Jesus has his normally crowded itinerary this month. In our Sunday readings he’ll be lecturing his disciples on why they don’t need more faith—they just need faith. Then he’ll be chased by 10 lepers crying out for a miracle. After dispatching them whole, if not unanimously grateful, he’ll teach a lesson or two about the importance of prayer. Then that needy tax collector Zacchaeus, dangling from a tree, will catch his attention.

Is this how it was? Do the gospels provide us with an accurate picture of Jesus’ ministry? If not a diary of his work, what do these stories offer? And how do we know what we know?

Biblical scholars labor to explain what we’re reading in Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. The gospels, they remind us, aren’t journalism. They don’t provide the breaking news cycle of what Jesus said and did in real time.

None of the evangelists were there, frankly—even Matthew and John, named among the Twelve, didn’t write the texts that bear their names. Ancient bishops, centuries closer to the scene than we are, record that Matthew the apostle compiled sayings of Jesus. Matthew the gospel may include that resource, but as much as 45 percent of Matthew comes from the earlier Mark. John’s gospel, written near the end of the first century, may contain traditions from that apostle but was written by the community that remembered him later on.

As for Mark and Luke, both came into the story at the time of Paul, who himself encountered the Lord only once on the Damascus road. If you want real-time reporting, Paul’s letters are as close to the action as you can get. Unfortunately, Paul is rarely interested in the action, so preoccupied is he with its theological implications.

If the gospels aren’t journalism, what are they? Not biography, certainly. In ancient times, biography was an established literary form. Biographies, then as now, were exceptionally thorough. The gospels are painfully thin by comparison and don’t pretend to present the story of Jesus. Only two even mention his birth, and apart from a single adolescent episode, launch directly into the final year of his life. John’s account alone implies a three-year ministry for Jesus. But even so, three years is hardly the whole story.

Proportionately speaking, the gospels provide a better sense of the death of Jesus than they do of his life. One quarter to one third of the chapters, depending on the account, concerns the week before his execution. It defies the definition of biography to call such a lopsided report by the name. The gospels are clearly something else.

Above all else, the gospel is testimony: an article of faith, a challenge to decide for or against its contents. As testimony it’s selective, providing what’s vital and leaving plenty unsaid. John’s gospel admits that much more could be written about Jesus— but wasn’t. We have what we have. So how do we understand this inheritance?

Scholars point to five criteria for evaluating these accounts from the perspective of history. These criteria don’t prove anything to be unhistorical; quite the opposite, their purpose is to verify what’s probable. History, remember, isn’t the ultimate criteria by which scripture values truth. But history is important to us because we’re in it. It’s where we draw closer to the humanity of Jesus. Before we make our decision about Jesus the Christ, we must first encounter, as every believer once did, Jesus the man.

So here’s the first criterion for uncovering the historical Jesus, and it’s surprising: embarrassment. If a thing is embarrassing, it probably happened. Consider your own self-presentation. You do your best to look good: You wash your face, comb your hair, wear decent clothes, watch your language. When you talk about yourself, you try to omit the less-than-flattering details. But if something isn’t nice and can’t be hidden and must be told, then it’s better if you do it before those less friendly to you get a crack at their version.

Embarrassing ideas in the gospels can be taken salt-free, as it were. For example: Jesus was chased out of his hometown when he preached there. Jesus said he didn’t know the day or hour of final judgment, and he originally imagined his mission as restricted to the lost sheep of the house of Israel. He chose 12 associates, one of whom turned traitor. His appointed successor denied he knew him.

All his friends asked dumb questions that revealed their obtuseness. Seats of honor and glory preoccupied their ambition. Jesus was rejected by religious leaders and executed by the state in the humiliating way that slaves and murderers were put to death. Then everyone ran away. No true believer would include these details unless they had to.

The second criterion scholars use as a historical yardstick is dissimilarity. If no one else was doing it, then it probably started with Jesus. Here we find unusual things: Jesus prohibited the taking of oaths—let your yes be yes and your no be no—among people who took oaths routinely. Jesus’ gang was called a bunch of gluttons and drunkards at a time when holy folk were marked by severity and fasting.

Jesus said, “Let the dead bury their dead,” to a community that deemed burying the dead a sacred obligation. Jesus called God Abba, “my own dear Father,” which seems innocent since the whole nation claimed God as Father. But no one person could make that claim for himself.

