The service begins with a Prayer to the Four Directions.

“Great Spirit who comes out of the East . . . we are thankful for the light of the rising sun. . . . We turn to the South, thankful for sending us warm and soothing winds. . . . Great Life-giving Spirit, we face West, the direction of sundown. . . . Great Spirit of Love, come to us with the power of the North, make us courageous when the cold winds of life fall upon us. . . .”

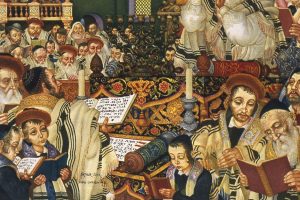

Brightly colored string dream catchers—symbols of protection—hang from the walls to mark each of the four directions. Standing before an altar, Jody Roy, a member of the Whitefish Lake First Nation, sets fire to a bowl of sage. Clasping an eagle feather, one by one people in the pews draw the smoke over their heads and chests as part of a “smudging ceremony” to cleanse the mind and heart.

“In the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit,” the presiding priest intones as the smoke disappears.

Welcome to Sunday Mass at the St. Kateri Center on Chicago’s North Side, held in the chapel of a former convent. Formerly called the Anawim Center, the center is now named for Kateri Tekakwitha, the young Algonquin-Mohawk woman who preached the gospel alongside missionaries in the 1600s and who is the church’s only Native American saint.

Like a growing number of Native Americans across the country, those who attend the twice monthly Masses here are seeking ways to combine their Catholic beliefs with indigenous traditions and rituals. Roy calls the St. Kateri Center a “place for prayer and healing, a bridge of reconciliation between Native Americans and the Catholic Church.”

Kevin Diver is one of the teens who attends the Masses here regularly. Descended from the Chippewa, the Diver family has a story familiar to many indigenous people.

Diver’s grandparents grew up on a reservation in South Dakota. His grandfather attended a Catholic-run boarding school. Lured by the prospect of better work, his family eventually moved to Cleveland. His grandparents joined a parish there, more to make social connections than out of any deep desire to practice the faith, Diver says. Still, they raised Diver’s father as a Catholic. Now Diver attends a Jesuit-run academy in the Chicago suburbs. The 15-year-old is the only Native American in the school. He says he was looking for a way to “live out my Catholic faith in the real world and incorporate my Native life with my Catholic life.”

At the center, Diver can learn about Native American concepts of leadership in a course designed for teens and study native languages.

Services that bring together both Catholic and Native American spiritual traditions are essential, says Peter Powell. An Episcopal priest, Powell has written seven volumes on the Cheyenne tribe and spent more than a half century ministering to Native Americans. “The church has a duty to preserve the culture of indigenous peoples, because God is revealed in each unique culture,” Powell says.

That was not always the prevailing view. The history of Native American Catholics is both complicated and sad, filled with frequent missteps. In the 19th and early 20th century, the federal government forced many children living on reservations to attend church-run boarding schools. Students were forbidden in many cases to speak their native tongue or practice indigenous rituals. Many were pressured to convert. Some suffered physical and sexual abuse.

Roy, the Kateri Center’s director, says one of her uncles was beaten repeatedly at his school and refused to enter a Catholic church for the rest of his life except to attend a family member’s wedding or funeral.

Franciscan Sister Marie Therese Archambault, a member of the Lakota Sioux, says the story of indigenous Catholics is one of paradox: “As a native Catholic, the very faith you embrace is one that was used to destroy you. . . . This is the terrible irony of being Native American and Catholic.”

Shadows of that history still linger. Two years ago, the Jesuit order returned 525 acres of land on the Rosebud Reservation in South Dakota to the Sioux. The Jesuits had taken control of the land in the 1880s. “I think it is an important gesture on our part that says we’re out of the property business, and we’re out of a colonial approach to the work of mission,” Jesuit Father John Hatcher said when announcing the move.

Earlier this year, a group of students from Covington Catholic High School in Kentucky attending the March for Life in Washington sparked a nationwide controversy when a video appeared to show some of them mocking a Native American elder chanting and playing a drum near the Lincoln Memorial. The students later denied disrespecting the elder and said they were responding to taunts hurled against them by a separate group.

