The church needs to reclaim a leadership role on race in America.

It was the summer of 1954, just weeks after the U.S. Supreme Court had troubled the waters of race in America with its landmark decision in Brown v. Board of Education. A 35-year-old World War II combat veteran, a black man, knocked on the door of the rectory at Holy Family Parish in the eastern Kentucky city of Ashland.

The veteran, a Texan, had just been hired onto the staff at the local federal prison, and he wanted to speak to the pastor, Msgr. Declan Carroll, about enrolling his children in the parish school. If admitted, they would be the first black children to attend Holy Family School, and the first black children to attend school with whites anywhere in Ashland. (The public schools would not be integrated until 1960.) It also would be their first experience attending school with whites, since, it goes without saying, segregation was the law of the land in their East Texas hometown.

“I don’t see why your children shouldn’t attend our school,” the priest told the veteran. “But just to be sure, let me check with the bishop.”

A few days later, the veteran was summoned to the telephone at work. Msgr. Carroll was on the line.

“Mr. Wycliff,” the priest said, “the bishop said the Catholic schools are for all Catholic children. Your children will be welcome at our school.”

And so we were—my brother Francois, my sister Karen, and I—genuinely welcomed in the school, and our family welcomed in the parish. My mother, who still exchanges Christmas cards with some of her friends from Holy Family, recalls that on our first Sunday in the parish, Carroll met us at the front door of the church and said, “Sit anywhere you wish.”

That was important because in those days it was not uncommon in the South and the North for black Catholics to be sequestered in the back rows of otherwise all-white churches. Carroll was telling the Wycliffs that we were full members of Holy Family Parish.

It’s probably because I saw, so intimately and at such a young age, what the church at its noblest is capable of on the issue of race that I have paid close attention ever since to events at the intersection of Catholicism and race.

But there’s more to it than just my own youthful experience. I have been privileged in my now almost 62 years to meet and occasionally work with some of the lions of the Catholic interracial movement and the campaign for civil rights. I think of figures such as Theodore M. Hesburgh, C.S.C., past president of the University of Notre Dame and a charter member of the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights; the late Msgr. Jack Egan of Chicago and his indefatigable sidekick, Peggy Roach; the late John McDermott, founder of Chicago’s venerable newsletter on racial issues, The Chicago Reporter; Father George Clements, former pastor of Holy Angels Parish in Chicago; and one of my own professors at Notre Dame, John Kromkowski, longtime head of the Washington-based National Center for Urban Ethnic Affairs.

There is a long and noble Catholic tradition of advocating and working for racial peace and justice, and it deserves to be honored and preserved and extended. The work is not yet finished, and the temptations to abandon it are powerful.

“As Sen. Barack Obama campaigns as the first African American on a major party presidential ticket, nearly half of all Americans say race relations in the country are in bad shape and three in 10 acknowledge feelings of racial prejudice, according to a Washington Post/ABC News poll.”

This quote from the June 22 edition of The Washington Post suggests the dimensions of the work that remains to be done. Those three in 10 are just the ones who would admit their racial prejudice to an interviewer. How many of the rest harbor such feelings but wouldn’t admit them?

Taking up Obama’s challenge in his March 18 Philadelphia “race speech” to discuss the issue, Dawn Turner Trice, a columnist for the Chicago Tribune, created an online forum, “Exploring Race,” which she moderates.

Whites are far and away the most numerous writers to the forum, says Trice, an African American. Her dominant impression is that they are largely ignorant of other races, especially blacks. “You get the sense that they hang around in racially homogeneous groups,” Trice says.

Very often, she says, a white writer will have a question about race provoked by an encounter with a black person, perhaps a co-worker, but “they seem to have a fear of asking that person rather than asking me.”

Trice doesn’t mind serving as a sounding board. “Maybe,” she says, “this column is a place they can come and be exposed to something beyond their usual sightlines.”

But it obviously would be far preferable if people of all races could be familiar and comfortable enough with one another to satisfy their curiosities by talking frankly.

