "Where is God now?" Rush hour traffic bolts feverishly, my stomach wrenches, my neck stiffens, rigid with tension. Acid rock on the radio fills the car with whining, shrieking dissonance. If Dante had had a teenaged driver, he surely would've added this trip to his circles of hell.

All around me, solitary business types in somber suits are commuting to work. In the crystalline stillness of their cars, they probably plan the day's projects and compose themselves serenely for the office. What devilish punishment has consigned me to going the opposite way, an hour round-trip away from my office? Worse, what has reduced me to such quivering stress that I will arrive there needing Valium, before any work crises have had a chance to develop? The answer is contained in my barely intelligible mutter to the concerned receptionist when I arrive, "I have a teenaged driver."

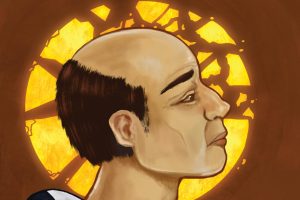

Surely those five magic words, mumbled at death's door, will compensate abundantly for all the evils I've ever committed. Saint Peter (whose teenager probably careened in a mean chariot or raced the fishing boat against Andrew's kid) will embrace me sympathetically and whisk me right past purgatory. "Ah, yes, dear. We understand," he'll cluck soothingly. The angels will gather in empathy and stroke my contorted spine with feathery tenderness. The martyrs will recognize one of their own, a bold, kindred spirit who risked the freeway at 8 a.m. As cherubim inquire about the newcomer, they nod knowingly and pull out a special throne: deep and cushiony, on heaven's highest porch, with a sweeping view of spectacular sunsets and a steady stream of mai tais-yeah, with little paper umbrellas! Then comes the moment when grace rushes in. Despite all my efforts to bring God into the car pool, I love the moment when it empties. With the car all to myself, I dial the radio to the soft liquid of classical music. I reclaim my thoughts-and my wheel. "Heh, heh," I chortle, crazed with power. "I'm in the driver's seat!" It's an exhilaration that the childless never sense as they slip blithely behind the wheels of their cars. Poor folks-they're always in charge. They miss the joyful ebb and flow of surrendering control and regaining it. Nor will they ever celebrate a safe arrival with the heartfelt gratitude of the licensed driver who sits beside the driver's permit. Whenever I see a picture of the pope deplaning and kissing the ground of a foreign country, I think, "Yup, that's the relief I feel." If it weren't so grubby, I might start kissing the floor of my garage.

Trapped in this picnic-bench cage, I try desperately to concoct conversational ploys. "Well, they'll grow out of it" doesn't seem to cut it for football quarterbacks who lurch beside doll-sized moms. The only decent solution seems to be to admit one's abysmal sin in this public confessional and genuflect abjectly before the teacher with profuse apologies and firm promises of amendment. Then exit as gracefully as possible, saving for the parking lot the sanctions upon the son who's lassoed us into this predicament.

As usual, the understandings don't seem to come until sufficient time, that gracious restorer of perspective, has elapsed. In this case, we're talking lots of time spread over four children.

The sad truth is that for folks supposedly in the know, professional teachers and writers, we have a dismal history of faithful attendance at conferences for the parenting-impaired. Yup, we know the latest educational trends; we read the journals; we attend the conventions and keep up the credentials. But somehow we can't hold a candle to the wonderful janitor down the block whose kid gets straight As and a full ride through college. Our frequent trips through cafeteria-table hell are tributes to God's sense of humor and our increasing sense of humility.

But most important of all, this insidious form of torture gives me a glimpse into a quality of Jesus that I call "sad tiredness." It surfaces repeatedly as disciple after disciple demonstrates how sweepingly they have misunderstood him. That catch in his voice, that hesitation in his heart rings familiar to the survivor of the cafeteria conference.

We hear it when James and John request thrones on his right and left. It echoes again when Peter warns him blatantly that talk about justice will get him in trouble. Philip seems to be a perpetual teenager who asks the perennial stupid question. Jesus addresses him with parental weariness, "Have I been with you all this time, Philip, and you still do not know me?" (John 14:9). As the disciples jostle for favors, wish audibly for the perks, and theorize about their power in the kingdom, we can almost hear Jesus whisper, "How could you have gotten it so wrong?"

To the arrogant teenager we long to say, "Everything I value I've tried to pass on to you, and you have set it aside." The same perplexity echoes through the scriptural story of the unfruitful vineyard. It details all the gifts God has carefully provided to nurture a vineyard, which in turn produces only wild grapes. With all natural expectations dashed, God asks the answerable question: "What more was there to do for my vineyard that I have not done in it?" (Isa. 5:4). We have not been the perfect parents, but when our children disappoint us, we begin to understand how our own failures must sadden God.

