An attorney and charter member of the National Review Board sizes up the U.S. church’s progress on sex abuse over the last 10 years.

[Read more from Nicholas Cafardi on the importance of lay review boards.]

Nicholas Cafardi, then dean of Duquesne Law School in Pittsburgh, got a call one day back in 2002 at the height of the sex abuse crisis. Bishop Wilton Gregory, president of the U.S. bishops’ conference, was asking Cafardi to serve on the new National Review Board, charged with helping the bishops police themselves on the issue.

Gregory earns high praise from Cafardi: “He was really committed, and I think still today he probably doesn’t get enough credit for really getting the church out of a big jam.”

Cafardi went on to chair the Review Board in 2004 and 2005. His experience included years of sleepless nights and, to his dismay, being disparaged by certain prominent bishops. “I don’t think to this day they appreciate the fact that the very first review board—the 12 of us—got the bishops out of a huge hole they had dug for themselves. They now have credibility on the issue that they didn’t have in 2002.”

He will never forget the testimony of the parents of a young man who had been raped multiple times by his parish priest. One of the board members said, “I hope your son is all right now.” The mother replied, “He killed himself last year.”

“That’s a dark night of the soul, when you hear all those things done by priests and confront the failures of the bishops,” says Cafardi. “It does make you question the core of your faith. But it’s my church. There is nowhere else I would go.”

How did you end up on the first National Review Board back in 2002?

I had been the in-house counsel for the Diocese of Pittsburgh for 13 years. Let me reach around and pat myself on the back here—Pittsburgh has a phenomenal record in the area of sexual abuse. We did not put abusers back in ministry.

I was also the dean of Duquesne Law School, which, for some reason, gives you extra credibility. I was probably also one of the very few lay canon lawyers in the United States. I guess all those things added up.

What did you do right in Pittsburgh that other dioceses did not do?

Any lawyer knows that once you have a dog that’s known to bite, you’ve got to keep the dog chained. It’s a simple principle of negligence. If you know that somebody’s a danger to others, and you allow that person to stay in place and then they go on to harm others, that’s negligence on your part. It’s an unacceptable risk.

I think the Pittsburgh diocese was lucky in that they had in-house counsel. My office was inside the chancery, so I didn’t have to wait for a phone call asking whether something was a problem.

It was my consistent legal advice that we could not put these men back in ministry. I worked with Bishops Vince Leonard, Anthony Bevilacqua, and Donald Wuerl, who was, I think, one of the very first bishops in the country to go out and meet with victims and literally sit down with them at their family tables. He told me how much it changed him. He deserves a lot of credit for that. At that time, in the late 1980s, many bishops were not dealing with victims directly.

You impressed upon the bishops of Pittsburgh that keeping accused priests in ministry was an unacceptable risk. Didn’t that thought occur to bishops in other dioceses?

I don’t think they were involving their attorneys as early as Pittsburgh did. And not only am I a layman, but I’m also a parent. I was really lucky in that my wife was a pediatrician at Holy Family Institute in Pittsburgh, which deals with mostly court-assigned youngsters, many of whom have been abused.

My wife let me know very early on that the effects of sexual abuse are lifetime injuries, something these kids would deal with for the rest of their lives.

So I’m a parent. I have this knowledge from my wife. As a result, I had strong views and I was listened to. But I was also involved from the very start.

Did bishops look at sex abuse through the lens of sinfulness rather than law and negligence?

I think most bishops saw it as a sin, and sin in our church gets forgiven. Other aspects weren’t always part of the analysis.

When the National Review Board saw the reports from other dioceses, we learned that a priest accused of abuse would come in and tell the bishop, “I’m sorry, it’ll never happen again.” And since we are a church that believes in forgiveness and redemption, that sometimes carried the day.

In the early days a priest-abuser got sent away for a 30-day retreat; then he would be back on the job in another part of the diocese where nobody knew him.

At least later on they started sending them to treatment. So even though I criticize the therapeutic approach, and rightly I think, it actually was an improvement on what had been done before.

Didn’t the bishops at some point realize the magnitude of the problem?

Before the 1984 case of Father Gilbert Gauthe broke in Lafayette, Louisiana, the bishops weren’t talking to each other about their abuse cases. That was really the first sex abuse case that received major media attention.

The review board decided we needed to know the numbers from every diocese, to know how big the problem was.

It was certainly big. Our 2004 report says 4 percent; I think the later numbers have made it more like 6 percent of all priests in the U.S. And more than 10,000 victims in this country. Granted, that covers the period from 1950 to 2002.

I don’t think the bishops, at least initially, appreciated how nationwide the problem was. And we now realize it’s a worldwide problem.

I think Rome originally saw this as an American problem: This was something about us Anglo-Saxons, that we overreact to sexual issues.

