“Modern spiritual classics” recommended by Kathleen Norris, Martin E. Marty, Joyce Rupp, Joan Chittister, and other prominent U.S. Catholic contributors

Spiritual seekers have long looked to free their souls in written wisdom, but those hoping to climb the heights today might find themselves buried under a pile of books at the nearest Barnes and Noble. From The Secret (Atria) to The Purpose-Driven Life (Zondervan) to the latest selection from the queen of daytime television, it can be hard to discern the diamonds from the dross.

Who is today's St. Augustine, whose fifth-century spiritual autobiography, Confessions, is still in paperback? Who can wield a pen with the likes of Julian of Norwich or St. Teresa of Ávila? Will any of the current crop of gurus survive the next decade, much less the next century?

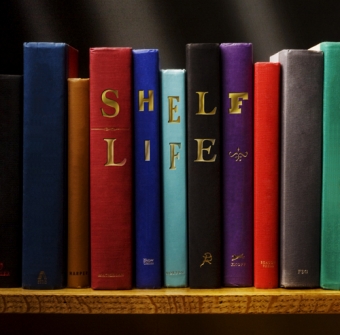

We at U.S. Catholic asked some of our long-time contributors-award winners, theologians, activists, scientists, and writers of classics themselves-to choose a work that may indeed feed souls for generations. What they picked-from fiction to film, poetry to peacemaking-may surprise you. And though you won't likely find the nine works reviewed here on Oprah's next list, we hope that you may at least discover a new addition to your spiritual bookshelf.

Selected Poems

Selected Poems

By Denise Levertov (New Directions, 2002)

Denise Levertov's work surely stands as a spiritual classic for our time. Levertov had a lifelong commitment to social justice and a gift for writing about both politics and faith in a way that did not stifle her poetic gifts.

Scriptural allusions abound in her early poems-"O Taste and See," "The Jacob's Ladder"-but beginning in the 1980s, Levertov's work openly reflected her rediscovered Christian faith. In a 1990 essay, "Work that Enfaiths," she describes envisioning a long poem, a "Mass for the Day of St. Thomas Didymus," as a "secular meditation," much as musical composers have done for centuries. By the time she was working on the Agnus Dei she discovered that "the experience of writing the poem-that long swim through waters of unknown depth-had been also a conversion process."

Levertov's struggles with doubt and aversion to institutional religion will resonate with many, who might also value the way she grounds her poetry about faith in the natural world. "The Mountain's Daily Speech is Silence" is the title of one poem. And "Flickering Mind," which begins, "Lord, not you, / it is I who am absent," is a primer on what it means to pray.

In a 1984 essay, "A Poet's View," Levertov addresses head-on her gradual moving from a "regretful skepticism" to "a position of Christian belief," her increased willingness to adopt the rituals of the church in the hope that faith might follow, "and with it some way to deal intellectually with…troublesome mysteries and paradoxes."

The fruits of her endeavor are evident in the richness of her poetry from this period. In "Annunciation" she yanks the biblical story off the page and puts it squarely inside the reader's life, asking, "Aren't there annunciations/of one sort or another/in most lives?"

Reviewed by Kathleen Norris, whose most recent book is Acedia & Me: A Marriage, Monks, and a Writer's Life (Riverhead, 2008).

Compassion: Listening to the Cries of the World

Compassion: Listening to the Cries of the World

By Christina Feldman (Rodmell Press, 2005)

Is there a virtue more indispensable in our world today than that of compassion? I doubt it. Browse through local and world news. Much of it reveals the necessity of compassion for both personal and world transformation.

My first influential encounter with this quality began in 1982 with Compassion by Donald McNeill, Douglas Morrison, and Henri Nouwen (Image). Their presentation of Jesus as the embodiment of the "God of compassion" both inspired and challenged me.

Ever since then I've felt drawn to embrace and live this gospel quality. Consequently, I've read and studied numerous books on the topic. But not until I came across Christina Feldman's Compassion: Listening to the Cries of the World, did I feel so motivated.

Although Feldman's style is non-academic, her work breathes foundational depth. In eight short chapters she urges the reader to reflect on the components of compassion "for ourselves, the blameless, those who cause suffering, those we love, and those in adversity." She consistently inspires and challenges her readers to live compassionately not by offering guilt-ridden "shoulds" but by clear, concise statements, such as the following:

"Compassion speaks of the willingness to engage with tragedy, loss, and pain. Its domain is not only the world of those you love and care for, but equally the people who threaten you, the countless people you don't know, the homeless person on the street, and the situations of anger and hatred you recoil from. It is here that you learn about the depths of tolerance and understanding that are possible for each one of us. It is here that you learn about dignity, meaning, and greatness of heart."