Jon Nilson, a Loyola University Chicago theologian and author of Hearing Past the Pain: Why White Catholic Theologians Need Black Theology (Paulist Press), observed in an interview in this magazine two years ago that white ignorance of blacks is an outgrowth of the racial isolation in which most whites live and which the church abets.

“[I] think residential segregation profoundly affects the nature of Catholic life at the parish level,” Nilson said. “We have many all-white parishes and therefore our most frequent ordinary Catholic experience is already giving us a distorted picture of who we are as a church in this country. I think we need to rethink the parish system, so it is not so tied to the social sin of residential segregation.”

Even within the current parish system, another Catholic institution, the school, has played an outsized role in the struggle for equal education for black children. Just as it was for my parents, the Catholic school has been the alternative of choice for black parents intent on getting a quality education for their children and unsatisfied with the public schools.

Indeed, in vast swaths of many racially isolated inner cities, Catholic schools have been the sole safe, dependable sources of elementary and secondary education, graduating a disproportionate number of the African American children who go on to successful college careers. Research by many social scientists has found that Catholic schools tend to be particularly effective in educating black boys, with whom public schools for some reason have special difficulty.

But if their quality and their instruction have been dependable, Catholic schools’ finances, and consequently their existences, are not. Each year the number of inner-city Catholic schools shrinks, under the relentless financial pressures created by ever-rising expenses and ever-diminishing contributions and subsidies to make up for what tuition does not cover.

If the church’s racial justice mission could benefit from a rethinking of the parish system, it could benefit no less from finding a way to sustain Catholic schools in areas where they are desperately needed as alternatives to what seem to be perpetually failing public school systems.

“My father came to this country when he was a teenager. Not only had he never profited from the sweat of any black man’s brow, I don’t think he had ever even seen a black man.”

So why, continued Supreme Court Associate Justice and Catholic Antonin Scalia, should his father and other relatively late-arriving immigrants to the United States have to pay, through affirmative action or, potentially, reparations, for moral debts created by antebellum slaveholders or the agents of Jim Crow?

Scalia’s has become probably the most often-quoted expression of the sentiment that Obama described in his Philadelphia speech.

“Most working- and middle-class white Americans don’t feel that they have been particularly privileged by their race,” Obama observed. “Their experience is the immigrant experience—as far as they’re concerned, no one’s handed them anything, they’ve built it from scratch.”

There’s only one problem with such notions: They’re false.

This has nothing to do with so-called “white privilege.” Rather, it has to do with the fact that none of us does it all on our own. We all, to use a worn but wonderfully expressive phrase, “stand on the shoulders” of others—family members, fellow citizens, people whose names we will never know.

Whatever horrors they may have fled and whatever wonders they might have worked after arriving here, immigrants, like the rest of us, stand on the shoulders of others.

Justice Scalia’s father may not have profited from the sweat of any black man’s or woman’s brow before he arrived in the United States. But he began to do so—and from the sweat of the brows of yellow, red, brown, and other white men and women as well—as soon as he stepped off the boat or the plane onto American soil. He became the beneficiary of the roads, streets, canals, buildings, schools, libraries, police forces, and legal systems that the men and women of this nation had put into place in the decades and centuries before his arrival. And all of these built assets enabled him to enjoy personal success and give his son the upbringing and education that led to his current prominent position in the nation’s life.

There’s nothing to be ashamed of in this. It’s the reason immigrants want to come here in the first place. It’s a major reason that most of us remain here, even when we could go elsewhere.

Yet Scalia seems to want to have things both ways. The desire to be innocent of such monstrosities as chattel slavery and Jim Crow is entirely understandable. But the notion that immigrants derived no benefit from those monstrosities and therefore ought to bear none of the responsibility for rectifying the damage is simply false.

Scalia’s argument is like that of a new investor in a company who would argue that his dividend and the price of his shares ought to be determined without reference to any debt obligations the company may have incurred before he bought into it or any liability it might have for, say, environmental pollution or other offenses.