Yet the stunning mystery quivering at the heart of all this is that despite the disappointment or even the broken heart, we continue to love the errant child. At the moment we are closest to strangling him or her, we would also hurl our bodies in front of anyone who threatened that precious life.

We maybe moan the terrible study habits, the blithe disregard for an education that is costing us a fortune-but God help anyone else who criticizes! Deep down, we love that child with an aching ferocity. We value that life more than our own. In the paradox, we glimpse a God heartbroken over our inadequacies yet, at the same time, sending the most precious Son to redeem us.

Until I had children, I could never hold such polarities in tension; the two ideas could not coexist in my mind. Now I see how what I despair of most completely is also what I most deeply cherish.

Biblically, it's a common thread, where parents and God and sons seem to take interchangeable roles. As the parable father peers far down the dusty road, yearning for the son who squandered the inheritance, the stance is familiar. It isn't the rabbi who welcomes the son home, just as it isn't his apostles, but his mother who prompts Jesus' first miracle.

Only the parent-child relationship, it seems, is woven close enough to bear the weight of the ultimate truths. Familiarity may breed contempt, but the round contours and smoothed edges of home also create a relaxed state where the guard is down and the understanding can occur. A cluster of similar biblical stories resonates with a message learned better in the household than in the temple: don't waste energy on the mistake, the grade, the failure; celebrate instead the son come home.

Conference time is also prime time to recall our own offenses. Only through those did we ourselves learn how God, greater than any hurt, can forgive any wrong. Back in grade school, long before parenthood, I couldn't understand why a God as great as ours is purported to be could love a creature so prone to failure as myself. Parenthood provided an insider's look at that question.

Didn't I fall in love, hopelessly, immediately, and forever, with a tiny being still streaked with blood, whose birth had caused me considerable pain and whose presence promised to interrupt my sleep and drain my bank account for years ahead? Was God's loving me any more logical? As Thomas More explains to his son-in-law William Roper in the film "A Man for All Seasons," "Finally, it's not a matter for reason. Finally it's a matter of love."

I will learn to endure the parent-teacher conferences, a powerful learning experience. There we know that we are like God when we give our hearts into such small hands, then live out a commitment which can carry a staggering cost.

The saga of the pink suit

It was outrageously expensive and wildly impractical. Even the most sympathetic male would find it hard to understand why I coveted it. The pink suit also fit like a glove and was stunningly beautiful. My older daughter, Colleen, and I stumbled upon it during one of our shopping trips meant to find her a swimsuit or a pair of jeans. Inevitably, when we set out with such a definite daughter agenda, we wound up finding treasures for Mom.

Graciously, Colleen would then assume the role of fashion consultant, giving me a critical reading on every garment I tried. One look at her face was enough to tell me if a new outfit rated further consideration. Her eyes lit up when I tried on the pink suit. But after long consideration of the price, the necessity of dry cleaning, the limited number of occasions on which I could wear it, we decided to return it (reluctantly) to the rack and concentrate on more practical purchases.

For someone to make such imaginative leaps from the ordinary requires a jumping-off place, some foretaste, some glimpse of the shimmering satin. To then appropriate the image to oneself, one must have a deeply rooted sense of what all humans justly deserve: the natural dignity that befits every son or daughter of God. The appearance is deceptive, says such a stance. We may not be costumed for the part, but beneath the misleading surface, we are indeed the children of the most high king.

Perhaps it is a far reach from seeds to pink suits. But even pampered people in modern homes need a glimmer of grace, a reminder of our high calling. We need our diamond from the king's crown, even if it's only a drop of dew on a pansy's velvet surface or the costume jewelry inherited from a beloved relative. We may be surrounded by material comforts, but still we seem to need frequent reminders of who we are.

As if to prove that theory, I regularly endure a moment of panic before every public speaking engagement. About five minutes before I'm slated to go on stage, I blank on content, lose any concept of why I'm doing this, and wonder how fast I can find the nearest exit. At that time,I usually vanish into the ladies' room for a few deep breaths and the kind of urgent prayer that drowning people must say as the waters fill their lungs. Then I emerge from the rest room with confidence restored and energy renewed. "Bring on the audience!" I want to shout, lunging toward the podium.

For the next few talks, I have a new weapon in the preparation arsenal. I'll enter the ladies' room and look in the mirror. It will gleam back at me in stunning pink: wildly impractical, outrageously expensive. I will stroke its soft skirt and remember a day at the dentist, a little girl who once put in her time in the dentist's chair, too, and a mature girl's thoughtfulness that every parent deserves at least once.

The audience will not know the saga, nor guess that something pink's at play. But perhaps with enthusiasm and conviction, I can remind them that they, too, are bejeweled; they, too, are children of the king who clothes them in luxury and extravagance, who attaches no price and no strings to the gifts showered on beloved children.

Add comment