As a matter of fact, it was about Anglo-Saxons, but not in the way they thought. Anglo-Saxon—really Anglo-American—law is different from the civil law of Europe. It is very difficult in Europe to sue somebody for a wrongful act.

It is no accident that this crisis broke in the common law countries—America, Canada, Australia, Ireland—because in our courts you can sue people when they harm you. So yes, it did manifest itself in America first. Not because of our sexual prudery, but because our legal system enabled these guys to be sued.

In 2002 the U.S. bishops adopted the Charter for the Protection of Children and Young People as well as a set of norms to guide their behavior. What does the charter itself actually impose?

The charter itself is not law. It is simply an agreement among the bishops saying: Here are the things we will together do. The National Review Board has the ability to oversee the promises the bishops have made in the charter, and, if they see them being broken, to say something.

But the norms are canon law. The charter and the norms tend to parallel each other.

The important parts of the norms are the obligation to report to civil authorities as soon as you know about an accusation; the requirement that you have to deal with investigations immediately; and if the investigation shows credible basis for belief, the priest has to be removed from ministry. Most importantly, once guilt is established, the abuser may not return to ministry. Ever.

Must a priest guilty of abuse be laicized?

No, the norms don’t require that. They offer two alternatives: Either a penal process in which the result would be laicization, or a life of prayer and penance. The latter is what they’ve been doing for many older priests who abused when they were much younger. Almost as a matter of charity, they’re allowed to remain priests. They’re supposedly monitored so they’re not having contact with children. They just say their daily private Mass, and they get their retired priest’s stipend.

Aren’t there diverging opinions about whether abuser priests should be forced out of the priesthood?

The opponents of laicization say, “Once these guys are out of the priesthood nobody’s watching them. On their own they could do more harm, whereas if they’re in the church living a life of prayer and penance, at least they’re monitored.”

The problem is that the church is not good at monitoring people or running a prison system for priest abusers. Yet today most dioceses have a place where these guys are living, sort of a prison if you will. Most American Catholics don’t even know that. But what’s the alternative? Turn them loose on society? This is as close as I can see to a no-win situation.

I have been accused of being too harsh on these guys. But our theology says that a priest functions as an icon of Christ. If through his sexual abuse of a child he has so disfigured the Christ icon, I don’t see how you get that back. If you lose the ability to be an icon of Christ through something you’ve done, then I don’t see how you haven’t also lost the ability to function as a priest.

That’s a hard line. As I said, I’m a father. I have a wife who’s a pediatrician and who saw the effects of child sexual abuse on a regular basis.

Can you think of ways in which the Dallas charter or the norms didn’t go far enough?

The norms only covered priests who abused; there is nothing in there about bishops. That was always what was missing from the Dallas norms and the charter.

The crisis was a double crisis. The worst part was the great harm that individual priests did to youngsters. But the second crisis was about the bishops who knowingly allowed these men to remain in ministry and therefore enabled their subsequent abuse.

The Dallas norms deal effectively with priests in ministry who abuse. There is nothing in the Dallas norms about the bishops who enabled that to happen.

Was it ever on the table?

The National Review Board mentioned in our 2004 report that there needed to be a way to hold these bishops accountable, because they have immense authority. But authority without accountability is tyranny. That’s in the report. Bishops should be accountable to their people, to their priests. Right now there’s no mechanism for that kind of accountability.

They are accountable to the Holy See, and there are mechanisms there, but they don’t get used.

What are some of the good things that have happened since 2002?

The good thing is that most dioceses are following the norms and, as a result, much to the church’s credit in the United States, I do think the problem is under control. That’s why it’s so distressing that we have these eruptions, such as in Philadelphia and Kansas City, where you realize bishops were not following the rules. These come across as eruptions because other people are following the rules.

Also don’t forget, the norms need to be renewed every so often. They’re not perpetual law. So there is no guarantee that 10 years from now the norms will still be there. I would see any bishops wanting to get out from underneath the norms as a real sign of bad faith. We need the norms to be there for the foreseeable future.

Why would bishops, such as those you mentioned in Philadelphia and Kansas City, ignore the norms?

I don’t know what was inside their heads. Obviously they thought they knew better than the rest of the American church.

Yet you said that the norms have the force of canon law in the United States.

Yes, they do. But bishops violate canon law all the time.

They do?

Every time a bishop turns around, he bumps into canon law. If anybody’s likely to violate it, it’s a bishop because it governs almost everything he does.

Is there something that gives them the authority to bend the law?

No. This is criminal law. You can’t dispense from it. They were bound to follow it, but they chose not to. Evidently Bishop Finn in Kansas City chose not to.

Here in Chicago, Cardinal Francis George kept Father Daniel McCormack in ministry after he had received information indicating he was an abuser and despite his own review board advising him to remove the priest. In the period between the time that George knew and the time McCormack was arrested, there were more victims. The next year, 2007, George was elected president of the U.S. bishops’ conference.

