Is there really only one way to make a Catholic household?

Is there really only one way to make a Catholic household?

Early in June, just as the U.S. Senate was debating a constitutional amendment banning same-sex marriage, the Pontifical Council on the Family issued a document that in no uncertain terms rejected that and more. “Family and Human Procreation” not only lamented “gay couples [who] claim for themselves the same rights as those that are specific to husband and wife, [even] the right to adopt” but also heterosexual couples “willingly made sterile” by having only one or two children.

Behind the nuclear issues of same-sex marriage and adoption, however, is a larger, more complicated question: Just what is a family? The Vatican and the U.S. bishops of late have defined it quite simply as marriage between a man and a woman, which Pope Benedict XVI praised in his first encyclical, Deus caritas est, as “the very epitome of love [such that] all other kinds of love immediately seem to fade in comparison.” Although I wouldn’t want to take anything away from the holiness and importance of marriage, I wonder if in our desire to defend it as an institution we aren’t overlooking some resources our tradition can offer us as we struggle with these difficult issues.

Indeed, from the very beginning Christianity proposed a new kind of family, God’s “household,” that went beyond biology and ethnicity, one that included not only married couples and their children but others as well. Jesus himself, the gospels imply, was unmarried, and he gathered as disciples both married and unmarried men and women. Soon after Pentecost the early church joined both Jews and Greeks in one household (though not without difficulty) in which all was shared in common.

For some early Christians the traditional Greco-Roman household headed by the paterfamilias was replaced either with a form of common desert life, in which the abbas and ammas were spiritual directors rather than biological parents, or with outright isolation. The medieval church saw an explosion of new “families”: the monastic movement of St. Benedict and St. Scholastica; the mendicant groups of St. Francis and St. Clare; the Beguine women’s communities of the late Middle Ages; the social service orders of the modern period. These religious refer to themselves still today as “sisters” and “brothers” not because they are biologically related but because they share a common commitment and mission.

Indeed, as we well know, marriage was judged a lesser path than celibacy for most of church history. Pope Benedict’s spiritual father, St. Augustine of Hippo, considered marriage a mere remedy for sexual desire and would probably be a little surprised to see marriage’s glorious, if appropriate, rehabilitation as the “epitome of love.”

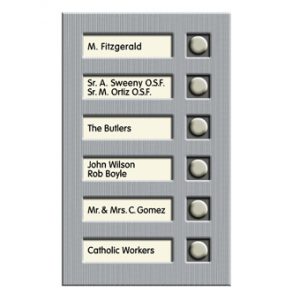

Our own age, too, has seen new Catholic families created. Catholic Workers forge family ties with the poor by sharing their lives; the communities of L’Arche create households of developmentally disabled people and their “assistants.” The growing church movements often gather as one family married couples, single people, and vowed celibates.

Parishes–church households usually headed by a celibate man–are the most obvious places where “family” in all its diversity is on display. Gathered together are nuclear families, of course, but there are also widows and widowers, singles of all ages, religious, single parents and their children, children raised by relatives, families created by adoption, and, yes, some households headed by same-sex couples and individual lesbian and gay people. And I think it safe to say that this variety is part of what makes us Catholic, though it’s not always easy.

The challenges outlined by the Vatican document on family aren’t going away, of course, and the fall U.S. congressional elections are not likely to bring out the best in us when it comes to this issue. And there’s no doubt that the mixture of sex, birth control, and the new technologies of procreation complicate matters more than a little.

But our Catholic tradition has more to offer than a one-size-fits-all approach to what a family is, and the many kinds of families that make up God’s household deserve their rightful place in our assembly. Perhaps Jesus’ own description of his family might guide us on the difficult road ahead: “Who are my mother and my brothers?… Here are my mother and my brothers! Whoever does the will of God is my brother and sister and mother” (Mark 3:33-35).

This article appeared in the September 2006 issue of U.S.Catholic magazine.

Add comment