The editors interview theologian and religious education scholar Thomas Groome.

An increasingly secular culture is often blamed for the young generation’s lack of enthusiasm for religion. But is secular society truly a roadblock when it comes to raising our kids in the Catholic faith? Thomas Groome, author of Will There Be Faith? A New Vision for Educating and Growing Disciples (HarperOne, 2011), discusses the role of secularization in passing on the faith in this web-only excerpt from his interview with U.S. Catholic.

Do you think that something in our culture is working against religious faith now in a way that it wasn’t in earlier decades?

The modern democratic societies in the Northern Hemisphere seem to either have already embraced secularism or are a sure bet to embrace it soon.

But the caveat that I always make, and that many scholars like the philosopher Charles Taylor make, is that there are aspects of secularization that are very positive, even toward religious faith.

When the prime minister of Turkey stands up at the Turkish Parliament and says, “Turkey will remain a secular society,” everybody heaves a sigh of relief because it means that that Turkey is not going to become a theocracy. When Benedict XVI was in the U.S., he complimented this great American experiment of ours on how we have managed to separate church and state, and yet have remained, generally speaking, a religious culture and society in ways that many European countries have not. It looks as if our embrace of that aspect of secularization—separating church and state—was very wise.

On the other hand, some aspects of secularization have pushed religion and faith to the margins of society. I’ll give an example. When I was about 5 years old, I got pneumonia. I lived on an Irish farm, about 10 or 12 miles from the nearest doctor. My father, who was a politician, was away in Dublin for the week. The car was gone. I’d already lost a little sister to pneumonia. Sixty years ago, pneumonia in an Irish village was a very serious illness.

And my mother, Lord rest her, did what she knew how to do best. She pinned a relic of St. Theresa to my pajamas, and she knelt down beside my bed and told St. Theresa that she wasn’t leaving there until my fever broke. I fell asleep and my mother fell asleep. We both woke up and the fever had broken. My mother went to her grave swearing that that, indeed, was a miracle. And maybe it was.

The point I would make is that her granddaughters would never do that. What would they do? They’d pop the kid in the SUV and they’d be in the town in 10 minutes. The kid would be put on antibiotics and would be up and running around again in a few days. So the advances in the availability of good medical care mean, in a sense, that people don’t feel the need to pray as often as a previous generation did. Yet it would be foolhardy, and very unCatholic, to condemn the advances in medicine.

Yet isn’t some secularization directly negative in its effect on religion?

Of course. There is an Enlightenment assumption that if you become educated and sophisticated, you’ll recognize faith and religion as the superstitions of your grandparents and that you will set them aside.

That was a great bias of the whole Enlightenment movement—Marx, Hegel, Freud, Nietzsche. Then, the new atheists—Richard Dawkins and others—make it sound as if any educated, reasonable person would be well advised to set religion aside because it’s the cause of dreadful wars and evils and discriminations and oppressions, that it diminishes the human condition rather than enhances it.

So there are conditions in society that, indeed, are disposing people away from faith. In societies of 100 years ago, or even the Irish village I grew up in, to be in faith was the default position. Not to embrace your faith was terribly unusual and very countercultural.

Atheism really wasn’t an option other than for the very educated elite. Ordinary people believed in God and went to church, because the whole village believed in God and went to church. Even the thriving American parish of old, with eight priests and 25 sisters and all the rest, disposed people toward faith. Now we’ve got a society that, for many reasons, both positive and negative, disposes people contrary to faith, and so it becomes much more challenging to embrace and live a life of mature faith.

What exactly makes it more challenging?

The explosion in technology has contributed to it, the accessibility of information, of alternative views. Charles Taylor says that we now have viable alternatives to religion. There is a kind of self sufficient humanism, for example, that says you can do quite well without faith. So why would you need faith? Especially if it’s presented negatively. To try to coerce this generation into belief and into religious identity—for example, fear of hell—is definitely a losing battle. It will fail. In fact, it will turn them off and drive the people of this era away.

I also think the sins of the church have become patently obvious to everybody. It’s not as if the church has not sinned before. As Pope John Paul II pointed out at least 100 times throughout his pontificate, the church has very often failed to practice what we preach. But in the past our failures were typically confined to a particular place or time. There was no CNN following the Crusades from city to city filming what went on, whereas in our day it’s all out there. So the clergy sex abuse scandal has been a very difficult thing even for the most loyal of Catholics. We have this dreadful sense that our Catholic faith was being betrayed by many of the people whom we were expecting to epitomize it and to be the guardians of it.

That’s a dreadfully disconcerting feeling for people and can deeply shake a person’s faith. Now I always say to people, “Our faith is in God, and Jesus Christ, and the gospel, not in the church as in institution.” Yet that institution matters a great deal to us, especially as Catholics. We believe that it is to function as a sacrament of God’s reign in Jesus. When its sign effectiveness is diminished, our faith is shaken.

I also think we have to learn better ways of representing what are some of the deep traditions of our faith in ways that are more persuasive to the modern world, rather than just issuing proclamations from on high. A recent statistic indicates that 98 percent of American Catholics of childbearing age do not accept their church’s teaching on artificial means of birth control. And yet we go on shouting its condemnation from the rooftops. What good will this do? Surely it is better to bring people along than to drive them away.

There’s a whole tone, especially among our episcopacy, over the last 25 years that I think has often poorly represented the deep values of our Catholic faith.

So what should the church do?

I’m not at all advocating that we compromise what’s constitutive of our Catholic faith, the great truths that are at the top of our “hierarchy of truths,” as the Council used the phrase and the Catechism repeats it. But we’ve often taken what seems incidental to the tradition and made it sound as if this is a sine qua non to being a good Catholic, when in fact it isn’t.

Most of our disputes and conflicts are not around the divinity and humanity of Jesus, the blessed Trinity, the real presence of the risen Christ in the Eucharist, etc. Many are around more structural and political issues. Thirty million people have declared themselves former Catholics. If we’re turning away that many good people, it should surely give us some pause as to how we’re representing the tradition. We need a persuasive rather than an authoritarian apologetic for our faith; and I’m totally convinced that Catholicism is very capable of mounting a persuasive rationale for its truth claims, values, and spiritual wisdom for life—one that can convince the most “post-modern” among us.

This article is a web-only feature that accompanies Show me the way: an interview with theologian Thomas Groome which appeared in the February 2013 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 78, No. 2, pages 18-21) and Tips for raising Catholic children.

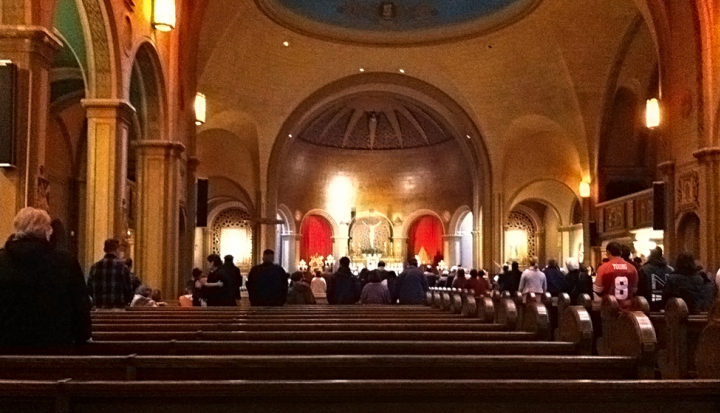

Image: Flickr photo cc by George

Add comment