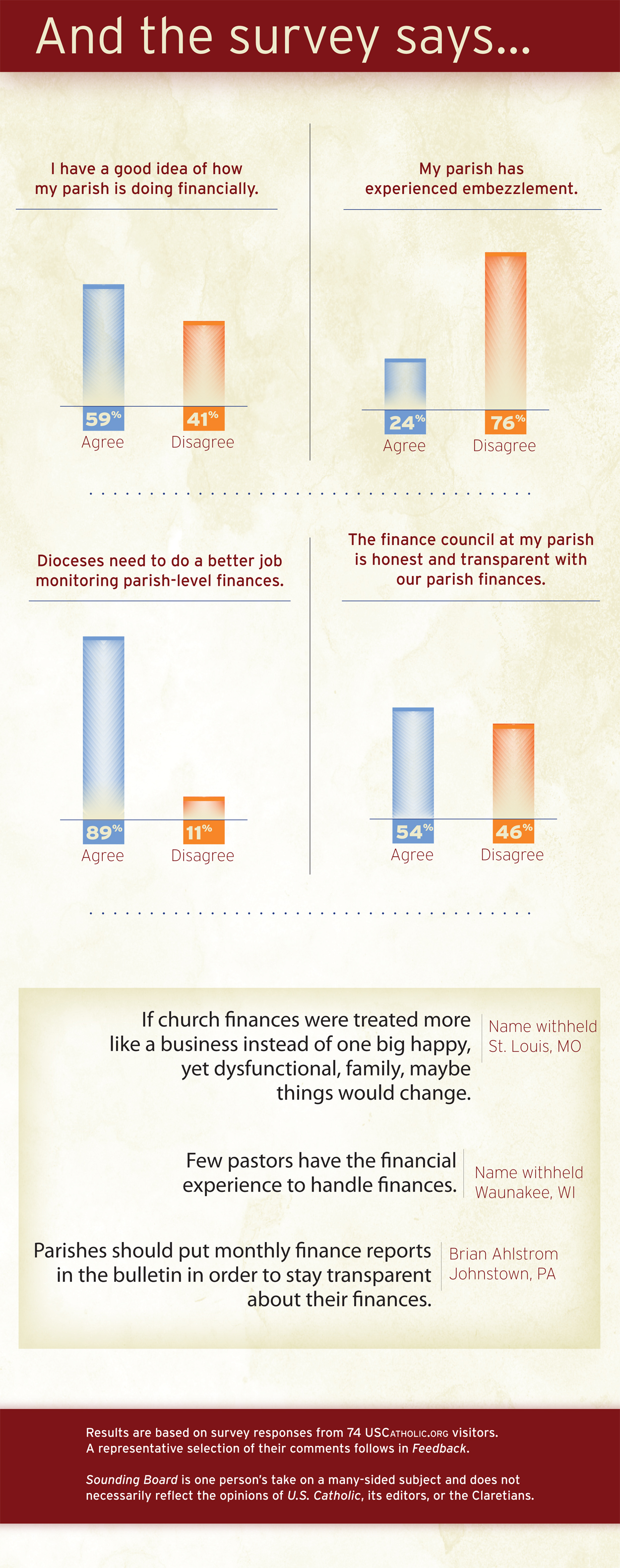

Catholic parishes and dioceses in the United States face a financial scandal: Embezzlement occurs at an alarming frequency.

In 2007 my Villanova University colleague Robert West and I conducted a study of diocesan financial practices, including incidences of embezzlement. We surveyed diocesan chief financial officers and found that 85 percent of reporting dioceses had experienced embezzlement within the last few years, many more than once.

Our study was conducted nearly 10 years ago, but the problem has not subsided. Over the last few years Catholics across the United States have been able to pick up their newspapers and read about priests and employees stealing from their parishes. Like the Michigan priest—pastor of the same parish for 30 years—who was convicted of stealing $573,000, which he used to fund risky stock market investments and his habit of alcohol abuse; the Philadelphia Archdiocese CFO who embezzled nearly a million dollars to feed her gambling habit; the New York Archdiocese employee who embezzled nearly a million dollars to purchase additions to her expensive doll collection; the Florida monsignor who was accused of stealing as much as $8 million over his 40 years as pastor, which he used to purchase real estate and take expensive vacations with his mistress; or the California mother who stole $438,000 in scrip from a Catholic school fundraising account to pay for expensive clothes and Catholic school tuition.

Embezzlers typically steal money to feed addiction or alleviate financial stress. The temptation to embezzle funds comes from a combination of need and opportunity. Are Catholic priests and parish staff more dishonest than individuals working in the private or government sectors? Probably not. Do they have more addictions? Probably not. Do they have more opportunity to steal? In most cases the answer is yes.

