If we want people to listen to us speak about God and faith, we also must learn the language of science.

When I was a kid, my cousin introduced me to Carl Sagan, the physicist-evangelist of the wonders of the universe. When it came to Sagan’s description of black holes and supernovae, quasars and comets, I was all ears. Never once did it occur to me that Sagan and science’s account of the cosmos being billions of years old conflicted with my growing Catholic faith.

As I grew older, I became more accustomed to the supposed “conflict” between science and religion. I am still disappointed by how the two sides so often fail to understand each other. The March debut of the remake of Sagan’s popular 1980 series Cosmos unfortunately didn’t improve things.

The opening episode told the story of Giordano Bruno, an Italian scholar and mystic who, a generation before Galileo, experienced a mystical vision of an infinite universe of planets full of life not unlike that of contemporary science, which he was eager to share with his 16th-century contemporaries.

Not surprisingly, Bruno’s mission ended at the hands of the Roman Inquisition. But while host and astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson rightly noted that Bruno suffered not because he was a scientist but for his “free thought,” I found it curious that the producers chose to profile a man who was fundamentally a mystic and theologian to fortify the science-religion divide. Bruno could just as easily serve as an example of how science and faith might arrive at the same destination by different paths.

I wish Tyson would have had other conversation partners when it came to faith—religious folk who know that Christianity can learn to speak “science.” In fact it learned long ago, when Thomas Aquinas synthesized the medieval vision of the cosmos described by Aristotle with the Christian faith. Unfortunately for Tyson and for us, contemporary Christianity often continues to speak as if Aristotle’s work still describes the world we live in—and we believers can’t blame science for that.

The trouble for believers is that Charles Darwin and Albert Einstein, among many others, have long ago destroyed the last vestiges of the static world described by Aristotle. Today we live in a world of quarks and muons, natural selection and genetic mutation. Theology has struggled to cope with this disruption, and too often Christians still imagine God as Thomas Aquinas did: an unmoved mover, a first cause, an intelligent designer. Our image of a God “up there” pulling strings needs some major alteration if we hope to continue to speak of the divine convincingly in a culture driven by science and technology.

Theologian and Franciscan Sister Ilia Delio puts it plainly in her book The Emergent Christ (Orbis): “ ‘A mistake about creation will lead to a mistake about God,’ Thomas Aquinas remarked. We need to know the book of creation today, as science informs us, to know about God.” Delio notes that, above all, we Christians are going to have to deal with our fear of change—a great constant in our evolutionary universe—if we are to imagine an “evolutionary, interrelated God,” a God who can be the source of the change woven into the universe.

Delio invokes the 20th-century Jesuit mystic, anthropologist, and theologian Pierre Teilhard de Chardin as a guide. Teilhard began imagining evolution as a way to understand God and Christ when it was still quite “dangerous”—and he nearly suffered a version of Bruno’s fate. Like Bruno, Teilhard’s vision of the cosmos and God was as much fueled by a mystical vision—by his faith and confidence in the gospel—as by the scientific method.

We also must learn to give such an account of our Christian faith—one rooted equally in prayer and in exploration of the world as we now know it—if we wish the gospel to endure into the future that awaits us. If Tyson and his colleagues need new conversation partners, it’s up to us to learn their language, as both Thomas Aquinas and Teilhard did before us.

This article appeared in the May 2014 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 79, No. 5, page 8).

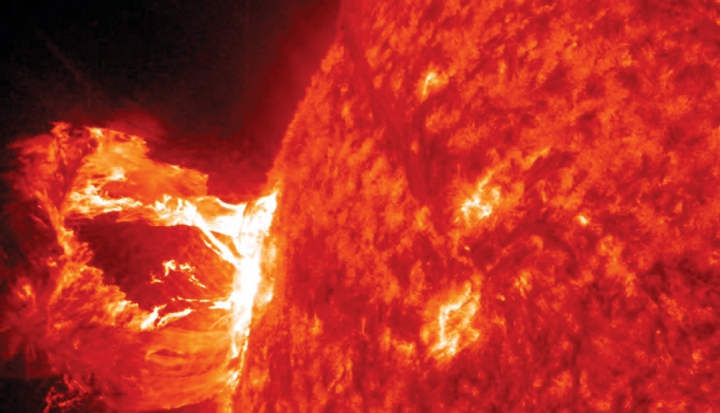

Image: Flickr photo cc by NASA

Add comment