But there’s only one class of stock in U.S.A. Inc.—common.

This desire for innocence—perhaps better, for guiltlessness—is probably the greatest of the temptations for Catholics to abandon the struggle for racial justice and equity. The temptation gains strength from being supported by so prominent a Catholic as Scalia. But in this case the justice is a false prophet.

The other great temptation might be called race fatigue.

“It’s been 44 years since the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was passed. Haven’t we paid off that debt?” “When are Jesse Jackson and Al Sharpton gonna stop ‘guilting’ us?” “What about their own self-defeating behavior—welfare queens, black-on-black crime, 70 percent of the children born out of wedlock, 50 percent dropping out of school.”

We could benefit from a lot more celebration of the nation’s racial progress than we commonly see and hear. America is in every meaningful respect a better, fairer, more just place for African Americans than it was in, say, 1954, when the Supreme Court decided the Brown case—better, fairer, and more just by many magnitudes. And anyone who doesn’t believe that cannot have been alive and aware of how vicious and capricious life in those Jim Crow days could be.

The Catholic interracial movement and Catholic participation in the broader movement for civil rights were part of the reason for this progress.

But better isn’t perfect, and America was founded on the premise that we always seek “a more perfect union.” That will require dealing with what Obama called “the brutal legacy of slavery and Jim Crow” and the distortions they wrought in the African American community. It also will require undoing the distortions that were unintended consequences of modern policies, such as a welfare system that encouraged single motherhood and the absence of fathers from their families.

And what about self-help and personal responsibility? Anyone who doubts these exist in America’s black communities cannot have visited Holy Angels, Father Clements’ old parish; or St. Sabina, Father Michael Pfleger’s; or Trinity United Church of Christ, the church built by the now-reviled Rev. Jeremiah Wright, Obama’s former pastor.

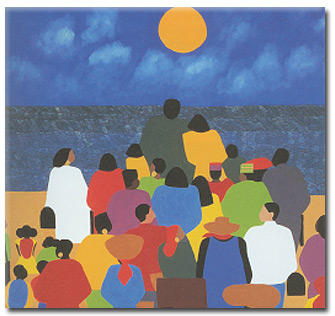

“The black church,” whether Catholic, Protestant, Islamic, or other, is the quintessential self-help institution. These congregations practice the corporal and spiritual works of mercy as assiduously as they are performed anywhere in American society. They run clinics and soup kitchens, encourage adoptions, offer job training, offer youth programs to keep young people out of trouble and headed in productive directions.

Indeed, “the black church” exemplifies about as well as any institution in American society the principle of subsidiarity, a key tenet of Catholic social teaching.

Jon Nilson’s notion of rethinking the parish system “so it is not so tied to the social sin of residential segregation” strikes me as one that deserves a lot more consideration than it apparently has gotten within the American church.

It also strikes me as the work of a generation, or even a lifetime—a perfectly ambitious project that could become the enemy of some less ambitious, merely good ones.

If ignorance of each other is the biggest current problem in race relations—and it certainly seems to be—then it ought to be possible for churches to begin addressing that without any sort of master plan.

Let white churches send a portion of their membership each Sunday to a black church, and vice versa. Let the members see how their liturgical styles differ—and match. Create a program like the Chicago Human Relations Commission’s “Chicago Dinners.” Members of black and white partner parishes could host dinners at their homes for small mixed groups, where conversation about race would be the last course. Organize multiracial encounters around readings such as Nilson’s, or John McGreevy’s Parish Boundaries (University of Chicago), or the writings of Sister Jamie Phelps, O.P. There are myriad possibilities.

If race relations remain, as Obama said, “a part of our union that we have yet to perfect,” Catholics ought to take up that challenge and turn to their church’s tradition of advocating for racial justice. That tradition is waiting to be recovered and re-energized. What’s needed is for our leaders, both clergy and lay, to seize the initiative and run with it.

Add comment