This book, written by a Buddhist dedicated to living compassionately for four decades, contains immense potential for rousing the reader toward living the central quality in the life and teachings of Jesus. It belongs on every Christian bookshelf.

Reviewed by Joyce Rupp, a Servite Sister, spiritual guide, international speaker, retreat facilitator, and author of Open the Door: A Journey to the True Self (Sorin, 2008), which is available at joycerupp.com.

Life Together

Life Together

By Dietrich Bonhoeffer (HarperOne, 1939, 1954, 1978)

My "modern spiritual classic" is Dietrich Bonhoeffer's Life Together. The story of this little book is so dramatic that telling it in detail might distract from its stunningly simple contents.

The story: When Hitler came to power in Germany, the Gestapo put priests and ministers on its "to be watched" list. As resistance grew among the too-few protesters, "watching" turned to snooping, limiting, eventually arresting, and finally executing the dissidents, as in Bonhoeffer's own case.

When the official churches and seminaries were taken over by Nazis and their stooges, courageous evangelical Protestants formed a gutsy "Confessing Church," which stood up for Jews and the Christian gospel. A score and more seminarians fled to Finkenwalde, an almost hidden estate in the dunes near the North Sea. A few landowners who loved theology and admired the seminarians provided housing and classroom space.

The leader was 30-year-old Dietrich Bonhoeffer. By then he had written a fashionably pretentious doctoral dissertation, had been to Rome, Barcelona, New York, Cuba, and Mexico, and even served a German church in London. But in 1935 he was needed to teach and to lead.

In Life Together none of the turgid style designed to impress Bonhoeffer's theological professors remains. This book, not a record of Finkenwalde life but a book of celebration and counsel that reflects his experience there, has much to say to Christians everywhere today. It was used during church struggles in South Africa and would be a profitable read for church struggles and soul struggles in North America.

To the point: In our culture "everyone" loves Jesus and wants to be "spiritual," but often in isolation. Life Together speaks to the heart, showing why self-directed spirituality is self-serving and self-defeating. Bonhoeffer's illegal seminarians made a great point of being grounded in and related to the community, the suffering and messy church. In italics he warned: "Let him who cannot be alone beware of community. Let him who is not in community beware of being alone." We've been warned-and inspired.

Reviewed by Martin E. Marty, Fairfax M. Cone Distinguished Service Professor Emeritus at the University of Chicago and an ordained Lutheran minister.

Resurrection Song: African American Spirituality

Resurrection Song: African American Spirituality

By Flora Wilson Bridges (Orbis, 2001)

Religion and spirituality are often seen as interchangeable terms but they are not. Flora Wilson Bridges, in her excellent study of African American spirituality, Resurrection Song, firmly corrects this misunderstanding. She notes that religion is a more structured concept that relates to rites, rituals, and creeds, while spirituality is a much broader term that addresses an individual's or community's experience of and response to God. Putting it bluntly, in the Black community, it is "defined as whether one knows Jesus."

Bridges responds to the critique of many Black theologians for ignoring spirituality and paying more attention to sociological, economic, and political issues instead. Her in-depth analysis begins in the motherland of Africa to reveal the critical roots of contemporary Black spirituality in the United States today. She traces the holistic worldview of African peoples and explores how that spirituality was grafted onto the tree of African American culture and life by retention of sayings, music, stories, and songs, to create a new yet old spirituality.

Seeing spirituality as a "way of being" rather than just a "way of knowing," Bridges reveals how spirituality is at the very heart of the African American experience in the United States, an experience of forced migration, slavery, racial prejudice, and second-class citizenship. It is this spirituality that sustained and nurtured those enslaved, enabling them to preserve much of the past while forging new identities in the cruel new world in which they found themselves.

This work fills a serious gap in our understanding of how Africans became African Americans. It reveals the spiritual matrix from which the Black church and Black leaders emerged. It can also serve as a guide for the "return" that is needed in the Black community today, a return to the faith and spirit of our foremothers and forefathers that is in danger of being lost.

Reviewed by Diana L. Hayes, a professor of systematic theology at Georgetown University.