What does that say about bishops and their attitudes toward the norms?

In the dioceses where the norms are being followed, there haven’t been any additional problems. And if you look at the number of incidents, they have come down precipitously. We have to keep in mind, however, that there’s a reporting lag in cases of sex abuse.

Why does a bishop choose not to follow the law? I don’t know what goes on in their consciences when they make those kinds of decisions, but I’m sure they find some way to justify it. These aren’t bad men. These aren’t evil guys. They must see some kind of greater good, but what that greater good could be eludes me.

If most bishops are following the norms, how can the church hold accountable those bishops who choose not to follow them?

That’s a really good question. We’re not holding bishops accountable for these kinds of things. We’re good at holding bishops accountable for heresy. I mean, a bishop in Australia says we should talk about women priests and he’s no longer a bishop.

So we’re good at holding bishops accountable for going off the reservation in terms of church discipline in that sense. But we’re not good at holding bishops accountable for failing to follow their own laws.

And by the way there is a canon, criminal canon 1389, that says if you hold an office in the church and, through your acts or your omissions, you cause injury to another, that’s a crime. To my knowledge no bishop has been called up on 1389 charges yet. Of course, the Holy See would have to do the calling. It doesn’t happen.

Has there been any discussion of actually calling certain bishops to account?

The only way they’re being held to account right now is civilly. They are not being held to account inside the church.

Is it a problem in canon law?

No. The Dallas norms are canon law for the United States and not following them is a violation of our law. I could certainly envision someone from the Vatican coming to talk to a bishop and saying, “We think you should resign for violating the Dallas norms.”

Why aren’t bishops turning to the ones who aren’t following the norms and saying, “You need to get with the program on this”?

I’m told that there is fraternal correction, but that it occurs in private, that we just don’t know about it.

Do you think it’s helping?

Well, the vast majority of dioceses are keeping the rules. Maybe it is helping.

I don’t know if any bishops called those bishops not observing the norms and said, “You’re making us all look bad.” I hope somebody did. I’m told that it’s just not “bishoply” to talk about your fellow bishops in public.

Our bishops have no trouble speaking out politically, have no trouble saying such and such a Catholic, even if he’s not from their diocese, shouldn’t come to communion. They can speak out publicly when they want to, but they don’t speak out publicly about individual bishops who aren’t keeping the rules related to sex abuse.

Remember that our bishops today typically do not know their people. They’ve been parachuted in from headquarters. Their loyalty is to headquarters. Unless they’re getting cues from Rome, don’t expect them to do very much.

What is Rome saying?

Rome sends mixed signals on this. Four of the Irish bishops involved in that scandal resigned, but Rome accepted the resignations of only two of them. They still haven’t explained that decision.

Rome last year sent Bishop Robert Vasa of Baker, Oregon to head up a larger diocese, which is startling when you consider that Baker has been one of two dioceses—the other is Lincoln, Nebraska—that have purposely chosen not to take part in the annual audits conducted under the charter. What message does that send to the U.S. bishops?

If the church fails to keep its own rules and doesn’t police itself and we end up hurting people, we can expect the larger civil society to come in and police us. So we’re better off keeping our own rules. Sexual abuse of a child by a cleric has been a crime in the church dating all the way back to the Didache, an early Christian writing from about 110 A.D.

It also seems to me that if we’re really serious about religious freedom, we have seen real breaches of religious freedom as a result of this clergy sex abuse crisis. We have, at least to my knowledge, three dioceses—Manchester, New Hampshire; Phoenix; and now Kansas City—where civil authorities—the state’s attorneys—have been given some level of supervisory power over the diocese. I cannot think of a greater loss of religious freedom than that. And that’s a self-inflicted wound, due to a failing of the bishops in those dioceses.

I don’t recall the U.S. bishops’ conference giving a statement saying that this is an intrusion upon our religious liberties.

Do you think we have reason to hope that things will continue to get better?

Of course. We still have the Spirit guiding us. Sometimes it appears to be a tortuous path, but that’s Christ’s promise, right? He sent the Spirit to stay with us.

I actually think 10 years later, things are much better than they were. What troubles me is that not everybody has got it yet. And you have to unpack that. When you say they haven’t got it, that means kids are still being hurt.

This article appeared in the June 2012 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 77, No. 6, pages 18-22).

Read more on from Nicholas Cafardi on the importance of lay review boards.

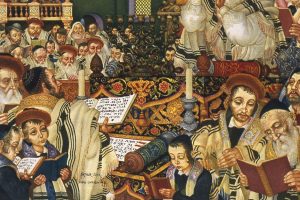

Image: Photo of Nicholas Cafardi by Tom Wright

Add comment