Perhaps the strangest thing Jesus did was to start a sentence with “Amen.” The Hebrew word ratifies what’s been spoken, as at the end of a prayer: “So be it. Amen.” But Jesus ratified his own statements before he even made them!

The third criterion is multiple sources. Obviously anything that appears in four gospels holds greater confidence than the report of one. Something attested in the gospels and the letters of Paul, written earlier, is even more reliable. So the multiplication of loaves and fishes, included in John’s late report, affirms the often unified voice of Mark, Matthew, and Luke in their description. Similarly, Paul’s account of Jesus’ words at the Last Supper is echoed by three later gospels.

Consistency is the fourth criterion. This element featured strongly in forming the scriptural canon to begin with. Consider: If nine friends say Bob is generous and one says Bob is stingy, you might wonder if that 10th fellow is to be trusted.

Lots of manuscripts floated around the ancient world purporting to include testimony about Jesus. Some of them told stories that sure don’t sound like the Jesus we know and love. If it’s too “out there,” it stays out there. That’s why gospels written under the names of Thomas, Peter, Judas, and others didn’t make the final cut.

The final criterion is rejection. The one thing most attested about Jesus is the brutal way in which he died. Anything that makes sense of how he died is probably historical. Back in grade school I wondered why, if Jesus was as good as everybody said, somebody nailed him to a cross.

But if you consider that Jesus rode into the capital city at the most sensitive time of the year, allowed himself to be received like royalty under the noses of the Roman occupiers, and promptly trashed the holiest building in the country in front of the religious leaders, it gives you the backstory on why he didn’t last a week.

Anybody who thinks the gospels are unsubstantiated fairy tales hasn’t looked at them very closely. Through the critical lens of scholarship, the events they recount seem not only plausible but quite likely.

This article appeared in the October 2010 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 75, No. 10, pages 44-46).

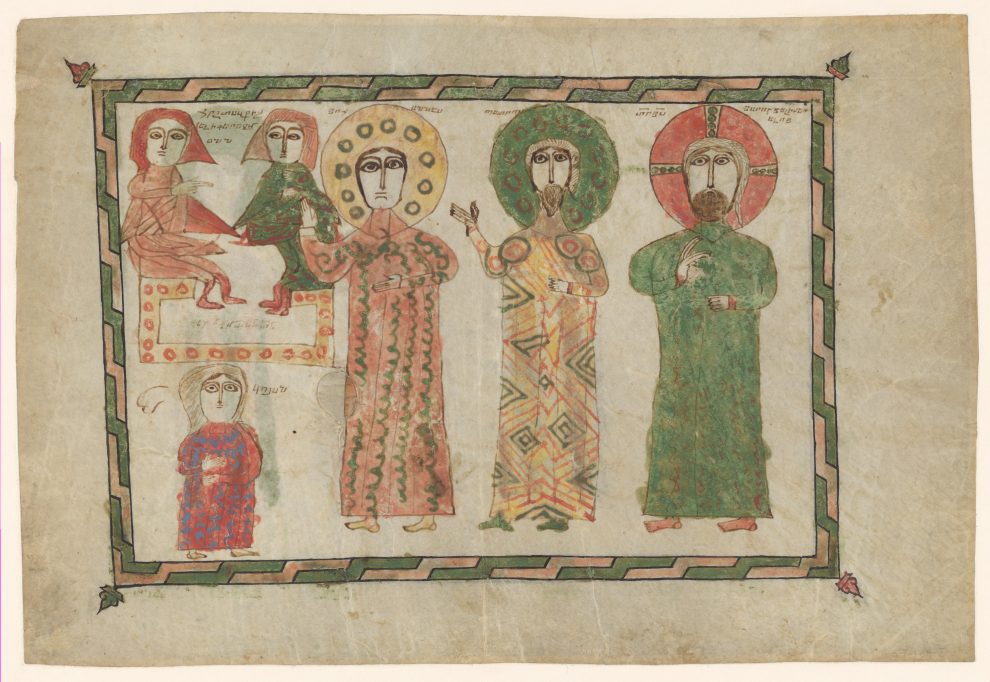

Image: Metropolitan Museum

Add comment