No Bars to Manhood

No Bars to Manhood

By Daniel Berrigan (Doubleday, 1970)

These days, we're facing the U.S. wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, new nuclear weapons production, global economic collapse, climate disruption, and poverty on an unprecedented scale. Great spiritual books, I think, should help us in the work of abolishing war, poverty, nuclear weapons, and global warming. They should inspire us to follow the nonviolent Jesus, all the way to the cross, the new life of resurrection, and God's reign of peace.

Daniel Berrigan recently turned 87 and continues to publish books of poetry, essays, and scripture commentary. The legendary Jesuit has spent his life teaching peace, and many of his books could qualify as "spiritual classics."

Berrigan's 1970 collection of essays, No Bars to Manhood, sums up his life journey and the journey of the postmodern Catholic Christian disciple. The book models for us how to undertake our own journey of gospel nonviolence, to stand against the culture of war, and to witness to the God of peace.

"We have assumed the name of peacemakers," Berrigan wrote here long ago, "but we have been, by and large, unwilling to pay any significant price….There is no peace because there are no peacemakers. There are no makers of peace because the making of peace is at least as costly as the making of war, at least as exigent, at least as disruptive, at least as liable to bring disgrace and prison and death in its wake."

No Bars to Manhood features a long autobiographical account of Dan's journey to peace, several essays on his Catonsville Nine action, and critiques of war-making America. But that is just the beginning. There are reflections on the books of Jeremiah and Revelation, St. Paul and Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Gandhi and Albert Camus.

Happily, No Bars to Manhood was reprinted last year by Wipf and Stock, and I urge readers to get a new copy and learn a few lessons from a steadfast nonviolent resister. We're going to need them for the years ahead.

Reviewed by John Dear, S.J., who was recently nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize by Archbishop Desmond Tutu. His autobiography, A Persistent Peace (persistentpeace.com), has just been published by Loyola Press.

Song of Solomon

Song of Solomon

By Toni Morrison (Knopf, 1977)

Afew months after my father died in the summer of 1978, my mother went into the hospital to have a large tumor removed from her left shoulder. The tumor had grown increasingly painful since its first appearance 25 years earlier, up to the year before my father finally became exhausted from the cancer that had inhabited him for 12 years.

The night before she went into the hospital, I gave her a copy of Song of Solomon because I knew she would love the book, filled as it was with characters she would recognize and situations she would devour.

How could she not love it? Old women sang prophetic songs, conversed with their long-dead fathers, and dreamed of the destruction of the institutions of racism. Little boys who dreamed of flying but were crippled by the realities of commerce held fast to the earth because they could not dream at all. Young women searched for connections and words of liberation.

The book was filled with questions: of family, of the real and the supernatural, of grace and obsessive lusts for power, advantage, and certainty. And it bore the greatest question of all: What is the true cost of love and the price we pay if we are afraid to love?

Song of Solomon's central figure does not want to hear the stories of the past and crawls to a hillside in Virginia, where he learns his true name and has a revelation as cataclysmic as that of St. John the Divine. When one learns to love, to accept, to nurture, and to caress the truth of another, one can gain the power to fly.

My mother came out of the surgery and told me that she read the whole book in that one night.

Reviewed by Joseph Brown, S.J., professor and director of the Black American Studies program at Southern Illinois University in Carbondale, Illinois.

![]() Praying with Icons

Praying with Icons

By Jim Forest (Orbis, 1997, 2008)

As the world gets smaller, it is not enough simply to concentrate on the physical dimensions of a world that now stretches our consciousness beyond the local. Being able to find Novgorod or Vladimir on a map is not enough to satisfy the need to understand the people of another place. There are better ways to do that than simply studying geography: travel, art, music, literature, religion, for instance. And even better than such isolated approaches, perhaps, the art of a religion.

Jim Forest's revised Praying with Icons does just that. It blends the two to make a bridge between West and East. By using the art of iconography, Forest gives us a privileged glimpse into the splendors of Orthodox Christianity.

More than simply describing icons, Forest enables the Western Christian to understand even better the spiritual perspectives that enkindle the religious art of the Orthodox Christian, both here and abroad.

The text gives us a fresh look at our own stories, symbols, and theological customs by discovering what we each emphasize. By recognizing the theological weight of what we don't see in an icon, we broaden our own insights into the image. Just as iconographers, in the language of the art, "write" an icon, Forest teaches us how to read one. In his hands icons become a lectio divina, a holy reading, of color.