Catholic dioceses and parishes are notoriously careless with their internal financial controls.

The bottom line is that they’re simply too trusting. Too many parish finance councils are nothing more than rubber-stamp bodies, approving whatever the pastor or parish business manager puts in front of them. In a study I conducted, more than 40 percent of parish finance councils surveyed viewed their ability to review financial statements—from balance sheets to investment results—to be insufficient. No one thinks that a priest or layperson would steal from the church, so routine internal financial controls are either missing or lax.

To its credit, the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB) has addressed this issue. In 1995 the Committee on Budget and Finance of the USCCB (then known as the National Conference of Catholic Bishops [NCCB] and the United States Catholic Conference [USCC]) issued a document called “Diocesan Internal Controls: A Framework,” which lays out best practices for handling diocesan finances. The document also makes clear that most of its recommendations can also be applied at the parish level.

However, the document does not prevent financial mismanagement. Like other USCCB documents, it only contains recommendations, not mandates. Bishops and priests are free to follow them or not. Even when official diocesan policy is to follow the recommendations, their implementation at the parish level can be hit or miss. In my research I found that only two out of three parish finance councils followed the guidelines issued by the diocese.

So, what can parishes do to protect parishioners’ contributions and ensure the transparency of their finances?

Rotate collection-counting teams. An opportunity for theft arises when the same people count the collection week after week. It’s not unusual for a parish to have a regular team that counts the collection every Sunday. I conducted a survey that showed in 5 percent of the parishes studied, only one person counted the weekend collection. In another 40 percent of parishes, the same team counted the collection each weekend. Rotating teams of collection counters, with no team containing individuals related by blood or marriage, is the best practice for parishes.

Divide duties. Believe it or not, in some parishes, once the collection has been counted, one individual is responsible for depositing the collection, writing all of the checks, and reconciling the bank statements, usually without any checks or balances. Parishes should segment these tasks so that no one person performs all of these steps. Parish fundraisers should follow this model as well.

Limit the number of parish checking accounts. In order to control spending, parishes should limit the number of parish checking accounts. Not every parish organization needs its own checking account. Does the school need its own checking account? Yes. Does a national fraternal organization like the Knights of Columbus need its own checking account? Probably, yes. How about the choir? Probably not. A line item in the parish budget should be sufficient.

Limit the number of individuals who have check-signing authority. If parishes limit who has the authority to sign checks, they will be better able to control the disbursement of funds.

Require multiple signers for large checks. I conducted a survey that showed that in two-thirds of responding parishes only one person was authorized to sign checks, no matter how large. That gives one person too much responsibility, especially when a lot of money is involved. Parishes should require more than one signature for large checks, which for most parishes means anything over $500.

Require supporting documentation for every check. Checks should not be issued without supporting documentation, like receipts for purchases, including for those parishioners who are seeking reimbursement for an expense that they incurred on behalf of the parish. Staff and parishioners may push back on this policy if it hasn’t been required before, but hopefully once they see it is applied to everyone equally, they will become more accepting.

Use electronic transfer. Parishes should encourage parishioners to contribute money through electronic transfer, which eliminates much of the handling of cash. Through electronic transfer, parishes receive contributions even when parishioners are on vacation, sick, or otherwise unable to attend Mass. Donating electronically also makes parishioners’ weekly contributions less dependent on how much is in their checking account that week. My studies show that when a parish household starts contributing electronically, their annual contributions increase by 30 percent.

Administer audits. Dioceses should administer annual random audits of their parishes to ensure their finances are being used in the correct way. The survey of diocesan CFO’s mentioned above revealed that only 3 percent of the dioceses audited their parishes annually, while 21 percent indicated that they seldom or never audit their parishes.

Implementing better financial practices will be met with some resistance, which is why it’s important to have frequent discussions within dioceses and parishes about how these practices are intended to protect parishes and parishioners from false accusations.

One of the best defense mechanisms against embezzlement is an open, transparent, and accountable financial process. Potential embezzlers who view the system as transparent and accountable are less likely to steal. However, parishioners must insist on financial transparency and accountability at all levels, including in both parishes and dioceses. A good parish finance council is a pastor’s best friend.

Unfortunately, too many bishops and priests fail to acknowledge the importance of open and transparent finances. What they need to recognize is that parishioners will contribute more if they know how their funds are being spent.

I give presentations about proper internal financial controls to groups around the country. During my presentations I provide some examples of poor controls and their results. Inevitably I’ll be surrounded afterward by attendees who all have the same message: You think your examples were bad? Wait until I tell you about what happened in my parish!

How is your parish doing?

This article also appears in the January 2017 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 82, No. 1, pages 30–33).

Image: Flickr cc via Andrew Dyson

Add comment