What do gangsters and ballerinas have in common? A deadly drive, according to the latest dance thriller Black Swan.

Black Swan is a movie about the ballet in the same way The Godfather is a film about the family business. Like Francis Ford Coppola’s tragic tale of Michael Corleone’s descent into slaughter, Darren Aronofsky’s seemingly arthouse film about ballet is a movie about what drives the American family business—ambition—and about the biblical costs we pay in pursuit of dreams of success.

Aronofsky’s deeply unsettling melodrama about the slow, shattering self-destruction of a young ballerina who dreams of dancing the lead role in Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake highlights the staggering costs of the single-minded pursuit of success so widely admired and encouraged by American audiences and parents.

After years of dancing small parts in a Lincoln Center ballet company, Nina Sayers (Natalie Portman) is cast to play both the virtuous White Swan and her evil doppelgänger sister in what is to be a radical and visceral reworking of Tchaikovsky’s masterpiece.

But Thomas (Vincent Cassel), the company’s artistic director, complains that Nina’s technical perfection as a dancer is matched with an emotional sterility that renders her Black Swan flat and sexless. So he badgers and berates her, trying to provoke dark and sexual passions that will electrify her performance; and when this fails he threatens her with a competitor, Lily (Mila Kunis), whose lusty earthiness makes her the perfect opponent to Nina’s frigid innocence.

And this threat drives Nina towards madness, pushing her back into self-destructive cutting and bulimic vomiting, and inflaming paranoid and violent delusions. In spite of her technical perfection and staggering commitment, Nina is a frail child, an innocent preteen trapped in the emaciated body of a woman.

Like a stunted fairy princess, she lives in a small, cramped apartment with her sweetly protective and savagely domineering mother, Erica (Barbara Hershey), and has no emotional or sexual life of her own. Compared with Lily, who radiates a wild and experienced sensuality, Nina is a hothouse flower that has never blossomed.

Thomas believes Nina’s frigidity and sexual innocence is the stumbling block that keeps her from being a great dancer, and he sets her up against both Lily and his former lead dancer Beth (Winona Ryder), women whose passion and sexuality flame out in distinctively uncontrolled ways.

In Aronofsky’s film Nina’s innocence is indeed the problem, but not in the way Thomas imagines. For while the movie presents Nina as a fragile innocent let loose among a host of vicious competitors, and while Nina, Erica, and Thomas conspire to protect this fiction in a variety of different ways, the truth is that no one succeeds in the ruthless competition of professional ballet without a steel core of ambition that would hold up the Brooklyn Bridge. A delicate flower cannot withstand the emotional and physical agony that make up the daily routine of professional ballet, tolerate the rejection, or succeed against a firestorm of competitors hungry to steal your shoes and role. Wilting wallflowers are not handed lead roles or an armful of roses.

Frail Nina dreams of replacing (and killing) Beth and is ready to let loose the same violence on Lily and any other competitor. She fantasizes about breaking out of the pack and climbing to the top, where she will have her own star, dressing room, and throne. She is as nakedly ambitious as Michael Corleone, and—like him—as unconscious of that ambition. Compared to her, Lily and Beth are a lackluster pair of Survivor wannabes.

But Nina must hide this ambition from herself, masking a ruthless and competitive spirit behind a veil of childlike innocence, the same way Corleone spends the first half of The Godfather telling himself and his fiancé that he is not like his murderous and criminal family. The second half proves that his ambition and violence exceeds that of his father or brother.

As we get to know Nina we discover that her memory and self-image are not so reliable. She is capable of more than she thinks. And when Erica protests that she only wants what is good for her little girl, we catch a glimpse of a steely Nina who knows the lie of such protests and possesses an ambition that will leave her keeper in the dust.

Thomas thinks Nina cannot dance the Black Swan because of her emotional and sexual innocence, but Aronofsky hints she will dance a savage performance because her innocence masks a ruthless ambition she cannot acknowledge, an ambition that drives her to endure and embrace unimaginable suffering. Unfortunately, this innocence also masks and justifies a madness that is ultimately self-destructive.

The emotional and physical violence unleashed in Black Swan is like the bloodbath at the end of The Godfather. In both films a veil of innocence masks the ambition of the protagonists, an ambition that turns to wrath when challenged or frustrated.

Both Nina and Michael are desperate to hide their unsavory ambition and to deny responsibility for the carnage it leaves in its wake. Michael orders brutal murders under the sacramental cover of his child’s baptism, while Nina convinces herself and others that she lacks the passion to play the very creature she has needed to be all along just to get this role.

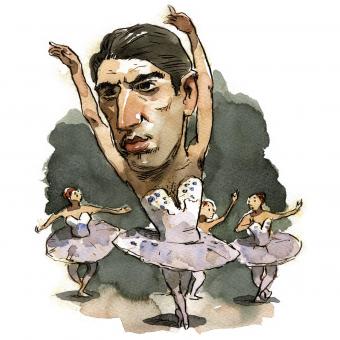

Some suggest Aronofsky’s film uncovers the awful price we pay for perfection. But even more, Black Swan has taken a long, hard look at that most American of passions—ambition—and uncovered the way we try to hide and mask the naked violence of that ambition in something pretty, sweet, and innocent. Nina is a young Michael Corleone in a tutu, dressed up as a lovely ballerina, and wearing the makeup of an ingénue; but in the end she is still Michael Corleone, and ambition is still murder.

This article appeared in the April 2011 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 76, No. 4, pages 40-41).

Image: Darren Thompson

Add comment