While Forest introduces us to the art of iconography, its process, and symbol systems, he goes further. He explains the Orthodox theology the art implies. He points out, for instance, that in the Orthodox icon of the holy supper, Jesus does not sit at the head or even the center of the table, as he does in classic Western depictions. "Jesus' place at the table," he points out, "is not top center, as one might expect, but-emphasizing his choice not to rule but to serve-on the upper left of a circular table around which the twelve are seated."

The book is an excursion through the faith from the point of view of the Eastern church. It is one that enriches our own and binds East and West closer and closer as one church at the same time. We will need a book such as this for a long, long time in this changing world.

Reviewed by Sister Joan Chittister, O.S.B., an international lecturer and co-chair of the Global Peace Initiative of Women, a U.N.-sponsored organization working for worldwide peace and justice. She is author of the book The Gift of Years (Bluebridge, 2008).

Stop Making Sense

Stop Making Sense

By The Talking Heads (Palm Pictures, 1984, 1999)

Spiritual classics are inspirational works, tested by time, designed to bring one closer to God. G.K. Chesterton and John Henry Newman come to mind. I have works on my shelf by modern religious writers, from Peter Kreeft to Anne Lamott, who manage to inspire me-when I am not furiously disagreeing with them. But my soul's deepest stirring comes from a source neither literary nor overtly religious.

Music inspired humans before we could speak, I suspect. Movies are a more recent yet wildly popular medium. Combining the two gives a doubly powerful route into our souls.

The Talking Heads were not a band of my youth. I was well into my 30s when their concert film Stop Making Sense, directed by Jonathan Demme, came out. It combines music you can dance to with lyrics that recapitulate the boomer experience of rebellion, idealism, and subsequent cynicism-all leading to that mysterious moment when you find yourself suddenly an adult, with a vocation and responsibilities, asking, "How did I get here?" (The lyric is from "Once in a Lifetime," the film's climactic moment.)

By the end of the film they're covering the Al Green/Teenie Hodges standard "Take Me to the River." The typical love song's comparison of first love to a religious experience has been flipped into a religious experience as powerful as first love.

More than 20 years later, I find the music both chillingly prophetic ("Life During Wartime") and filled with religious imagery that once went right past me. It forces me to remember where I have been, and to ask the questions: Where am I? How did I get here?

Reviewed by Guy Consolmagno, S.J., curator of meteorites at the Vatican Observatory. His most recent book is God's Mechanics (Jossey-Bass, 2008).

Thirst

Thirst

Poems by Mary Oliver (Beacon Press, 2006)

Another morning and I wake with thirst for the goodness I do not have. I walk out to the pond and all the way God has given us such beautiful lessons. Oh Lord, I was never a quick scholar but sulked and hunched over my books past the hour and the bell; grant me, in your mercy, a little more time. Love for the earth and love for you are having such a long conversation in my heart. Who knows what will finally happen or where I will be sent, yet already I have given a great many things away, expecting to be told to pack nothing, except the prayers which, with this thirst, I am slowly learning.

-Epilogue

In Thirst, a book of poems, Mary Oliver shares the beautiful lessons she has learned from nature, her relationships, and the death of a close friend. Her poem "Praying" confirms an unconventional learning style:

It doesn't have to be

the blue iris, it could be

weeds in a vacant lot, or a few

small stones; just

pay attention, then patch

a few words together and don't try

to make them elaborate, this isn't

a contest but the doorway

into thanks, and a silence in which

another voice may speak.

Oliver offers multiple expressions of thanks and gratitude. She is grateful for (as the titles of her poems indicate) the Museum of Fine Arts, Music, the Snake, Roses, the Otter, Seasons, the Striped Sparrow, Percy (her dog), Grieving and Sorrow, and the Creator of All.

Her poems illustrate the words of Meister Eckhart: "If the only prayer you say in your life is thank you, that would suffice." Did Mary Oliver intend to give the reader a book of poetry, a book of prayer, or both?

Pondering Oliver's poetry feels like standing in "the doorway into thanks," anticipating and awaiting the voice of the Other. Some "One" is here, there, and everywhere, knows our deepest thirst, and not only satisfies that thirst but awakens deeper desire for communion, depth, and love.

Oliver phrases our poignant thirst in the poem "What I Said at Her Service."

When we pray to love God perfectly,

surely we do not mean only.

(Lord, see how well I have done.)

The first line of the first poem frames this book, and Mary Oliver's attitude toward life: "My work is loving the world." I return to the book to be reminded of this call to "love the world."

Reviewed by Teresita Weind, S.N.D. de N., provincial of the Ohio Province of the Sisters of Notre Dame de Namur.

Add comment