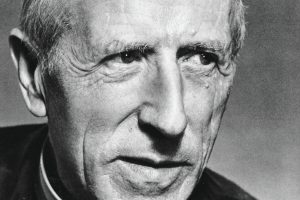

This Ugandan sister is a surrogate mom to the “Lost Girls” of her nation, restoring their sense of dignity after their years in a living nightmare.

When Sister Rosemary Nyirumbe visited the offices of U.S. Catholic recently, she described in chilling detail how she and her fellow sisters hid 500 children when Uganda’s civil war was raging–children who had run from their own villages for fear of being abducted by Joseph Kony’s Lord’s Resistance Army. “I developed a system that I would never go to sleep before midnight,” she says. “I had to keep awake because I wanted to know that the children were safe, that everybody in the compound was safe.”

Some of the children who fled to the sisters were girls who had escaped after having been kidnapped by the rebels to serve as child soldiers or sex slaves to the rebel commanders; a number had escaped with the infants and children they had borne in captivity. Many girls had tried to return home, said Nyirumbe, only to face rejection because the rebels had earlier forced them to commit atrocities in their own villages. Some had even been made to kill their own family members. This horrendous tactic had fulfilled its purpose, which according to Nyirumbe was to prevent the youngsters from ever being accepted back into their communities. “When these children started coming back, they thought they would get people welcoming them, accepting them with love, but people were scared of them, saying, ‘These children are trained killers,’” she says.

Sister Rosemary not only welcomed these girls who had somehow found her, but she took to the radio to tell any other such girls that they could find an open door at St. Monica’s in Gulu. “I said, ‘If you have nowhere to go, you come to us, we will open the door for you, we will train you.’”

Nyirumbe turned St. Monica’s, the sisters’ girls school which had lost most of its students during the civil war, into a training center for these girls and young women who had endured not only kidnapping, violence, and rape, but also now being ostracized by their own families. The school educates their children as well. The civil war ended in 2006 (although rebel leader Joseph Kony is still at large), but Sister Rosemary’s work goes on. She has taught the girls sewing, cooking, catering, and other skills which enable them to support themselves, so they must neither beg nor turn to prostitution. Every girl who completes the course at St. Monica is employed, she says proudly, many of them at top hotels in Uganda. The school’s latest project is crafting fashionable purses made of pop tops from aluminum cans, which fetch a handsome price in the United States. And Sister Rosemary is quick to note that she pays the girls for their work.

Nyirumbe points out the one bright spot in this unbearably tragic story: that the girls brought their children with them when they escaped, a testament to the survival of their maternal instinct despite the horrors they had endured. Yet the years of violence had obviously taken their toll. “The only way we could make these girls not turn their anger toward these children was accepting them, loving them, and giving them skills to say, you can love these children,” she says. “In a way we had to show them how to love their kids by loving these women and loving their children–we offered to be mothers to them, so they could care for their children.”

Nyirumbe speaks of another difficulty faced by the girls: invisibility. While many people have heard of the “Lost Boys,” former child soldiers sometimes brought to the United States for education and rehabilitation, “I have not heard the term ‘Lost Girls,’” Nyirumbe says. “Why are people not talking about the girls? Why are we not caring for them? These girls don’t have the opportunity the boys have simply because they have the scar that will follow them—and that scar is their babies, their children. These girls need support, need education. They are the future of the nation. If nothing is done for them, what has happened in the past can still be repeated—these are going to be bitter women. That is why I took up the skills training, to let society understand that these women are the greatest contributing factor to the economy of the country. They are giving hope to these kids. They are giving hope to the nation.”

Named a CNN Hero in 2007, Sister Rosemary’s work in Uganda has attracted the attention of such celebrities as Forest Whitaker, Chelsea Clinton, Adrian Peterson, and many others. She points out that while other rehabilitation exists for child soldiers, St. Monica’s and its two sister schools in Atiak, Uganda and in South Sudan are the only ones where the staff lives permanently with the young people. “We are here preaching the gospel of presence,” she says. As for the origin of her phrase “sewing hope,” now the title of a documentary film about her work? “I say, use your needle, use your hand, sew away the pain, sew away anything people will say about you. People may call you a failure, but you’re not. People may call you a rebel, but you’re not—you’re a human being.”

The new documentary film about Nyirumbe’s work, Sewing Hope, narrated by actor Forest Whitaker, is currently playing the film festival circuit and being shown during Nyirumbe’s trips to the United States.

Want to learn more about women religious from around the world? See our collection of articles for National Catholic Sisters Week.

Image: Derek Watson

Add comment