On election night 2016, hands full of dirty dinner dishes, I tripped over a slightly ajar cabinet door and fell hard on my left knee, my right leg overextended at an ugly angle behind me. Two friends ran in to assist me when they heard the plates clatter to the floor. They propped me up against the refrigerator, immobilized with a bag of frozen peas on my knee, while they watched the returns in the next room, and I listened in disbelief as what I’d thought was impossible happened. The phrase “adding insult to injury” comes to mind.

For months my left leg from knee to ankle was an ugly sight. More than a year later I still can’t kneel during Mass, but I’ve accepted that my country is in the hands of an unapologetic misogynist. Every time I forget and touch my knee to the ground or the kneeler I remember that night and the disbelief, confusion, and sadness that followed.

The fall in the kitchen seems more ominous in its historical context. I was physically wounded. I felt vulnerable and betrayed. The next morning I limped out to get the mail and saw my elderly neighbor shoveling her driveway. Our eyes met, and we shared a beat of defeated silence. “We gotta stick together now,” she finally called across the yard. It sounds dramatic now, but on that day and for many days after the fear was palpable and so was the feeling of solidarity.

A year and countless op-eds and think pieces later I’ve learned just how privileged our sadness was—how many women have lived in that state of fear and vulnerability every day of their lives. It took the election of someone I perceived to be a clear-cut predator to make me realize what they already knew. I should have been afraid sooner. Then I became angry.

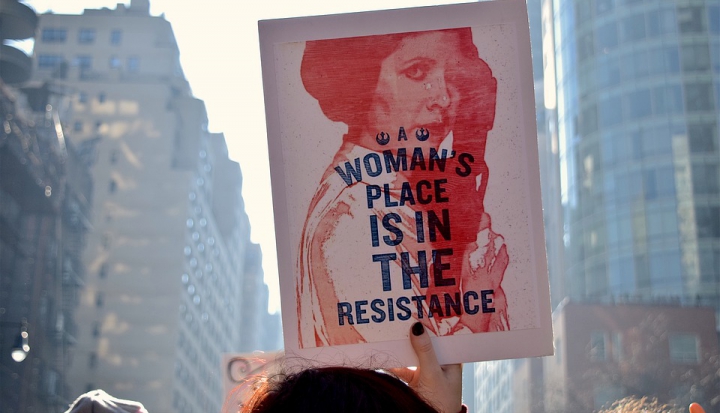

But there’s no woman so disparaged in Catholic and Christian circles—by men and women alike—as the angry feminist, the perceived man hater, the baker of “rage cookies,” as one popular columnist once described feminist writers. The angry woman is easy to mock. She has no real power. Anger makes us an even more prominent target. I told my counselor that my greatest fear was that I’d become an angry old woman. He answered that sometimes anger is the only healthy response to injustice and abuse. Sometimes anger is what keeps us, and other people, alive.

The anger of prophets, Catholic theologian Elizabeth Johnson said, leads to repentance and renewal. It has “a dangerous edge” because it threatens the powerful who benefit from systems of oppression. But it also “cuts through the despair of those who are suffering.” Righteous anger brings hope to others, not despair.

The #MeToo movement was born of the healthy anger of women who are no longer willing to remain sad and silent at someone else’s expense, who are willing to be humiliated and maligned so that someone else might have hope. For me, the trending hashtag was a second slap in the face. As I read the stories and thought about my own experiences at home, at school, at work, in the grocery store, I realized I’d been trained to accept abuse as normal and that to continue to do so was to enable the continued destruction of others.

#MeToo spun off into #ChurchToo, and women began to share stories of abuse in their communities of worship—primarily Christian. Trend trackers show women moving away from white, patriarchal Christian spirituality to embrace traditional ethnic and folk wisdom. The witches of Instagram are purveyors not just of crystals and candles but also of girl power.

As the true stories continue to pour forth, women novelists are imagining worlds where the women’s anger becomes a power that makes patriarchy a distant memory. In the alternate future of Naomi Alderman’s bestselling The Power (Little, Brown) male novelists are so rare they organize as “The Men Writers Guild.” (The ridiculousness of such a name underscores how contemporary literature remains by default the province of men.) In Kingdom of Women (Jaded Ibis Press), Rosalie Morales Kearns gathers mounting cultural anxieties about women and power within the context of a Catholic Church that has finally ordained women priests—with disastrous results.

The novel’s hero, Averil Parnell, is among the first class of ordained women, and she’s the sole survivor when the rest of her class—in a scene that is all too imaginable—is massacred. Parnell lives on, the world’s only woman Catholic priest, now a trauma survivor, possibly mentally ill or maybe a mystic or even a saint, though not a sinless one. She becomes a reluctant hero for a women’s resistance that cannily turns the massacre of the women priests into the engine for a movement that reinvents America as a matriarchy.

But Parnell resists the role they’d have her play. She is deeply ambivalent about the movement’s methods and leaders—who call the Judeo-Christian Bible a “quaint piece of tribal myth.”

Parnell still has an uneasy faith, and with her scholarship, visions, gardening obsession, and blossoming intuitive wisdom she calls to mind Hildegard of Bingen. When the movement finds a way to eradicate men completely from society, preventing the conception of male babies until patriarchy is long forgotten, she protests, urging the women to remember a time a man made them laugh or made something beautiful. But she’s dismissed as “sentimental,” her arguments based on feeling and not logic. She is, ironically, too feminine to be trusted.

Kearns, Catholic-educated from grade school through college, has a deep understanding and clear, if conflicted, love for Catholicism. Her novel isn’t a hit piece on organized religion but a deeply felt and richly imagined rendering of what the upending of patriarchy might look like in an ancient church—and what the unleashing of centuries of women’s suppressed anger might wreak in the world, beyond the embrace of folk wisdom and magic and other ways of knowing, like tarot (which plays a prominent role throughout the novel).

Though she offers no easy resolutions, Kearns ultimately concludes that the answer can’t possibly be the replacement of one violent system of oppression by another. Even if the new system is run by women.

Kearns has a downright biblical understanding of the hunger for power as the great corruptor of humanity, and it isn’t limited to one sex or gender. When the women’s resistance leaders justify their violence toward men, even men who were once known as allies, Parnell marks the irony, noting that we are, after all, “more similar than she cared to acknowledge.” Kingdom of Women explores what happens when anger that is just, healthy, hopeful—prophetic, as Elizabeth Johnson might say—tempts one to the same evil one was trying to prevent.

This article also appears in the April 2018 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 83, No. 4, pages 38–39).

Add comment