Most Native American Catholics still worship within predominantly white or Hispanic parishes. They remain “a population invisible in many dioceses,” according to a 2003 study by the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, titled “Native American Catholics at the Millennium.”

Census experts say it is difficult to obtain an accurate count of Native Americans because many have mixed ancestry. The 2003 bishops’ study estimates that indigenous people account for about 17 percent of America’s approximately 70 million Catholics but cautions that percentage could either be overstated or too low. The largest concentration of Native American Catholics lives in the Southwest and West.

The bishops’ study also identifies issues that remain pressing today, such as a lack of Native people within the church’s leadership. “Clergy and religious serving Native people are few in number and that number is an aging population with few or no replacements,” the study finds.

William Buchholtz Allison was adopted by a Lutheran family when he was 13 months old and didn’t learn that his parents were Native American—and Catholic—until he was in his 40s. He began showing up at the St. Kateri Center (then called the Anawim Center) unsure of how interested he’d be in learning more about his birth parents’ Catholic faith. “I wondered if [the Anawim Center] would try to convert me,” he says, laughing.

Instead, his Native roots began emerging in mysterious and unexpected ways. An elder whom he met at the Kateri Center offered him a traditional flute. “When she gave it to me, I said ‘I don’t know how to play this.’ She said, ‘Yes, you do.’ And as soon as I picked it up, I started to play traditional music,” Buchholtz Allison recalls. “There is such a thing as blood memory.”

Twenty-five years later, Buchholtz Allison still hasn’t converted, but he regularly attends Mass and plays the flute at the St. Kateri Center. He also performs at powwow ceremonies throughout the country. His face lights up when he tells the story of tracing his birth father’s ancestry to the same part of the country and same tribe as St. Kateri.

At an Ojibwe ceremony a few years ago, Buchholtz Allison received a personal ceremonial pipe from an elder—considered an honor in Native culture—which he smokes when he wants to send up prayers for others. In addition to his legal name, he now uses the Native name he was given, Pukinaage Makwa, which means “Conquering Bear.”

Barbara Aston, who lives in northern Idaho, manages to keep a foot planted firmly in both her faith traditions. Aston is a Benedictine Oblate—a lay associate of the Monastery of St. Gertrude in Cottonwood, Idaho. As an Oblate, she says she tries to practice the Benedictine values of listening, community, hospitality, humility, prayer, and praise in her daily life. She also serves as a “Faithkeeper” within the Wyandotte Nation, responsible for keeping alive her nation’s spiritual traditions.

“I believe in Christ and embrace my Catholic faith and its beauty. I also embrace the beauty of my native traditions,” Aston says.

Aston was raised by her parents in the First Baptist Church but says she developed a strong early bond with her grandmother, who spoke proudly of the family’s Wyandotte roots. As a student at the Jesuits’ Seattle University, Aston found herself drawn to Catholicism. She and her husband eventually converted. Another turning point came in 1999 when she attended a reburial ceremony in Ontario, Canada for the remains of some 600 of her tribal ancestors—people who originally were buried in 1649 then dug up centuries later for study by archeologists.

“That reburial was a major occurrence for me,” Aston says. “It strengthened the desire in me to know about my Wyandotte ancestors.”

Aston now says she sees many correspondences between her Native traditions and Catholic beliefs, such as the communion of saints.

“When we gather in a circle, I feel that all of my ancestors are there as well as all who are to come. There was a Haudenosaunee elder who said the spiritual world is as near to us as the thickness of a maple leaf. To me this presence corresponds with the communion of saints,” she says.

Aston also finds resonances between the Eucharistic celebration and the tribal Green Corn Ceremony—both rituals of thanksgiving. In blessing the early harvest, tribal members “give thanks for creation and for the creator and pray to be of one heart and one mind,” Aston explains, just as “Jesus instituted the Eucharist with bread and wine, uniting us together as one body, the body of Christ that excludes no one.”

