Some years ago a friend underwent radiation treatments for cancer. Hair loss was to be expected, and my friend had already been bald on top for a while. Yet when he woke up the next day to find his hair shed all around him on the pillowcase, he cried inconsolably. When I saw his bare head, I cried with him—over hair, which has no feeling and no essential function. So dear are our bodies to us that we identify with every lock of hair as if it contained the very secret of us, which, on the genetic level, it does.

How do you feel about your body? If that question seems out of place for a discussion of the Bible, then it’s possible we’ve missed something. Because if ever there was a religion that respected the human body, it’s Judaism. And if ever God showed personal interest in what becomes of bodies and the people who inhabit them, it’s in the ministry of Jesus.

But before going further, I have to admit that Christianity has a bad reputation for being body-negative. I feel obliged to do a long mea culpa for the negative things that some Church Fathers wrote about the body, and that certain ascetics actually did to their bodies. I’d be willing to take a few lashes myself for dismal ideas that have been passed on by individual church representatives you may have known personally.

It’s important, however, to balance those notions with some heavy-hitting doctrines that say otherwise. Incarnation, Resurrection, Ascension, Assumption, and Eucharist are all body-affirming teachings that are central to our faith. God does not discard mortal flesh like a garment but retains and even glorifies it for eternity. When we talk about salvation, we say the whole person is saved. The body is deemed worth saving, too. Those are all staggeringly positive statements about our physical nature that must not be overlooked or contradicted.

Perhaps it will clarify matters to return to the basic biblical principles about the body that present a very different viewpoint than some of us absorbed along the way. To go all the way back to the beginning, there’s Genesis, in which God creates humanity in the divine likeness. That likeness may not refer specifically to fingers and toes, navels and earlobes, but it by no means diminishes or excludes them.

And while God declared many of the aspects of creation “good” after their conception, once humanity entered the picture, God upgraded the assessment of the world to “very good.” The bodily existence of folks like you and me is very good in the eyes of God. It seems rather shabby of us to see ourselves in any other light.

In Jewish biblical thought, the body holds a sacred character because of its origin in the hands of God, molded like a potter shapes the clay. As a holy thing—not unlike the vessels used in religious rituals—humanity had to be preserved from uncleanness, which was understood to come from outside acts or interventions. These could be passed on from sinful parents, ingested as food, or contracted by disease or sexual immorality.

Jesus later redefined uncleanness as something generated from within, originating in the intentions of the human heart. This radical reinterpretation of ritual purity caused great excitement for Jewish thinkers like St. Paul, who perceived its liberating ramifications for believers both within and outside of Judaism.

It’s interesting to note that Jesus didn’t dismiss the idea of impurity altogether. He still marched healed members of the community off to the priests for formal approval, and he acknowledged the need for the forgiveness of sins in some who were physically ailing.

But relocating sin within the human spirit rather than seeing it embedded in the flesh did change everything. Jesus touched lepers, bleeding women, and the dead without fear of religiously decreed contagion. It’s no accident that his own body and blood became a means of promoting holiness rather than one more source of impurity.

Even in a religious system with an undeveloped idea of afterlife, Hebrew culture nonetheless took great care with human remains. The burial of the dead—what the church now calls a corporal work of mercy—was long considered a mitzvah, or good deed, in Jewish custom. Because the body had its origin in God, to dishonor the flesh remained a horror even after it was lifeless.

Contrast that attitude with the behavior of nearby Assyrians, who gleefully decapitated enemies and ran their bodies through with spikes for the purpose of display, as the prophets record. Meanwhile the reverent Jew considered the burial of the bodies of strangers and even enemies an act pleasing to God. Even though contact with the dead made a person ritually unclean, it was an uncleanness worth enduring for the sake of a greater good.

We don’t have to look further than the death of Jesus to see the risks God-fearing Jews took to honor his body. Joseph of Arimathea, a member of the Sanhedrin, faced Pilate personally for permission to remove Jesus from the cross. He also donated his own family tomb for the burial. The women of Galilee are credited with returning to the tomb in order to anoint the body and to wrap it properly, although John’s gospel records that Nicodemus, a Pharisee and Sanhedrin member, had already done this. The fact that so many people took their lives into their hands to see that Jesus’ body received due honor after death testifies to the significance with which these actions were held.

That a body might be restored after death, however, was a relatively late idea in Jewish thought. In the century before Jesus’ birth, the writer of the Book of Wisdom affirmed that the souls of the just are in the hands of God in the afterlife (Wis. 3:1). But the text doesn’t go so far as to say their bodies would be preserved, too.

The writer of 2 Maccabees, however, does make this claim in the story of the seven martyred sons. As each son approaches his grisly death, he affirms his hope in resurrection. But as he surrenders his hands and tongue to the mutilation, one of the young men also bravely declares: “It was from heaven that I received these; for the sake of God’s laws I disdain them; from God I hope to receive them again” (2 Mac. 7:11). In this short profession of faith, we hear the rumblings of a theological revolution.

The Pharisees of Jesus’ generation strenuously argued for the existence of an afterlife, while Sadducees just as strongly disagreed. But the debate about what happens to the just one after death got a big boost from the Christian community’s insistence on the bodily Resurrection of Jesus. Paul put the matter simply: If Christ is not raised, our faith is in vain.

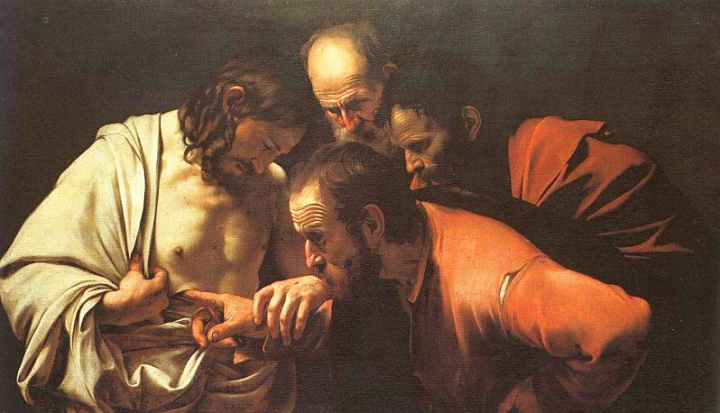

The witness of the apostles was not simply a testimony to the miracles and teachings of Jesus, but to his resurrected life first and foremost. Paul keeps a careful log of who saw Jesus with their own eyes after Easter (1 Cor. 15). The gospel writers demonstrated the physical reality of the Risen Lord by insisting that he ate and drank with his friends after death. Even his familiar wounds could be touched.

The Ascension of Jesus is a vital finish to the story of God-with-us that began with Incarnation. Jesus doesn’t just disappear like a ghost. He has to exit the scene with his body, which so uniquely operates as the intersection between heaven and earth. And Jesus leaves with us a meal of his flesh and blood that contains the seeds of our own immortality.

These bodies of ours that fill us with both wonder and shame, that carry the conflict of pleasure and pain, and register the rise and decline of our vigor, matter a great deal to the One who fashioned and redeemed them. There is indeed dignity in the tears we shed over a lock of hair or a loved one’s body as it is taken from us for the last time.

Image: cc via Wikimedia Commons

Add comment