Still, Aston says she had to “make peace” with what she calls “errors” the church made in its early evangelizing efforts. “Missionaries brought the gospel, but they also imposed their culture and demonized our ways rather than just sharing the gospel of love,” she says.

Aston encounters indigenous people who remain staunchly anti-Christian to this day. She urges understanding. “There are good and bad people in every faith tradition,” she says. “There are people who intentionally misuse whatever power or influence they have over others just as there are those who believe they are doing right but are misguided in their formation, understanding, or practice.”

Susan Power is a novelist who lives in Minnesota and is a member of the Standing Rock Sioux. Power says indigenous people have learned to move comfortably between cultures and religious traditions because of the diversity found within Indian tribal nations. “So it’s not uncomfortable for people to balance different ways of doing things and different traditions,” she says.

Power attended a Catholic school until the fifth grade but says she abandoned the faith for a “more personally guided relationship with a higher power in the universe.” There is much about Catholicism she says she still finds meaningful. Native traditions, she adds, offer a missing component. “I think it’s vital to preserve our spiritual traditions, which reflect a different worldview critical to the survival of the world as we know it,” Power says.

That view emerges in Power’s novel Sacred Wilderness. It is the story of a group of Mohawk people who hold tightly to their traditions despite the proselytizing efforts of Catholic missionaries, the so-called “black robes.” In the novel, a figure known as The Peacemaker at one point offers a lesson to a young Mohawk leader who is destined to become a spiritual healer. The Peacemaker offers a vision of what indigenous tribes ultimately experienced.

“A great nation will be built on your shoulders . . . but this nation will not honor your stories or even give them any credit,” Power writes. “So it will be up to you to believe in the old stories, even when the world around you says they are wrong, they are weak, they are dead. . . . That will be the time when your people will come forth with the old stories and offer them up again.”

Power says Native people are “coming forth with the old stories” today by engaging with environmental issues. Native tribes organized a highly publicized (though ultimately unsuccessful) protest against the construction of an oil pipeline under the Missouri River and have become increasingly vocal in opposing efforts to reduce clean air and water regulations.

“The good news is that Natives are on the move, idle no more. . . . We are standing up for . . . the waters, we’re standing up for the future we refuse to gamble away as if it doesn’t matter, as if it should be someone else’s story,” Power wrote in a 2017 essay titled “Native in the Twenty-First Century.”

Native Americans are also “on the move” within the church. Dioceses with large indigenous populations have begun programs to encourage those members to become lay ministers and deacons. “In some dioceses, there is widespread use of Native symbols in the liturgy,” the bishops’ study finds.

The St. Kateri Center is a ministry of St. Benedict Catholic Church in Chicago. A few times each year, Native members incorporate some of their traditions into Masses for the parish at large. The entire congregation recites the Prayer to the Four Directions, Buchholtz Allison plays traditional music on the flute, and the pounding of a Native drum replaces the ringing of bells at the consecration of the Eucharist.

Both groups have much to learn from each other, Power says. “So many of the teachings of the world religions are similar to the traditions of indigenous people. They are not at war with each other. It’s when we get into proselytizing and missionizing where people say, ‘this is the only way’ that we get into trouble,” she says.

Powell, the Episcopal priest who helped establish Chicago’s first center for indigenous people, says he hopes Native Americans “will continue to see the Catholic faith as a fulfillment of that which was given to them in their sacred stories.” The church, he adds, should be “a preserver of their Native beliefs.”

The Masses at the Kateri Center end with the singing of a hymn to St. Kateri, today the patron of not only Native Americans but also ecologists and people in exile. Its words recall the young woman’s devotion to Christ, her missionary work with the Jesuits, her battle with smallpox, and her death at the age of 24. It is the song of a woman forced to relinquish her family, tribe, and Native spiritual traditions to follow the Catholic faith. It is a choice today’s Native American Catholics say they are no longer willing to make.

This article also appears in the May 2019 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 84, No. 5, pages 28–33).

Image: Wikimedia Commons

Add comment